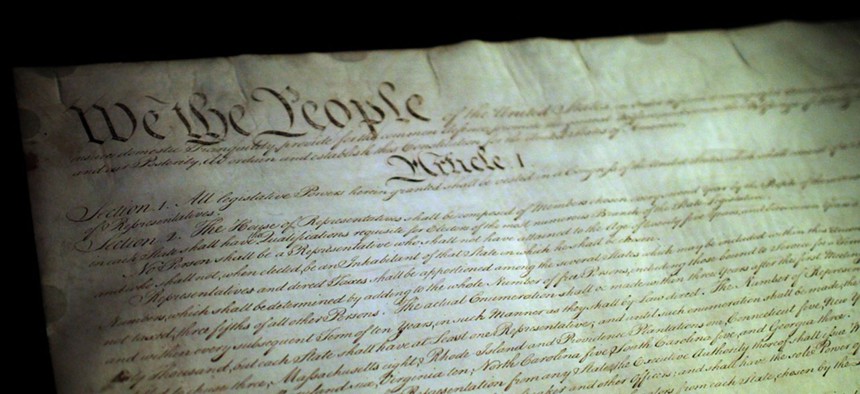

The United States Constitution is seen at the National Archives in 2010. Flickr user Mr.TinDC

Is the Constitution at Stake in This Year’s Election?

A 20-year conservative trend in the Supreme Court is on the line. A constitutional scholar examines why this issue alone will drive herds of voters to the polls in November.

If Senate Republicans are true to their word, the next president of the United States will nominate Justice Antonin Scalia’s replacement.

Given the age of several other members of the Supreme Court and rumors of others’ retirement, it is likely the next president will make as many as four nominations.

This potentially dramatic change in the makeup of the court could transform how our constitution is interpreted, an issue on which the court effectively has the last word. At stake: voting rights, how elections are conducted, requirements for abortion providers, union dues for public employees and claims to religious exemption from anti-discrimination laws, among other issues.

The court could move dramatically to the left in the event of a Clinton victory in November, disrupting the conservative trend of the last two decades. In a little-reported speech last March in Madison, Wisconsin, Clinton made it clear she would nominate progressive justices. She has also said she would want justices committed to overruling Citizens United , the case that invalidated much of the federal regulations on election spending.

Many voters may vote for Trump solely to prevent that from happening.

A Trump victory would ensure a move further to the right. Donald Trump has said the future of the Supreme Court is at stake in this election, and has released a list of reliably conservative potential nominees.

The Republican platform, approved at the party convention on July 18, says :

“…a new Republican president will restore to the Court a strong conservative majority that will follow the text and original meaning of the Constitution and our laws.”

As a constitutional law professor for more than two decades, I have observed the ways in which court doctrine can fluctuate as one constitutional vision or another commands a majority.

It is no exaggeration to say that the future of the Supreme Court, and of our constitutional system, turns on the outcome of the November election.

Different constitutional visions

Republicans and Democrats have different visions of how our Constitution is best understood. One fundamental disagreement is about whether the meaning of the Constitution was fixed when written or whether it evolves over time. Justice Scalia said the latter view is “idiotic.” Justice Stephen Breyer, usually on the liberal side, believes in a “living constitution.”

The conservatives have held a fairly reliable if tight majority since 1990. The Supreme Court started to trend in a conservative direction with President Richard Nixon’s appointment of William Rehnquist and Lewis Powell in 1972. It was consolidated by President George H. W. Bush’s replacement of Thurgood Marshall with Clarence Thomas in 1990. Replacing the archconservative Antonin Scalia with almost any Democratic nominee is anathema to Republicans, as it would shift the balance of power to the liberal bloc.

Any nominee of a Democratic president will be far more liberal than was Justice Scalia. Merrick Garland, President Obama’s nominee whom the Republican leadership in the Senate has decided to ignore , is more likely to join the liberal bloc on the court. A Clinton nominee is likely to be even more reliably progressive.

On the other hand, if Donald Trump defers to the Federalist Society when it comes to judicial appointments, as he has said he will , a Trump nominee could be expected to join the conservative bloc and, for now, preserve the ideological status quo.

Decisions that could go the other way

Many difficult constitutional questions in recent years have been answered by the court in close, usually 5-4, decisions. The conservative bloc, led by Chief Justice John Roberts, and Chief Justice William Rehnquist before him, has been dominant on many issues for more than two decades.

The conservative bloc has dominated on the relationship between the national and state governments, on the right of individuals to file suit , on the use of race in governmental decision-making , on voting rights and on the right to keep and bear arms .

Affirmative action is illustrative. Conservative textualists claim that any governmental use of race is race discrimination and violates the equal protection clause. Liberals, on the other hand, believe it is the purpose of the equal protection clause to invalidate racial classifications only when they are used to exclude (for example, denying someone service because of their race) and not those used to include (for example, taking a person’s race into account in university admissions to achieve diversity).

The court, adopting the conservative view, has held that the Constitution prohibits the government from taking race into account unless correcting its own constitutional wrongs, with the possible exception of the use of race in higher education admissions. In other words, the government may constitutionally do nothing to redress societal discrimination on the basis of race for which it is not responsible.

As Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in his opinion in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District , in which the Supreme Court rejected the consideration of a student’s race in making K-12 school assignment decisions, the “way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor rejects that abstract approach to equality as unrealistic. Dissenting in Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action , in which the court upheld the decision by Michigan voters to prohibit the consideration of race in public university admissions, she wrote :

the “way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race, and to apply the Constitution with eyes open to the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination.”

These are two very different views of how the Constitution is best understood: as colorblind, regardless of the realities of the world around us; or as permitting color consciousness, because of the realities of the world around us.

The next president, in nominating, and the Senate, in confirming the next justice, has every right to ask whether the nominee shares the originalist constitutional vision of the late Justice Scalia or the progressive constitutional vision of Justice Breyer. If Justice Scalia were to be replaced by a similar justice, little would change in the short run. But if Justice Scalia’s replacement is as different in constitutional vision as Justice Clarence Thomas was different from Thurgood Marshall, much could change.

The court, and so our constitutional doctrine, could be ideologically transformed. This is not because judges are ideologues promoting their own political preferences, but because the constitutional vision of the justices has been vetted and approved through a political process of nomination and confirmation.

![]()

This post originally appeared at The Conversation . Follow @ConversationUS on Twitter.

( Image via Flickr user Mr.TinDC )