How to Keep Your High Performers Happy

Plus, ways to prevent toxic workers from corrupting your team.

Based on the research and insights of Jeff Hyman , Carter Cast, Dylan Minor and Brenda Ellington Booth.

Everyone wants to fill their organization with top performers. But superstars are in high demand, so you need a clear strategy to recruit and retain them.

At the same time, don’t ignore the drag that problem employees can have on the organization. By some measures, the liability that comes with bad employees is more pronounced than the boost you get from superstars.

Here, Kellogg faculty offer advice on how to nurture superstars and rid your organization of “toxic” workers.

1. Challenge is key in keeping valuable employees.

Above all else, top performers care about challenge, according to Jeff Hyman, an adjunct lecturer of management and organizations and chief talent officer at Strong Suit Executive Search. He is also the author of Recruit Rockstars.

Stretch assignments are central to keeping rockstars engaged. Organizations should assign rockstars a senior executive as a mentor. In addition to seeking out new opportunities for them, mentors should provide career coaching and act as a sounding board for difficult situations. “And,” adds Hyman, “they are the ones who should be held accountable if that rockstar leaves.”

While providing challenge is crucial, do not ignore compensation.

Hyman advises tossing out the usual pattern of single-digit raises for all, with perhaps 1 percent for low performers and 5 percent for rockstars. Instead, give top performers as much as a 20 percent raise, while giving low performers none.

Even if you do everything right, some rockstars inevitably leave, Hyman cautions. When that happens, make sure you conduct a thorough exit interview to find out if there are organizational problems that will prevent other high performers from thriving.

“If it was something you missed, if the person felt underappreciated or wasn’t mentored closely enough, then you need to figure out what led to that oversight and solve that problem before trying to attract other rockstars,” he says.

2. Tailor a career path for superstars.

Carter Cast, a clinical professor of innovation and entrepreneurship, suggests tailoring a professional development plan for your superstars.

“It’s important to put your arm around them and say, ‘I think you have a lot of potential, and one of my key jobs is helping you reach your potential. I will get satisfaction out of helping you do that,’” Cast says.

One important but often overlooked skill to nurture is associative thinking—making connections between seemingly disparate ideas. Developing this skill can spur high-potential employees to become more creative and innovation-minded.

When Cast was the CEO of Walmart.com, he had an interesting exercise to get his high-potential employees thinking creatively.

The first 20 minutes at Monday senior leadership meetings were devoted to a simple question: What did you see over the weekend that struck you? People then had to explain how the company might act on these new trends or observations.

“We had people bring up clothes, devices, articles, advertisements, circulars, you name it,” Cast says.

It is also crucial to make high potentials feel like they are improving their skills and working on projects with value.

But make sure you do this with input from the employee. Cast was once grooming a top employee to become a general manager. But the employee was not looking to become a CEO. He wanted to become a CMO.

“I had the wrong assumption,” Cast says. “He wanted to be a functional expert. So we stopped and I said, ‘Let’s look at your skill set in marketing and where you think you have gaps, and let’s start talking about how we can fill those gaps.’”

3. Should you hire a superstar or fire a toxic worker?

While most people know superstars can improve an organization through their strategic thinking and tenacity, research shows they have another superpower: they can improve the work of the people they sit near.

Dylan Minor, an assistant professor of managerial economics and decision sciences, and a colleague used information on the performance of more than 2,000 workers at a large technology firm. They gave workers a ranking of either high or low for both speed and quality. Then they literally mapped out where each employee sat and analyzed how each person’s work shifted over time as their neighbors changed.

They found that top performers boosted performance in coworkers within a 25-foot radius by 15 percent. That translated into an estimated $1 million in additional annual profits.

But what about workers at the other end of the spectrum?

“Once a toxic person shows up next to you, your risk of becoming toxic yourself has gone up,” Minor says. And while positive spillover was limited to about a 25-foot radius, with toxic workers, “you can see their imprint and negative effect across an entire floor.”

What’s more, these toxic workers are extremely costly. In another paper, the researchers found that the cost associated with employing a toxic employee is greater than the benefit of employing a top performer.

A top 1 percent superstar—a very rare high performer—brings an extra $5,300 in value by doing more work than an average employee does. But replacing a toxic worker with an average one creates an estimated $12,800 in cost savings over the same period by reducing the cost of turnover around that toxic worker.

4. What to do with a toxic worker.

Given this, what can organizations do to avoid bringing toxic workers into their ranks?

“My big philosophy is hire slow, fire fast,” says Brenda Ellington Booth, a clinical professor of management and organizations. She is also an executive coach who often helps companies deal with toxic employees.

“The most serious toxic worker is one that has any kind of power or authority, so a manager,” she says. “My favorite phrase is, they tend to kiss up and crap down.”

Booth advises companies to be sure to check the references of potential new hires and to look beyond the two or three names they supply.

“Ask for references that they don’t give you,” she says. “Who was your previous employer? Do you mind if I called your old boss?”

Additionally, see if there is a way to test someone out first.

“If [you] have the luxury, hire them on as a consultant initially, and see how they get along,” she suggests. “Yes, they’ll be on their best behavior, but usually you’ll see some telltale signs.”

What is Booth’s advice if, despite your best efforts, a toxic worker lands on your team?

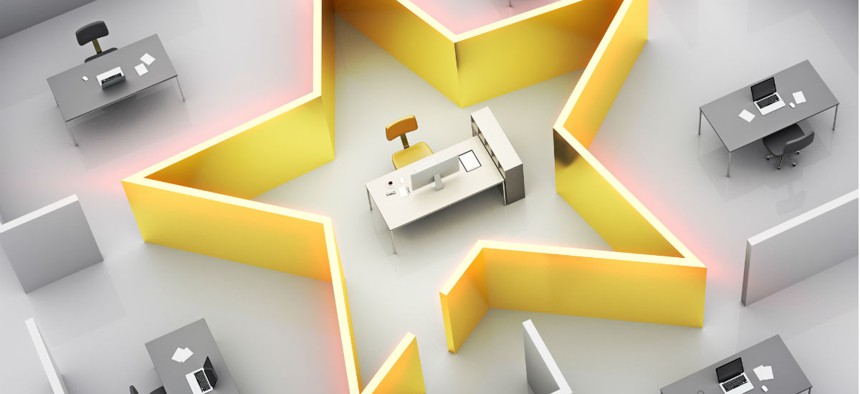

If they can’t be reformed, and firing them is not practical—because there are many organizations where that is no easy task—Booth says to isolate them as much as possible.

“At least put them in a place where they can do a minimum amount of harm,” she says. “Put them on special projects. Hopefully, they’ll get the message. Sometimes people never do. But at least don’t have them as a central hub of the organization where there’s a lot of direct reports, or they have to interact with a lot of people in the organization.”

5. Identify your own liabilities.

What happens when the problem behavior isn’t the obnoxious guy down the hall? Instead, the problem is you.

Here, Cast weighs in again, having studied common career “derailers” for his book The Right—and Wrong—Stuff: How Brilliant Careers Are Made and Unmade.

“We're not talking about people that lack talent,” he says. “We're talking about people who don't reach the expected level of performance.”

Of course, there are lots of reasons why careers derail. No one can ignore the powerful role that racism, sexism, and ageism play in many workplaces.

But, Cast says, it pays to understand how you may be holding yourself back.

“We all have derailment characteristics,” he says. “So it's not a question of whether you have one. It's a question of how you manage around it so it doesn't bite you.”

The biggest reason people derail, Cast found, is relational issues with other people.

“You're defensive. You're overly ambitious, and you sort of bruise people on your way to the corner office,” he says.

To tackle this, Cast suggests a healthy dose of self-reflection.

He also found that when the thrill goes out of the job—when you lose that fire in your belly—it can signal that you may be about to stumble.

“You are doing this job and you shouldn't be doing it because it doesn't fit your needs. It doesn't fit your motives,” he says. “But if we can uncover what our motives are, we can put ourselves in the right context at work so we're happier.”

And there is no need to do all the soul searching alone.

“Seek counsel from friends and seek counsel from coaches,” he says. “I never was a big fan of using executive coaches or management coaches. That was just my own ignorance. They can really help you put together a game plan on how you can attack some of the areas.”

This piece was previously published in Kellogg Insight. It is republished here with permission of the Kellogg School of Management.