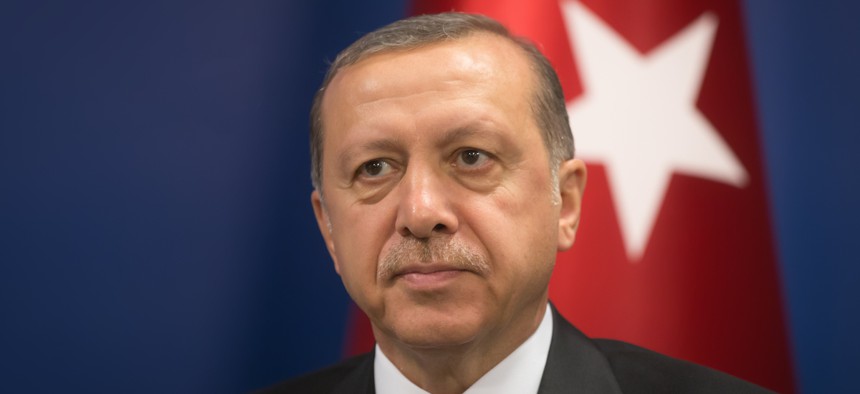

Drop of Light / Shutterstock.com

What's So Bad About Trump Calling Erdogan?

There’s a long tradition of the U.S. subordinating human-rights concerns to other interests. But there was something remarkable about the president’s move.

Just after Donald Trump grew disenchanted with Vladimir Putin, the U.S. president appeared to strike up a new fling with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Trump’s friendship with Erdogan has been budding for some time, dating back to at least last summer. But his reaction to a controversial, narrowly passed referendum in Turkey, which granted Erdogan sweeping new powers, nevertheless provoked surprise, at least to the extent that Trump’s foreign-policy moves can still shock. With international monitors citing voting irregularities, and with the opposition vowing to contest the results, Trump called his Turkish counterpart to offer congratulations. Monday evening, the White House issued a readout of that conversation:

President Donald J. Trump spoke today with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey to congratulate him on his recent referendum victory and to discuss the United States’ action in response to the Syrian regime’s use of chemical weapons on April 4th. President Trump thanked President Erdogan for supporting this action by the United States, and the leaders agreed on the importance of holding Syrian President Bashar al-Assad accountable. President Trump and President Erdogan also discussed the counter-ISIS campaign and the need to cooperate against all groups that use terrorism to achieve their ends.

Though cloaked in the drab language of official communications, Trump’s statement is remarkable for its apparent endorsement of a referendum that makes Turkey manifestly less liberal; the speed with which it was offered; the way it differs from the stated views of key American allies and even the State Department; and the lack of any expression of concern about the process.

First, there is the substance of the referendum, which pushes Turkey down the path from being a flawed but genuine democracy toward authoritarianism. “Sunday’s vote was a triumph for an illiberal form of democracy in which charismatic leaders, through democratic procedures like elections and referendums, are empowered to carry out the will of the majority of their people, largely free of democratic restraints,” my colleague Uri Friedman wrote.

Then there is the speed of Trump’s move—he called Erdogan to offer his congratulations within hours of the referendum results being made public. American leaders often wait some time after the conclusion of a vote before calling the foreign counterpart involved, and the haste is especially notable in this case because the vote is still in dispute. Erdogan won by barely more than 2.5 percent, in a result that his opponents have vowed to contest, and which independent monitors from the OSCE, of which the U.S. is a member, said was the outcome of a deeply flawed process. The State Department also diverged somewhat from the White House, issuing a statement registering concern about the OSCE observations, calling on Turkey to “protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of all its citizens,” and pointedly saying that “commitment to the rule of law and a diverse and free media remain essential.”

So Trump’s phone call, and the statement that followed it, were unusual. But how unusual? The release of the readout was met with gasps from some observers, followed by eyerolling from other quarters. The fact is that the U.S. has long made accommodation with autocrats and repressive leaders, and American presidents have for years congratulated counterparts who won election through dubious electoral processes.

“The United States gets hung up on process,” said Tamara Cofman Wittes, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and former Obama State Department official. “There’s a very strong tendency in U.S. foreign policy to acknowledge and to congratulate for holding elections, even when those elections take place in a pretty unfair context.”

There are cases where this doesn’t happen, such as when Obama didn’t congratulate Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali for winning a 2009 election widely viewed as rigged, but they are conspicuous by their absence and snubs are not unnoticed.

Moreover, there’s an obvious reason for the U.S. to be cozying up to Erdogan now, because Turkey is central to American strategy in fighting ISIS and, potentially, would be a key player in any expanded fight against the Syrian government. When the Trump administration began exploring strikes against Bashar al-Assad, Erdogan quickly said he would approve the use of Incirlik Air Base in Turkey as a departure point.

“Prioritizing near-term security cooperation over the democratic and human rights of one partner is commonplace in American foreign policy, and Trump’s action here is an exaggerated example that proves the rule,” she said.

President Obama tried for years to cultivate Erdogan as a liberal Islamist, an effort that ended in failure and in today’s increasingly authoritarian Turkey. Obama was supportive of Erdogan after a failed coup against the Turkish leader in summer 2016, but that’s not especially illuminating, since supporting an elected (if flawed) president against a military coup is clearly siding with democracy. More useful is examining the way Obama reacted to the rise of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the Egyptian president. Sisi came to power after a bloody military coup in 2013, followed by an election of dubious legitimacy: Sisi won with 97 percent of the vote. Here’s Obama’s statement:

President Obama called Egyptian President Abdelfattah al-Sisi today to congratulate him on his inauguration and to convey his commitment to working together to advance the shared interests of both countries. The President reiterated the United States’ continuing support for the political, economic, and social aspirations of the Egyptian people, and respect for their universal rights. President al-Sisi expressed appreciation for the call and welcomed U.S. support for the new government. The two leaders affirmed their commitment to the strategic partnership between the United States and Egypt and agreed to stay in touch in the weeks and months ahead.

This checks Wittes’s two boxes: It is a case of congratulating an autocrat in a flawed election, and that autocrat was an important American ally. (George W. Bush offered similar congratulations to then-President Hosni Mubarak in 2005, after Mubarak triumphed in an election in which he imprisoned his main opponent.)

“Sisi had just come to power through a bloody coup and he had presided over the massacres of thousands of people in central Cairo in one day,” said Amy Hawthorne, deputy director of the Project on Middle East Democracy, and a former State official. “That was very troubling to many of us at the time.”

There are also a couple interesting differences in Obama’s statement. First, he waited nearly two weeks after the election to call Sisi. And second, the readout shows Obama pressed Sisi, at least in part, on human-rights concerns: “The President reiterated the United States’ continuing support for the political, economic, and social aspirations of the Egyptian people, and respect for their universal rights.”

The caveat “was a mild expression of concern, but it was an expression of concern,” said Tom Malinowski, who served as assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights, and labor in the Obama administration. “[U.S. presidents] have generally, and [Obama’s] statement is in keeping, found a way to express the importance of our respect for human rights, even in a situation where a president might decide to emphasize the positive elements of a relationship for whatever reason.” In the case of the Trump call to Erdogan, “I assume the readout omitted reference to human rights because it didn’t come up on the call.” While Turkish elections have typically been considered fairly clean, Trump’s omission amid a huge political crackdown and a questionable outcome to a questionable referendum signals, at the very least, U.S. acquiescence.

It’s not just what Trump didn’t say that distresses Malinowski, but the fact that he made the phone call in the first place. Diplomatic convention dictates congratulatory calls to American allies or even frenemies (such as Vladimir Putin) after electoral wins, but there’s no convention on government referenda.

“The only thing you would be congratulating that person for is winning a substantive change to his constitution, and that’s an odd thing to do in a case where the change makes the constitution less democratic,” Malinowski said. “There have been times when we have chosen not to criticize a foreign leader for violating democratic principles. I can’t think of the last time we’ve congratulated a leader for doing that.”

Despite America’s backing of incumbent repressive leaders for reasons of perceived U.S. interests, it’s hard to think of examples where the U.S. has condoned power grabs since perhaps the 1970s and 1980s, when the U.S. propped up and sometimes assisted the formation of right-wing governments as a buffer against leftism in Latin America.

The big question, as always with Trump, is what his motivation is. Possible explanations might be boiled down to three ‘I’s: ignorance, instrumentalism, or ideology. First, Trump may simply have no interest in or awareness of Erdogan’s growing repression and the flaws in the referendum vote. Certainly, the conflicting statements by State and the White House suggest a carelessness of approach, and Trump has demonstrated his weak grasp on the facts of many foreign-policy matters over the last two weeks.

Alternatively, Trump may know exactly what he’s doing. In an interview shortly after the 2016 coup attempt, Trump praised Erdogan for putting the coup down—“I do give great credit to him for turning it around”—and dismissed worries about his repression. “I think right now when it comes to civil liberties, our country has a lot of problems, and I think it’s very hard for us to get involved in other countries when we don’t know what we are doing and we can’t see straight in our own country,” Trump said. And the president knows the importance Turkey has for American policy in the Middle East. Calling to congratulate Erdogan may have been effectively an excuse to call to talk about ISIS, Wittes said.

“This is Donald Trump! He is a deeply short-term, deeply transactional thinker when it comes to international relationships,” she said. “His concern in Turkey right now is its role in Syria and its role in the ISIS campaign. The referendum is nothing more than a distracting delay.”

Or it could be that Trump is motivated as much by his admiration for Erdogan as a strong leader, something he’s noted as far back as summer of 2016. “With Trump there is an instinctive affinity for certain types of authoritarian personalities,” Malinowski said. “By certain types, I mean the ones that strut about a lot, that use shows of macho strength to compensate for their insecurities.”

That description fits Erdogan, Putin, and Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte, among others, and Trump’s critics see worrying signs of authoritarianism in his own approach, including his secrecy, nepotism, and disregard for press freedom and an independent judiciary. The recent chill in relations between the Trump administration and the Kremlin suggests Erdogan should not count on those affections lasting. He may not care, since he has something more immediately valuable in American acquiescence to his power grab.