State Department

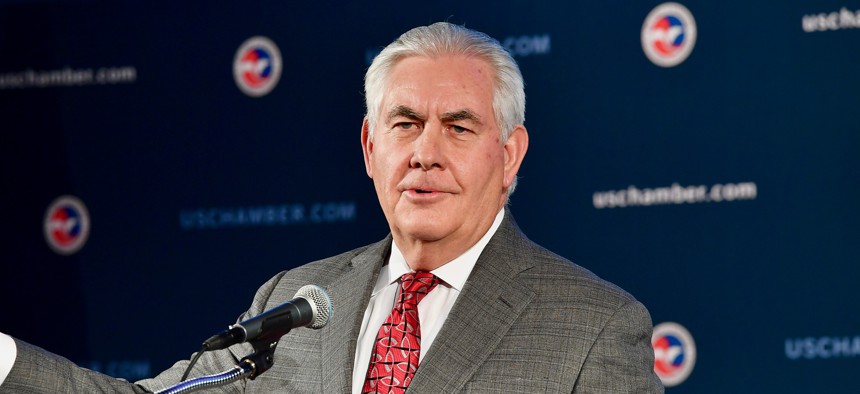

Why CEOs Like Rex Tillerson Fail in Washington

Although the former secretary of state’s contentious relationship with the president didn’t help matters, Tillerson’s management style left a department in disarray.

Rex Tillerson is hardly the first person to be targeted in a tweet from Donald Trump, but on Tuesday morning, he became the first Cabinet official to be fired by one. It was an ignominious end to Tillerson’s 13-month stint as secretary of state, a tenure that would have been undistinguished if it weren’t so entirely destructive.

Compared with expectations for other members of Trump’s Cabinet, the disastrous results of Tillerson’s time in office are somewhat surprising. Unlike the EPA’s Scott Pruitt, Tillerson did not have obvious antipathy for the department he headed; unlike HUD’s Ben Carson, he had professional experience that was relevant to the job; and unlike Education’s Betsy DeVos, his confirmation hearing wasn't a disaster.

The fact that Tillerson publicly clashed with Trump over everything from North Korea policy to relative IQ did nothing to make his job any easier, but his sorry legacy as secretary of state was sealed by a complete misunderstanding of the job before him. Rather than the nation’s top diplomat and an embodiment abroad of American values, Tillerson appeared to regard his mandate as little more than an exercise in cost-cutting and corporate reorganization. His time at the State Department seemed to test beliefs that are popular among many private sector professionals: skills that business executives bring to Washington can outweigh government experience, and almost every problem can be reduced to a matter of efficiency. That Tillerson should succumb to these beliefs is not altogether surprising given the benefits and blind spots of his experience in business.

Just a few weeks before he became the nation’s highest diplomat, Tillerson was CEO of ExxonMobil, one of the largest companies on Earth. It was a position he had held for more than a decade, one that required him to supervise a highly complex organization with nearly 70,000 employees and an annual budget that routinely topped $40 billion, all while successfully conducting business the world over. In other words, by the time he accepted the offer to join the Trump Administration, the Fortune 10 CEO had already enjoyed a long and distinguished career in the private sector, a track record that had endowed him with the experience, expertise, and administrative excellence that one could assume would make him a highly capable, even accomplished, secretary of state.

Tillerson certainly seemed to think so, notwithstanding the fact that he hadn’t spent any time in diplomacy or, for that matter, government affairs. He had barely introduced himself to the career civil servants at Foggy Bottom before he concluded that the agency they staffed was a portrait of bureaucratic mismanagement. “We had very long-standing disciplined processes and decision-making, I mean highly structured, that allows you to accomplish a lot,” he told reporters in July of his time at ExxonMobil. “Those are not the characteristics of the United States government.”

Initially, career diplomats were not unreceptive to the idea that a successful CEO might draw on his experience in the private sector to help renovate the bureaucracy at State. “To a person, we felt the department was in need of reform,” Linda Thomas-Greenfield, a 35-year veteran diplomat and former assistant secretary of state for African affairs, told Bloomberg in the fall. They withdrew their welcome, however, when, in Thomas-Greenfield’s words, they came to “understand” that the goal of the new secretary of state “was not to improve the organization but to deconstruct it.”

Or “redesign” it, the term Tillerson favored and one he used interchangeably as a noun and verb. “We’re going to redesign,” he told State Department staff during a town-hall meeting in December. “We’re not going to reorg. Reorg is taking boxes and pushing some of them together this way and pushing some of them together that way and then say we’re done. But what I’ve learned over 41 and a half years is when you do that, if you look behind the box, nothing’s changed about the way the work gets done. People are still dealing with the same inefficiencies; they’re still dealing with the same frustrations, complexities. You didn’t address the work. You just addressed the boxes.”

Tillerson’s delight for the eye-glazing jargon of management consulting was a hallmark of his “redesign.” In a report submitted to Congress in August, he rhapsodically outlined “an evidence-based and data-driven process to enhance policy formulation and execution, as well as optimize and realign our global footprint.” Less attention was lavished on the fact that, in his relish for optimization and realignment, Tillerson was also making a virtue of budgetary necessity. Indeed, even before he had had a chance to evaluate the institution with which he was now entrusted, Tillerson had largely acceded to the White House’s stated goal of slashing the State Department’s budget by nearly a third, this notwithstanding the objections of Republican Senators Lindsey Graham, John McCain, and Bob Corker, as well as the more than 120 retired admirals and generals who wrote a letter to Congress last February objecting to the cuts.

Tillerson’s acquiescence to the administration’s demands hardly endeared him to the career foreign-service staff, many of whom understood what Tillerson’s ambition for the State Department effectively amounted to: “No one is ever going to be as excited about the redesign as the secretary himself,” a State Department official told Vanity Fair after the town-hall meeting. “Everyone understands what that really means—it means people losing their jobs.”

A lot of people, in fact. Roughly 2,300, or 8 percent of the State Department’s total staff, is the target number for personnel cuts by the end of 2018. Tillerson got some help from the more than 300 civil servants who have already departed since the beginning of the Trump administration, many of them senior-level diplomats. One, Elizabeth Shackelford, blasted the secretary in her resignation letter when she exited in November. “I have deep respect for the career Foreign and Civil Service staff who, despite the stinging disrespect this administration has shown our profession, continue the struggle to keep our foreign policy on the positive trajectory necessary to avert global disaster in increasingly dangerous times,” she wrote. “With each passing day, however, this task grows more futile, driving the Department’s experienced and talented staff away in ever greater numbers.”

The brain drain, together with a startling delinquency in filling top spots—dozens of ambassadorships remain vacant, including those for Germany, Egypt, and South Korea, and, with Tillerson’s ouster, six of the nine top jobs at State are now empty—have been devastating for the department’s esprit de corps. “The place empties out at 4 p.m.,” a former assistant secretary of state told The New Yorker’sDexter Filkins in the fall. “The morale is completely broken.”

In many respects, Tillerson’s efforts may be regarded as a textbook example of a familiar phenomenon of new administrations—testing, in real time, theories of how government ought to work. Sometimes chief executives are explicit in this aim—say, Barack Obama’s attempt to transcend partisan politics or Sam Brownback’s endeavor to turn Kansas into a small-government utopia—but more often than not, the success or failure in discharging the responsibilities before them provides a referendum on implicit assumptions about government.

Having interviewed Tillerson and written a profile of the man during his tenure as secretary of state, Filkins concluded: “As far as I could gather, Tillerson doesn’t have much of an ideology, apart from efficiency.” Fair enough, but efficiency is always a matter of the means to a certain end; it is never an end in itself. Unfortunately, the latter view is common among many business professionals, for whom greater efficiency is synonymous with greater profit, the ultimate end of their labors. The same logic doesn’t apply to government agencies, however. They can always benefit from greater efficiency, but their ultimate success is never measured by profit margins. This may seem like a simple fact, but for corporate executives, like Tillerson, who have adhered to the mantra of efficiency for decades, it can lead to a confusion of ends and means when they enter government service. Such confusion threatens their ability to discharge their duties responsibly, but it can be lethal if it is supported by two assumptions that are fairly common among conservatives: The American government is hopelessly inefficient, and resolving this problem is the key to government working for a change.

These assumptions can hamstring executives entering government by convincing them that they have nothing essential to learn from their new peers who, in turn, have everything to gain from their experience. “I have sympathy with everyone with experience in the private sector who comes into a government agency and thinks ‘this is not how things worked at my old office,’” Daniel Baer, the former United States ambassador for the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe in the Obama administration, noted in an email. “I have less sympathy for folks who think, after a month or two, that they can simply import their prior world and impose it on their new one.”

Of course, for one who is certain that a system is fundamentally flawed, blithe dismissal is not only tempting, it seems downright efficient. If government is little more than an unwieldy machine that smokes and sputters, why waste time on the engineers who tend it?

But even beyond the risk of degrading the State Department’s mission in a misguided attempt to improve its operations, Tillerson made the greatest mistake for any CEO: he misallocated his time. According to Bloomberg, in the first eight months of his tenure, Tillerson traveled less than half as much as either of his predecessors in the Obama administration, preferring to hole himself up with a small coterie of subordinates in the executive suite of the Harry S. Truman Building and tinker with the elements of his “redesign.” For many observers, the choice communicated that Tillerson failed to appreciate or perhaps even fully understand the human elements of diplomacy, either as a global ambassador for American values or the leader of an essential organ of government. “When it comes to building a State Department for the next generation, I am hard pressed to name a single thing Tillerson has said or done to attract the best talent,” Derek Chollet, a former assistant secretary of defense for international-security affairs in the Obama administration, wrote in a column for Foreign Policy. “If anything, he’s driving people away.”

Given his successful tenure at ExxonMobil, this failure makes for perhaps the most surprising oversight of Tillerson’s tenure, that he seemed to forget the fact that, while the requirements of leadership and management can be usefully sorted, they remain symbiotic. Just as gross mismanagement can try the commitment of even the most dedicated team member, no amount of efficiency gains in an organization can compensate for sending a message that an employee’s work is meaningless. “People need to be brought into a vision of what is possible,” Baer wrote of Tillerson’s stewardship of the State Department in another piece for Foreign Policy. “Their good work deserves to be acknowledged, and they need to feel that the secretary of state has their backs.”

At the December town hall, sensing that his job was in peril, Tillerson tried to win some allies and make amends. “When I came to the State Department, I didn’t know any of you,” he said. “I didn’t know anything about your culture, I didn’t know anything about what motivates you, I didn’t know anything about your work, I didn’t know anything about how you get your work done.” It was a bracing admission, courageous even, but insofar as Tillerson would go on to highlight the crucial importance of having integrated the USAID and State Department global address lists—“if you’re spending 30 seconds to a minute every time you try to engage with that system, sitting there watching it, and I multiply that times 25,000 people times how many encounters a year”—in more ways than one, it seems clear he never learned his lessons.