Defense Department file photo

Navy Poised to Fire Employee After Failing for 4 Years to Accommodate Her Disability

Service spent more than a year attempting to address compatibility issues between promised speech recognition and its intranet.

In 2011, Dawn Dunphy decided she wanted to boost her professional skill set to pursue a new career in the federal government.

“I wanted to serve my country,” says Dunphy, who graduated from the University of Maine with a masters in business administration in 2013.

It worked. Upon graduating, Dunphy was recruited to her “dream job,” a financial management specialist position at an office of the Navy’s Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) in Philadelphia.

In December, four years after starting at her position, Dunphy is scheduled to be fired for an “inability to perform” due to a disability.

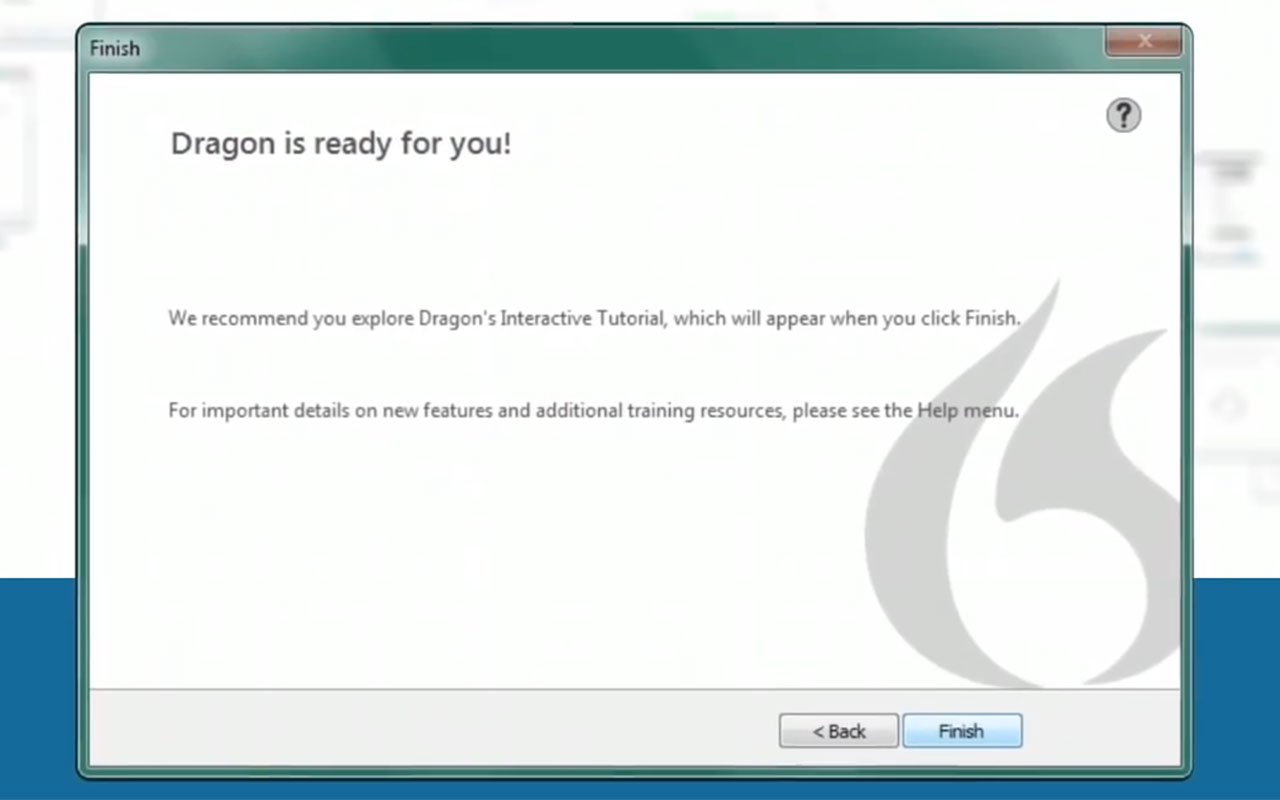

The Navy knew about Dunphy’s disability, which has drastically limited her use of her hands and prevents her from typing. She used a speech recognition program called Dragon NaturallySpeaking during the service’s recruitment event, the same program she used to complete her MBA coursework. The Navy promised “reasonable accommodations” to allow Dunphy to perform her job, internal documents and emails show, and the Dragon software was already pre-approved by the Defense Department’s Computer/Electronic Accommodations Program to function on the Navy Marine Corps Intranet platform upon which most of the agency’s computers operate.

When Dunphy reported to work, however, the program did not function. The software was not compatible with NMCI.

Dunphy was brought on under Schedule A excepted service hiring authority due to her disability. Three years earlier, in 2010, President Obama signed an executive order calling on federal agencies to collectively hire 100,000 disabled individuals over the next five years. He specifically directed them to use Schedule A authority to reach that goal.

Doomed From the Get Go

Dunphy said she spent the first two months of her job attending meetings and getting to know her new coworkers while waiting for the information technology team to install Dragon on her work computer and for other accommodations such as an automatic stapler and hole puncher. In January 2014, HP, the company that then operated the Navy’s NMCI contract, installed the software on her computer, but it did not work. The solution? Uninstall and reinstall the program, repeatedly. The contractor went through that cycle 75 times in three months, Dunphy said. Her entire first year progressed pretty much in that manner, she said, while she occasionally helped with non-computer based administrative tasks or sporadically had access to a non-NMCI computer.

“I shredded over 300 bags of outdated documents,” Dunphy said. “It wasn’t what I was hired to do, and it certainly is not what I expected to be doing...but it was one of the few ways that I was able to contribute to the team without access to the digital workplace that dominates every agency, and every workplace, in this day and age.”

After the administrative tasks dried up, Dunphy reverted to spending her days calling NMCI and internal IT. She explained her accessibility issues “over and over again,” she said. “It was endless.”

The trips from IT became so frequent her supervisor eventually told her she had to always remain at her cubicle to await their next visit—cutting her off from team meetings, internal events and even the office Christmas party. She heard an array of excuses—the microphone was broken, the constantly swapped-out computer was malfunctioning, Dunphy herself was not using the program properly—during that period.

“It was degrading, disheartening and demoralizing,” Dunphy said.

A Navy official asked about Dunphy’s case declined to comment on it directly, saying the department does not discuss personnel matters. The Navy maintains a variety of contracts with Nuance, Dragon NaturallySpeaking’s manufacturer, for services such as medical care and court reporting.

“The Dragon speech recognition software is approved for use on the NMCI network,” the Navy official said. “However, there are a variety of factors that may impact performance issues with a software application to include the interface and integration with other software systems and court reporting.”

Tom Vain, a Nuance engineer based in Maryland who went to Philadelphia for several on-site visits to find a solution for Dunphy’s issues, said the functionality problems stemmed from NMCI security settings. He would get the software working properly during those visits, only to have it malfunction upon rebooting the computer. Vain said he thought he and HP contractors had discovered a workaround and the last he heard Dragon was up and running properly.

He added Nuance had no formal agreement in place with the Navy and the company did not typically make on-site visits with clients. “We were trying to do them a favor, do them a solid,” he said.

None of those fixes ever provided a long-term solution and in August 2015 the Navy placed Dunphy on administrative leave. She received her normal pay while waiting at home, and returned to the office every three months to demonstrate to different levels of management that her promised “reasonable accommodation” still had not been delivered. For two years, Dunphy said, she has been waiting for the Navy “to either fire me or call me back.”

On Sept. 27, the Navy finally ended the waiting game. Dunphy received a notice of proposed removal, which stated, “This proposal is based on your inability to perform as a result of a medical condition.” The Navy said in the notice a Dragon official at Nuance informed it that even a maintenance and support contract “would not help solve the incompatibility issues.”

“We have dedicated significant time and resources in attempts to accommodate you without success,” Raymond Bauer, the head of Dunphy’s branch, wrote in her proposed firing notice. “There is no foreseeable resolution of the compatibility issues between the [Dragon] software and NMCI.”

Bauer continued: “This action is being taken because of your medical inability to perform the essential functions of your position. I believe that removal is the only remedy available to promote the efficiency of the service.”

The Navy originally scheduled Dunphy’s firing for October, before pushing it back to December. October is National Disability Employment Awareness Month at the Defense Department. On Oct. 24 at the NAVSEA Warfare Center in Philadelphia where Dunphy once reported and just four days before she was initially scheduled to be fired, a program analyst at the Defense Computer/Electronics Accommodation Program delivered an address on the theme of “inclusion drives innovation.”

Blame Game

Top leaders at the Navy and Defense Department have been aware of the problem for years. Randy Cooper, the Pentagon’s director of disability programs, said in a 2015 email that Dunphy’s case “appears to be a Section 508 issue.” He was referring to a 1998 amendment to the 1973 Rehabilitation Act that requires federal agencies to make all information technology accessible to people with disabilities.

In 2016, Dunphy filed a formal complaint to Defense for the Navy’s “ongoing and continuous noncompliance with Section 508.” She had previously filed a complaint with the Navy, but claimed that only resulted in retaliation from management. She has, over the years, brought the issue before her direct supervisor; her supervisor’s supervisors and so on, up the chain; her equal employment opportunity office; the human resources office; the IT office; and various other offices within NAVSEA and the Navy.

The process has led to finger-pointing and buck-passing with no resolution.

Maj. Timothy Lundberg, a spokesman for the Computer/Electronics Accommodation Program (CAP)’s parent office, the Defense Personnel and Family Support Center, acknowledged Dragon speech recognition software was and remains pre-approved for use on the NMCI network. Asked why that is the case since CAP and the Navy have known for years about the program’s lack of functionality, he said it was not part of the CAP’s responsibility.

“Assistive technology should be installed by the owning organization’s IT support staff,” Lundberg said. “Every organization has their own process for certifying products and determining what is a reasonable assistive technology accommodation.”

He added CAP has no authority to ensure the software it purchases on behalf of disabled employees actually brings Defense components in compliance with the Rehabilitation Act. CAP provides “general education” to agencies to inform them of their responsibilities, Lundberg said, but “the provision of reasonable accommodations is the responsibility of the employing agency.”

Between 2013, the year Dunphy was hired, and today, CAP has purchased 311 licenses for Dragon speech recognition software on the Navy’s behalf. It is unclear how many of those licenses went to employees working on NMCI machines, but Dunphy said one Navy IT employee told her more than 200 disabled workers were facing the same problem. Lundberg said CAP has no plans to stop purchasing Dragon licenses for the Navy.

A technical representative who served as an NMCI contracting manager in Dunphy’s office, who asked to remain anonymous due to possible retaliation, confirmed HP (which later broke off the portion of its business involved with NMCI into HP Enterprise, which itself subsequently sold off that portion of its business to DXC Technology) has for years sent employees to Philadelphia to get Dragon functioning. Each visit involved the contractors, internal IT staff, a contract manager and union representative, as well as Dunphy. They involved day-long and sometimes multi-day sessions. The Navy maintains an ongoing contract with its NMCI vendor to send employees whenever it requires troubleshooting assistance. The contractors put in a good-faith effort to find a fix, the manager said, but ultimately no single party was willing to commit the time and resources necessary to maintain permanent operability.

"What we have now is it’s not working," the contract manager said. "We’re out of compliance."

DXC Technology, which now fulfills the Navy's NMCI contract, referred all questions regarding disability assistance technology to the Navy.

Fighting On

The Navy took various steps to help Dunphy. After ongoing failures with the speech recognition software, the department in December 2016 provided Dunphy with a typist to sit with her and perform all her typing tasks. The effort was not a “reasonable accommodation,” Dunphy said, as her work as a contracting analyst requires technical editing and formatting. She went from dictating 110 words per minute with Dragon to 0.14 words per minute with the typist. She also had to constantly point at the screen to instruct the typist where to make edits, which her condition made exceptionally difficult and put her in “agony.”

The department also conducted two job searches to relocate Dunphy to a position that could better accommodate her, but came up empty.

Dunphy is planning to fight her firing. She was just assigned an administrative law judge at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in September. Discovery for the case will take place this month, with an initial conference call hearing scheduled for December. If the Navy follows through with her firing on the proposed date, Dunphy will be left to fight the case with no income and while searching for a new job.

“I am absolutely terrified about my financial situation, and had been crying every day,” Dunphy said. What especially concerns her, she added, is “the thought of being homeless in the middle of winter.”

She has felt pressured to settle with Navy, but vows to see the case through. Motivating her, she said, are the other disabled employees at the department who require typing assistance software or other accommodations. She said she has personally spoken to a handful of Navy employees facing the same functionality issues with Dragon.

The Navy would not confirm the total number of employees struggling to receive reasonable accommodations through speech assistance software, but said in Dunphy’s termination letter her removal “is consistent with those imposed on other employees who were medically unable to perform the duties of their position.”

A Navy official maintained the department is “committed to ensuring equal employment opportunities for all applicants and employees.”

“The department follows a detailed reasonable accommodations process to ensure that all employees receive fair and equal treatment,” the official said. “Each reasonable accommodation request is treated on a case-by-case basis as each employee has different disabilities and requires varying types of accommodations to help them perform the essential functions of their positions.”

Dunphy said she will continue fighting her case to ensure the Navy lives up to that ideal. The empty promises to disabled employees and subsequent push out the door has become a “known pattern,” she said. She thinks her chances of success are small, but she went back to get her graduate degree “expressly to become a civil servant” and now sees her battle as the best “opportunity to serve my country.”

“I can’t let the Department of the Navy keep doing this to their disabled employees,” she said.

NEXT STORY: What Evidence-Based Policymaking Doesn’t Do