Analysis: Trump’s Deregulatory Record Doesn’t Include Much Actual Deregulation

A review of Trump's stated war on regulations doesn't find many successful repeals. But it is hurting regulatory enforcement in quieter ways.

One year ago, the Trump administration’s deregulatory push was in full swing. The administration was preparing a proposed rule to repeal the Waters of the United States (WOTUS) regulation, and to delay and repeal the restriction of methane emissions from oil and gas extraction on public lands.

Surely these well-publicized deregulatory initiatives which the Trump administration has made a big show of taking credit for have taken effect by now.

Well, not exactly. The WOTUS proposal has not been finalized, and the methane extraction rule is tied up in a thicket of court cases.

President Trump’s record on deregulation has gotten a great deal of attention. He brags about it regularly. It is often placed alongside the tax cuts passed by Congress when his chief accomplishments are recounted. To listen to the president (or the media), one would think that thousands of regulations were repealed.

But as the WOTUS and Bureau of Land Management extraction rules indicate, the actual extent of deregulation is much more limited. At the same time, other moves to dismantle the “administrative state” have quietly been more effective.

No more easy routes

Early in the Trump administration, Congress used the Congressional Review Act, a statute that allows the Senate to bypass the filibuster to repeal recently issued regulations. By May 17, 2017, Congress had repealed 14 Obama regulations using the CRA in a wide array of policy areas. They would add one more regulation from the Consumer Protection Financial Bureau by the end of 2017.

But these repeals are largely the work of Congress and frequent punching bag for President Trump, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. And now, most Obama-era regulations are off limits for the CRA (although Congress has explored expanding its use). That leaves President Trump and his administration to rely on the typical route for writing and revising regulations – the executive branch – if they want to repeal any more of the thousands of regulations issued during the Obama administration.

Making announcements about a desire to repeal regulations is easy. President Trump did so in December (although his claim that 22 regulations had been repealed for every new regulation was vastly exaggerated). Actually repealing significant regulations is much harder, as the administration is finding out.

An agency must start by developing a proposal to repeal a regulation. This must often be accompanied by a detailed economic analysis of the repeal. The proposal and the analysis are then sent to the Office of Management and Budget for a review. When that review is complete, the proposal is published in the Federal Register for public comment. Agencies must review the public comments, respond to them, make any changes they feel necessary to their proposal and analysis, and then resubmit it to OMB before publishing a final rule. Finally, the rule is subject to litigation.

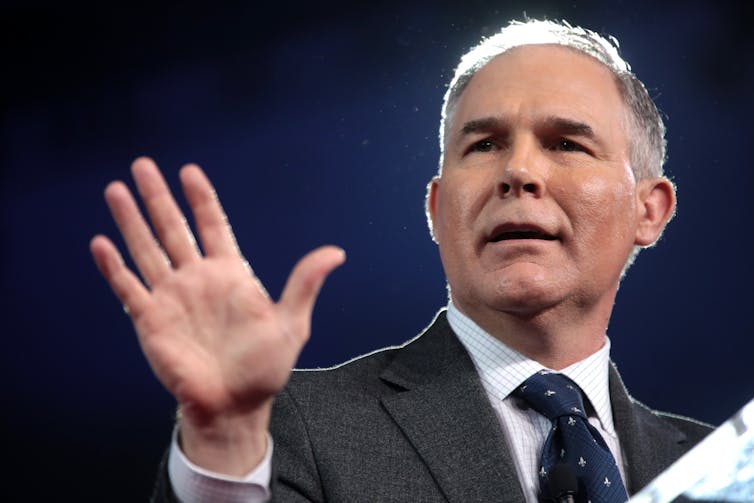

To navigate this process takes time and expertise. President Trump and his Cabinet members, particularly Scott Pruitt at the EPA, have instead tried to rush through the many steps of this process. This has meant that the last step, the litigation over regulatory repeals, has proven particularly problematic for the administration. At the EPA, courts have struck down delays or repeals of regulations six times already. This pattern holds across the government.

Another kind of damage

Part of the problem for the Trump administration is that while they have been hasty in trying to repeal regulations, the Obama administration was thorough in promulgating them. Over the course of eight years, Obama appointees solicited comments on their proposals, did detailed economic analyses, and built strong cases for many of their regulations. For example, the former EPA administration compiled a 1,217-page analysis done over years to buttress its fuel economy rules, while the current administration generated a 38-page document dominated by auto industry comments to justify reviewing and rescinding them.

In order to repeal these regulations, the Trump administration will have to convince courts that there are sound legal reasons to ignore all of this work. The statute that governs the creation of regulations, the Administrative Procedure Act, requires agencies to demonstrate that they are not arbitrary and capricious.

To do so, the Trump administration will have to rely on the expertise that lies within the federal bureaucracy. But President Trump and his appointees have regularly denigrated those whose help they now require. As a result, many of the most talented people at the agencies have left public service. At the EPA alone, more than 700 employees have left during this administration.

This means not only has the administration failed thus far to repeal many regulations beyond those overturned by Congress using the CRA, but their prospects for doing so in other cases are not strong. These cases include the WOTUS regulation, the Clean Power Plan to limit carbon emissions from power plants, and the recently announced plans to roll back emission standards for automobiles and take on California over their auto emission requirements.

Stephen Bannon listed the deconstruction of the administrative state as a goal of the Trump administration. The repeal of regulations is often trumpeted as the most important sign that Trump is succeeding. But while the administration is failing at the piece of deconstruction they are talking about most loudly, there are signs that they are succeeding in other ways.

The first is the enforcement of existing regulations. While the Trump administration has ramped up enforcement of immigration regulations, it has ratcheted down enforcement of environment and worker safety requirements. This selective pattern of enforcing regulations sends signals to firms that they don’t need to worry about complying with the law when it comes to the environment or public health.

Meanwhile, there has been an exodus of employees from the federal government which will likely have a corrosive long-term effect. Replacing talented public servants is not something that can be done overnight, even by a new administration dedicated to doing so. Training these new government employees will take even longer. As government becomes less effective because of the talent drain, faith in government diminishes further and a cycle of cynicism about public service is made worse.

![]()

The Trump administration has declared war on the regulatory state. But the things the administration is reluctant to take credit for, notably not enforcing the law and driving out talented public servants, are likely to have a much larger impact than its largely nonexistent regulatory repeals.

![]()

This post originally appeared at The Conversation. Follow @ConversationUS on Twitter.