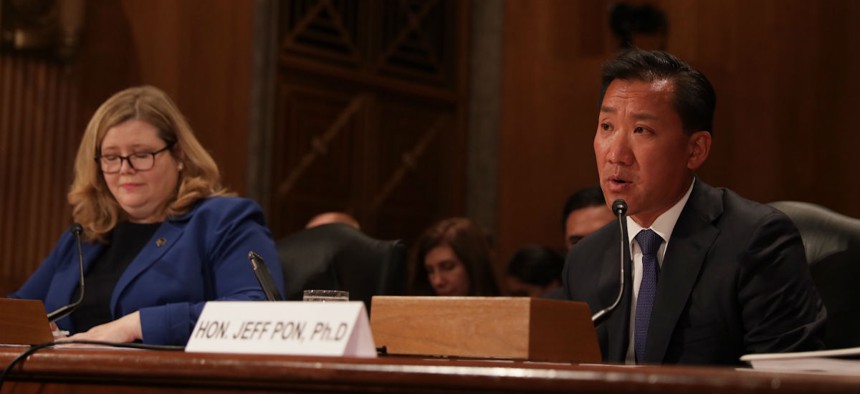

GSA leader Emily Murphy and OPM chief Jeff Pon testify before a Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs subcommittee Thursday. Tim Grant/OPM

OPM May Scrap the Most Significant Change in Its Reorg Plan

Agency may not move itself into the executive office of the president after all, OPM director says, but plans unilateral action on other parts of the reorganization this year.

The Trump administration is moving forward with initial steps in reshuffling its responsibilities for personnel management, as it called for in its recently unveiled government reorganization plan, but is now suggesting it may not implement some of the most significant proposals at all.

As part of the first phase of the reforms, the Office of Personnel Management plans to shift its Human Resources Solutions division to the General Services Administration. Functions that would be relocated include OPM’s fee-for-service offerings such as HR consulting, training, occupational assessment tests and the job vacancy listing site USAJobs. The details of the changes are being sorted out by task forces within OPM and GSA, Jeff Pon and Emily Murphy, the respective leaders of the two agencies, testified before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Reform Regulatory Affairs and Federal Management subcommittee on Thursday.

Those groups are reviewing what actions they can take unilaterally, but Pon and Murphy were confident most of that shift can occur without legislation. Some areas, such as USAJobs, the online repository of federal vacancies across government, may be statutorily tied to OPM, they said.

The agencies plan to start implementing the changes they have the authority to make in the next three to four months, Murphy said. Pon said he does not expect some of the more significant proposed changes to begin until 2021. That would include relocating the administration of retirement processing and federal employee benefits, including the health care marketplace that serves more than 8 million workers, retirees and their families. Subcommittee Chairman Sen. James Lankford, R-Okla., said the lack of concrete plans surrounding that part of the proposal came as a “news flash” to the lawmakers.

Perhaps the most controversial of the proposals is to move what remains of OPM to the White House, under the Executive Office of the President. Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., said she was concerned that turning OPM into a policy shop at EOP would lead to “HR policy for career staff [being] based on politics and not on merit.” Pon said his role as OPM director would remain and the oath he swore to “be a defender of merit systems” without political influence would continue to guide him.

“I’m still a direct report to the president, whether I’m across the street or not,” Pon said. He added there is “enough separation between politics” and core OPM functions “that it will continue to do what it’s supposed to do.”

After the hearing, the director, who was sworn into the position in March, said the change may not happen at all.

“We’re seeing whether or not we need legislation for that to happen because of the independence that OPM has as the civil service leader and also the civil service and merit system principles enforcement wing of the government,” Pon said. “If we can move that to the executive office of the president, we will, but I believe there needs to be more analysis as to whether or not that can happen without legislation, and if we do have legislation, does that makes sense. And we’ll decide on that after we’ve had conversations with key stakeholders, interagency coordination and so on.”

The OPM proposal has been met with widespread criticism, ranging from lawmakers to former Trump officials that helped launch the reorganization effort. Critics largely focused on the move to EOP, expressing fears it would undermine the nonpartisan civil service. Lankford said the other ideas could hold merit if they were proposed with the proper intentions.

“If these three OPM services can be transferred into GSA, it must be done to improve services to our federal workforce and to provide efficiencies from what many would equate as a merger,” Lankford said.

Sen. Heidi Heitkamp, D-N.D., the top Democrat on the subcommittee, also expressed an openness to the proposal.

“I am not afraid of big ideas and Congress cannot be reflexively dismissive simply because it changes the status quo,” Heitkamp said.

She voiced skepticism, however, that the OPM proposals would address the issues the agency faces.

“One of the critical questions in a reorg plan is what is the problem you’re seeking to solve, and how will this reorganization actually solve that problem,” Heitkamp said. “Somehow just rearranging the chairs, or who sits where, in my opinion, doesn’t solve some of the problems that I see that need to be solved within OPM.”

Pon defended the plan as one that would give the OPM director a more prominent seat at the table.

“I want to be clear on one point,” he said. “This proposal is not a secret plan to fire civil servants. Rather, it is an opportunity to elevate the federal workforce management function and maximize the operational efficiency of human capital services.”

Pressed on where the change proposals originated, Pon declined to say, noting only that it was an “iterative process” with the White House and OPM “trading information back and forth.”

Murphy said her agency was better suited to handle the transactional services such as benefits administration and retirement processing, as GSA is simply an “administrative office” and not a policy agency.

“Centralizing the transaction processing and IT for administrative functions in GSA, where it is our mission to provide excellent mission-support services, will allow for OPM to focus on their core strategic mission,” Murphy said.

OPM and GSA could run into trouble as they try to implement its plan unilaterally, as lawmakers are on the verge of passing a spending bill that would require congressional oversight for any reorganization actions taken at the agencies. Lawmakers repeatedly stressed at the hearing that the administration should engage them throughout the process, and Pon and Murphy vowed to regularly brief the committee on their plans.