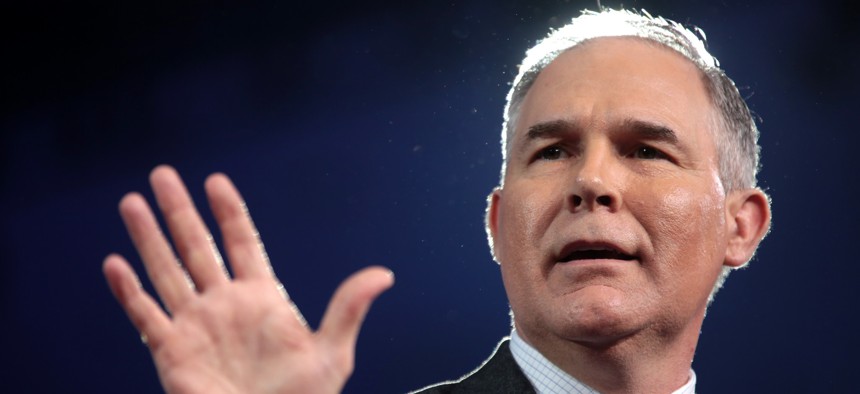

Flickr user Gage Skidmore

The Dismissed EPA Advisers Had Nothing to Do With Regulation

"It’s a very apolitical board—we never discussed politics."

Less than three years ago, the threat of an Ebola pandemic caused millions of Americans to fear for their lives.

As more than 11,000 people died of the virus in some of the poorest countries in the world—Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone—people in the United States panicked about a pandemic at home. Chris Christie ordered the forcible quarantine of any doctors or nurses returning from one of the three affected countries. This wasn’t enough, said Bill O’Reilly, who called for the cancellation of all flights from West Africa.

By one count, more than 900 segments about the virus ran on TV in the weeks before the midterm election. A majority of Americans reported that they were worried about an outbreak of Ebola in this country, something which many medical experts said was unlikely. “What’s that? You don’t want people to panic. You don’t want us to panic? How about I don’t want us to die,” said Jeanine Pirro, the Fox News host.

She was in luck. Crisis managers at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency were officially charged with making sure people didn’t die. Specifically, they had to dispose of the medical waste of people who had come into contact with the Ebola virus. Some of that waste, including vomit and excrement, can be among the most virulent vectors of the disease.

As these crisis managers worked, the underlying science of their work was informed by two scientists on the EPA’s Board of Scientific Counselors: Paula Olsiewski, a biochemist of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation; and Tammy Taylor, a research scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Both Olsiewski and Taylor are widely respected scholars of biosecurity, a discipline of microbiology and security studies that researches how to prepare and respond to both natural pandemics and biological terrorism.

On Friday, the Trump administration told them that their service was no longer needed. The EPA effectively dismissed Olsiewski, Taylor, and seven other members from its strategic scientific advisory board, as part of what many outsiders worry is a broad shift toward replacing academic researchers in the agency with industry voices.

“The EPA received hundreds of nominations to serve on the board, and we want to ensure fair consideration of all the nominees—including those nominated who may have previously served on the panel—and carry out a competitive nomination process,” said J.P. Freire, an EPA spokesman, in a statement provided to me.

“The administrator believes we should have people on this board who understand the impact of regulations on the regulated community,” Freire added to The New York Times, which first reported some of the dismissals.

Former members of the board say that second explanation doesn’t make sense. The Board of Scientific Counselors is an 18-member committee that advises the EPA on writing and organizing its strategic research action plans, the documents which guide the EPA’s Office of Research and Development. Its members are not involved in the regulatory process.

The board’s meetings—which are governed by the Federal Advisory Committee Act—are already open for the public, including industry representatives. Every meeting is also summarized online.

“It’s a very apolitical board. We never discussed politics. We never discussed regulations or proposed regulations. It’s just reacting to science outputs and giving recommendations,” said Robert Richardson, an environmental economist at Michigan State University who is among the nine members dismissed by the administration.

“Our board’s responsibility is to review science, to review the scientific outputs [of the EPA Office of Research and Development]. Posters, papers, decision support tools, things of that nature. This is completely separate from the regulatory side of the house,” he added.

Because of the breadth of the EPA’s research mandate, board members often come from a range of disciplines. In the past three years, the board has included engineers, economists, sociologists, toxicologists, chemists, climatologists, and hydrologists.

Board members usually serve two consecutive three-year terms. In early January, nine board members—who were nearing the end of their first term—were told that paperwork had been filed for them to serve a second term on the board. Through February and March, the board continued to meet and consult on research documents. Then, after the close of business hours on Friday, May 5, those nine people received an email from the EPA saying that the administration had declined to renew their appointments and that their time on the board had ended.

“This came as a surprise,” said Courtney Flint, a sociologist at Utah State University who served on the board, in an email. “I was told that the agency plans to carry out a competitive nomination process to solicit new members. No other reason was given.”

“It’s clear from the reports in the media that the current administration has said that they want to replace board positions held by academic scientists with members from industry, so I do not think I am speculating when I say that this is a political move,” she said.

But even if that is the goal, some of the laid-off board members appear to have no equivalent expert from private industry.

Paula Olsiewski, for instance, is a central figure in the field of biosecurity. For more than a decade, she ran the Sloan Foundation’s $44-million funding program in biosecurity, coordinating research across the country.

As part of her role on the Board of Scientific Counselors, she chaired the EPA’s homeland-security research subcommittee. She and Taylor also had to carry top-secret clearances so they could advise the agency’s research.

On Monday, she gave me an example of the kind of work she did for the EPA. “When bird flu hit various poultry farmers, and you’re the farmer, where do you go for advice? All these chickens and turkeys have to go somewhere after you euthanize a flock. What do you do with that waste so it doesn’t contaminate other flocks?” she said. “The EPA’s homeland-security research team figured out what to do. This is not sexy research.”

“We’re scientists reading nerdy reports, meeting with other brilliant scientists, talking about particle size or spore size,” she told me. “‘The work [we were] doing is very, very technical. This isn’t light reading. But this is very important research. What do you do with dead birds? What do you do with Ebola waste?”

Other biosecurity experts confirmed that Olsiewski has played a pivotal role in developing the field of biosecurity and that she has helped other people develop careers in the field.

“Dr. Paula Olsiewski has a unique and deep level of expertise in biosecurity,” said Megan Palmer, a senior research scholar in international security at Stanford University, in an email. “She provided support and leadership, through her programs at the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, for activities that have formed a basis for current approaches to biosecurity.”

She added that it was hard to find someone in the field who wasn’t helped or supported by Olsiewski’s programs in some way, including herself.

When I asked Olsiewski how many people had comparable experience in biosecurity, she demurred. “I would say… the country needs more people who have that experience,” she told me. “There aren’t many people who study how to manage waste after a biological incident.”

She also praised her fellow member of the board, Tammy Taylor, a longtime biosecurity researcher who could not speak to the press on account of working for the Department of Energy. Taylor was vice-chair of the agency’s homeland security committee. She was also dismissed from the board last week.

“It may be surprising that two women were leading the homeland security committee,” Olsiewski told me. “But if you were to review our resumés, you would see we’re highly skilled, with deep experience and subject-matter expertise. I’m not saying that this is gender-based, but it has been shown that science gets done best when it’s done by diverse teams.”

It is unclear where the agency will find researchers of Olsiewski’s stature to serve on the board. It’s also unclear how the study of cleaning up from biological incidents carries a significant regulatory hazard.

Even scientists who work closer to more traditional environmental policy questions say that the board’s work was always far removed from regulatory work. “The research takes place, and you hope there’s someone at the top asking, ‘What have we learned from the science, so that it can shape policy?’ But we didn’t discuss that [on the board], and it’s outside of our purview,” said Richardson.

“Doing something like this has no practical effect on regulatory reform, but it may send some message to the administration’s base that, ‘We’re getting rid of these scientists,” he added.

The Board of Scientific Counselors is not the same organization as the EPA Science Advisory Board, which advises the administrator and the agency’s rule making process. That board is a favorite target of Republicans in Congress. In February, Congressman Lamar Smith of Texas said that its members were “nothing more than rubber stamps who approve all of the E.P.A.’s regulations.”

“The E.P.A. routinely stacks this board with friendly scientists who receive millions of dollars in grants from the federal government. The conflict of interest here is clear,” he added.

(Image via Flickr user Gage Skidmore)