The Dangerous Flaw in FEMA Flood Risk Maps

FEMA bases flood insurance rates on the way water behaved in the past. But the atmosphere is changing.

Hurricane Hermine made landfall in Florida last week. Some 200,000 residents have had their power knocked out, and others have been forced to evacuate due to possible storm surge of up to nine feet. Although the category-one hurricane has been downgraded to a tropical storm, the National Weather Service estimates that some Florida communities could see as much as 10 to 15 inches of precipitation by Saturday, at which point the storm will likely have moved northward to the Carolinas and Virginia, bringing with it sopping rain and the risks of more coastal flooding.

"These types of rain totals, especially when they fall in just a few hours, could lead to flooding similar to what we saw in Louisiana just a few weeks ago," one CNN meteorologist warned Thursday. That event unleashed nearly 30 inches of rain on some parts of Louisiana over three days. The unnamed storm displaced some 20,000 people and damaged twice as many homes. The American Red Cross called it the worst natural disaster since Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

“Natural disaster” is a strange term, though. Hurricanes and superstorms are fundamentally natural occurrences (notwithstanding human influence on the atmosphere), but the property damage they leave behind is not. The extent to which these events wind up as “disasters” is determined by how many people and buildings are in the wrong place at the wrong time.

In fact, with floods, the most common natural disaster in the U.S., we exacerbate the damage by paving over flood plains, trapping stormwater at a higher level than it would otherwise be. The number of people living along Florida’s shores has grown steadily over the past decade, and the population of coastal counties nationwide is projected to grow by 50 to 144 percent over the century, accompanied by more development. As the southeastern seaboard gets drenched in what is shaping up to be a very active hurricane season, it’s worth reflecting on why we do that, and why so many people choose to live in the path of storm-driven disaster in first place. A big factor in determining that?Federal flood risk maps.

Good intentions

Since 1968, FEMA has calculated and mapped flood risk for communities across the country. The agency uses these maps to set rates for its National Flood Insurance Program. Essentially, Americans who want to buy homes or build in highly flood-prone areas are mandated to buy flood insurance, which today can cost several thousand dollars per year. The idea is that when would-be buyers or builders see just how costly it is to build in certain parts of, say, Louisiana’s St. Tammany’s Parish, which has the 5th-highest number of repetitive flood-losses in the U.S., they’d avoid it—or they’d pay out the nose to settle there. People who live outside of these high-risk areas can opt to buy insurance at very reasonable rate, or not buy insurance at all.

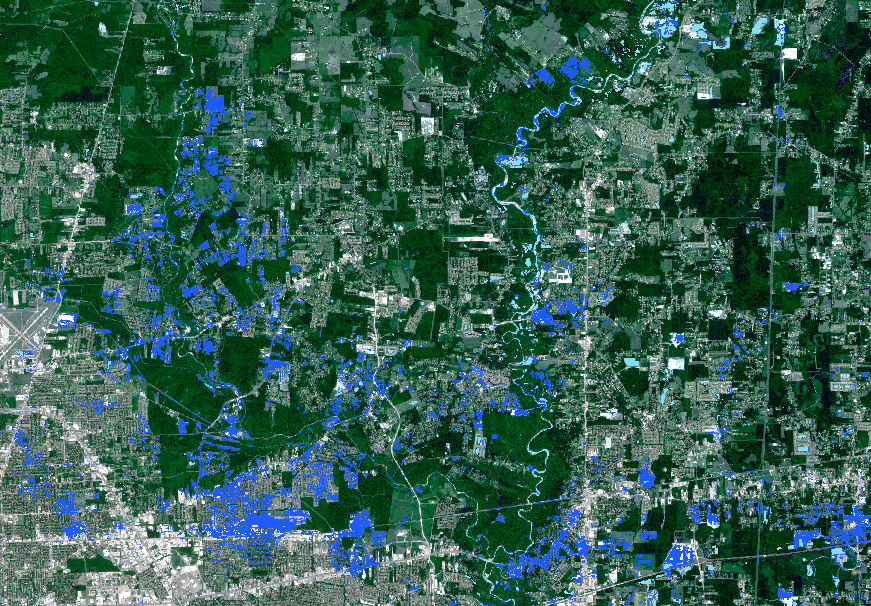

A screenshot of a map developed by UC Davis researchers that estimates the amount flooding outside of “special flood hazard areas” in Baton Rouge following August’s storms. They write, “The darker blue shows flood inundation on August 14, 2016, compared to locations that typically have water (shown in lighter blue).” (Natural Hazards Research and Mitigation Group at UC Davis)

The program is supposed to encourage people to build out of harm’s way and lower the costs of major disasters. But it hasn’t necessarily accomplished those goals: FEMA estimates that between 66 percent and 80 percent of annual flood losses, and about 25 percent of NFIP payouts, occur outside of special hazard flood zones. Nationally recognized UC Davis flood management expert Nicholas Pinter and a group of UC Davis researchers recently estimated that about one-third of the flooding that followed Louisiana’s recent floods was outside of the NFIP’s lines in the sand. And the national cost of flooding disasters is steadily rising.

Looking back to predict the future

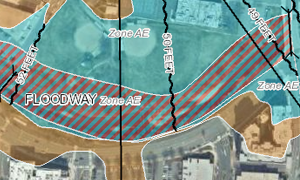

To understand why so much damage occurs outside these special lines, it helps to understand how FEMA calculates flood risk in the first place. Its standard is the “flood recurrence interval,” which is the probability of a flood occurring within a certain period of time. Swaths of land that have a 1-percent chance of flooding every 100 years—the so-called “100-year flood zone”—are designated as “special flood hazard areas.” Homebuyers and builders are required to buy insurance in such areas, because, the logic goes, there is a 26 percent chance of a flood occurring in these areas within a 30 years—the length of many mortgages. Outside of those areas are the “500-year flood zones,” other risk premium zones, and supposedly non-hazardous areas. Again, in all of these areas, flood insurance is optional.

For the uninitiated, flood recurrence intervals are often understood as forecasts. That is, if I live in a 500-year flood zone, my family won’t see a flood for another 20 generations. But that’s not correct—these intervals are probabilities, based on rainfall, river behavior, and flooding events thatalready happened. Think of it like rolling a single die: The probability of landing on four will always be one out of six, even though you could still land on that number more than once every six rolls. By the same logic, a 500-year flood could happen year after year after year. Measuring flood risk this way is like rolling dice that have sides painted with the storms of the past few centuries. It’s never going to predict the future—and if the present and future are nothing like the past, then it’s a particularly flawed way of assessing risk.

And, wouldn’t you know it, weather conditions are shifting dramatically. Climate change is heating up the atmosphere, feeding energy for storms that are more frequent and more severe. So-called 100-year events have been striking more often than they used to. The recent floods in Louisiana were caused by a 1000-year rain event—precipitation that is supposed to have a one-percent chance of occurring in a millennium. The state had already seenseveral 500-year rain events since October 2015 (and that’s to say nothing of poor Texas). If measuring risk based on past events was ever a good way to manage flood plains, it certainly isn’t now. “It’s analogous to taking a car onto the Interstate and using the rearview mirror as an indicator of what’s ahead,” says Rob Moore, a senior policy analyst with the water program at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “Climate change is a turn in the road.”

That’s not to say that the FEMA never updates its flood maps. The agency reviews the validity of tens of thousands of community maps on a five-year basis, and incorporates new technologies such as lidar and satellites for more accurate topographical data. “These flood risks use the latest science available in regards to rates,” says Rafael Lemaitre, a director of public affairs with FEMA. But at the end of the day, these calculations still rely on past weather events.

Some experts think we’d be better off it FEMA stopped drawing risk borders altogether—Pinter believes they can create a false sense of security. “We hear this again and again from flood-plain residents: They think that if they’re one inch on the ‘dry side’ or one inch higher than the flood level, they’re fine,” says Pinter. “They say ‘No one would let us build here if it wasn’t the case.’”

So they build, often without buying flood insurance, and without elevating their homes. And then those homes get washed out, with no backing or protection to help them rebuild.

Brighter days ahead?

So what should FEMA be doing to keep Americans better sheltered from storms? It so happens that the NFIP is up for reauthorization by Congress in 2017, so it’s a pretty pertinent question.

Pinter, Moore, and other experts say that a good place to start would be with President Obama’s January 2015 executive order establishing a new flood risk management standard for federal buildings. In it, the president set forth three different approaches that federal agencies can choose from to re-evaluate flood risk and promote resiliency in areas they occupy. Essentially, they can opt to move buildings several feet up and away from base flood levels, adopt the 500-year flood plain as their new standard of high flood risk, or analyze risks in a totally new way, by integrating “current and future changes in flooding” using cutting-edge climate science.

FEMA has already started to move its own construction away from flood zones by following the first two of these new standards, and it might do well to expand them to its protection of flood-prone communities. But the notion of assessing risk using the latest climate science is more problematic, Pinter warns, because that’s still an emerging field, laden with fuzzy assumptions. To his mind, it might be better for FEMA to require property owners to build to a higher water line that airs on the side of big precipitation, much like the agency is starting to do with its own buildings.

Moore also believes that FEMA should adopt standards closer in line with Obama’s executive order. But most of all, he thinks the agency needs to do more to discourage people from rebuilding in flood plains. After all, the NFIP is currently $23 billion in debt because its pay-outs far outweigh what it gathers in premiums from policy holders. Not only is the long-term solvency of the program obviously at risk, but a huge chunk of this debt covers the costs of rebuilding properties that have taken on water repeatedly. The NFIP has paid out damage claims to more than 30,000 properties that have flooded multiple times, according to the NRDC. That means the agency is effectively been helping thousands of homeowners rebuild in the same flood-prone place, over and over again.

“We need to make sure that the NFIP evolves from being a rebuilding program to a mitigation program,” Moore says. The program could do better at creating resources and incentives for states and communities to lower their flood risks independently, especially through strengthened and better enforced construction standards. Lemaitre says that FEMA is starting to take “unprecedented” action towards addressing future risk, between providing hazard mitigation funds that communities can use to buy out properties that have been repeatedly flooded, or to set up local “rainy day funds.” The agency has also been discussing the concept of a “disaster deductible,” where states would be required to spend a certain amount of money on disaster relief or mitigation before federal assistance kicks in. It’ll take approval by Congress to move this concept forward.

But the question of flood protection isn’t just a matter of better public policy. Local development interests frequently overpower the best hydrology. Indeed, many of the properties damaged in Louisiana earlier this month were very recently constructed, smack in middle of the 100-year flood plain. Some states are also much better at enforcing construction codes than others and at encouraging communities to pursue flood mitigation techniques independently. For example, twice as many communities in Illinois have more stringent building standards than in Louisiana.

And then there’s the matter of funding. Paying for the NFIP has always been a matter of contentious national debate. The Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012 summarily raised flood insurance rates for current policy holders, provoking huge backlash among lower-income Americans who felt unfairly punished for the agency’s long-standing insolvency. The new rates were quickly revoked. It might be high time for Congress to write off the NFIP’s debt and start with a clean, dry slate.

Which might be exactly what residents of America’s most flood-prone communities are hoping for as Hermine heads up the coast. It’s not that the federal government should be telling them where to live, necessarily. But it can and should do better at upholding one of its most basic duties, which is to create safety and stability in public life—rain or shine.