NPS released a female wolf on Isle Royale, Oct. 2, 2018 Jim Peaco/NPS

Restocking Wolves On Isle Royale Raises Questions About Which Species Get Rescued

The National Park Service is moving wolves to Isle Royale in Lake Superior to replenish a small pack on the island. Wolves prey on moose, which are overgrazing the island. It does't hurt that they are charismatic.

Isle Royale is one of the most remote U.S. national parks. It stretches across one large island, its namesake, and more than 400 smaller ones in northwest Lake Superior. The park’s main draws are wilderness and wildlife, including beaver, otters, moose, martens and – for the moment – a very few wolves.

This fall the National Park Service has released four wolves captured from the mainland on Isle Royale. Once there were 50 wolves on the island, but inbreeding, climate change and disease all but wiped them out in the past decade. Meanwhile, moose – the wolves’ chief prey – are eating island greenery down to the nub, adversely affecting many other species.

Restocking wolves on Isle Royale is the first time that the National Park Service has intervened in a designated wilderness area to manipulate a predator-prey relationship. The agency plans to move 25 to 30 wolves to Isle Royale in the next three to five years and spend about US$2 million over 20 years to maintain the population.

Supporters call this plan a “genetic rescue,” but skeptics say nature should be allowed to take its course. We think this is unlikely to happen, because wolves have friends in high places in the scientific establishment and the federal government.

As environmental journalists and journalism educators in the Midwest, we take a special interest in how the Great Lakes’ ecological problems are defined and communicated. In our view, media attention and the cultural history of the wolf-moose relationship on Isle Royale have outweighed most scientific qualms about putting a finger on the ecological scale.

Two charismatic species

Wolves and moose are charismatic megafauna whose fate on Isle Royale has attracted widespread public interest and media attention. Both species have cultural meanings that extend beyond their predator-prey relationship.

Moose were first sighted on the island around the turn of the 20th century, and scientists have been examining them continuously since at least the late 1920s. Wolves arrived around 1949. For decades they could reach the island by crossing over ice from the mainland in winter. Now climate change is altering ice formation in Lake Superior, leaving wolves on the island isolated.

Isle Royale is located in the northwest corner of Lake Superior. NPS

Isle Royale measures just over 200 square miles and is well-suited for ecological research. Animals exist there in relatively small (and thus, countable) numbers. The island is easily accessible by boat, ski-plane and seaplane, weather permitting.

And it is isolated. More people visit Yellowstone National Park on a single summer day than trek to Isle Royale in an entire season, which runs from May into October. There are no roads and no motors allowed. The only people present in winter are park employees and scientists.

Grey wolves in the Great Lakes region have been moved on and off of the U.S. Endangered Species List several times in the past 20 years. But they are not as controversial here as they are in the western United States – perhaps because fewer farmers and ranchers are affected by their presence, or because even though their numbers dipped to a few hundred in the 1960s, they never really went away.

Altering natural processes

In 1934 Adolph Murie, one of the first biologists to conduct research at Isle Royale, suggested that introducing a native species to prey on moose, such as bears, cougars or wolves, would “add materially to the animal interests of the island.” By some accounts the first pair of wolves crossed an ice bridge to the island from Ontario in 1949. Three years later, writer and wolf advocate Lee Smits brought four more wolves from the Detroit Zoo to the island.

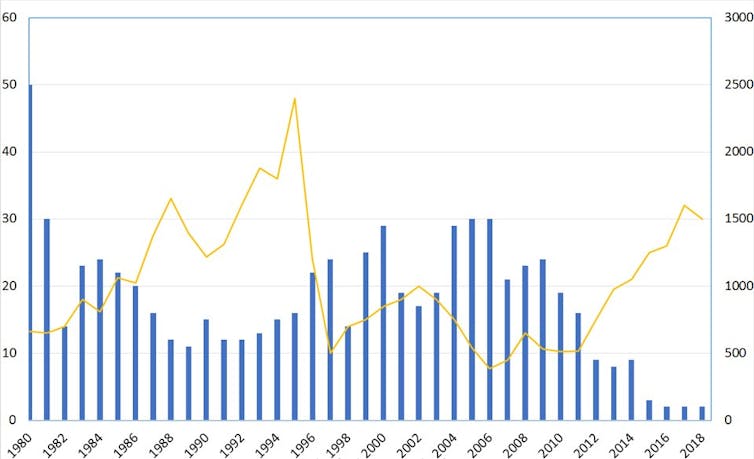

Over the next several decades the wolf population grew, peaking at 50 in 1980 and then declining due to inbreeding, fighting among wolves, disease and starvation. Even with wolf predation, the moose population swelled, shrank and swelled again, peaking in 1995 at about 2,450. Although Murie had hoped these two species would achieve ecological balance, wolf and moose numbers fluctuated between peaks and crashes.

Populations of wolves (blue) and moose (yellow) on Isle Royale have fluctuated between peaks and crashes in recent decades. NPS

Today, if there are indeed two “native” wolves left – only one has been spotted since January 2017 – they are a father-daughter pair, born to the same mother, whose mating efforts have failed. In its report advocating for the stocking program, the National Park Service concluded that “[a]t this time, due to the low number remaining, genetic inbreeding, and the remoteness of Isle Royale, natural recovery of the population is unlikely due to tenuous nature of ice bridge formation.”

Some observers would rather let natural processes play out. “For me, waiting for ice bridges to form makes the most scientific and ecological sense,” says Seth Moore, director of biology and environment for the Grand Portage Band of Chippewa in Minnesota. “We are also worried that wolves stocked on the island will escape, perhaps with different parasites, and come to Grand Portage,” where five packs of wolves now live.

A male and a female wolf, trapped on the Grand Portage reservation, were released at different locations on Sept. 25, 2018, and two more females were released in early October. Another female wolf trapped at Grand Portage died in custody on Sept. 27 before it could be moved to the island.

Who to save next?

Even if the plan works well, wolf sightings will remain rare because of the island’s terrain and topography. “You’ll find tracks in the mud and scat, and hear occasional howling,” says park superintendent Phyllis Green. “They run our trails mostly at night when we’re not on them and they’re not very visible to the public. If people want to see wolves, they need to go to Yellowstone.”

Genetic rescue is a relatively new idea in wildlife biology and has never been attempted in a national park ecosystem, although the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has transferred panthers from Texas to south Florida to save an isolated and inbred population there. The wolf project raises many questions. If it works, will the National Park Service undertake similar efforts elsewhere? Should it? How will it choose which species to save? Is inbreeding in a small population a more serious threat than the loss of an animal in an ecosystem, however contained? What about birds, fish, insects or plants? And we haven’t even mentioned species threatened by climate change.

As conservation advocates know well, some species have more public appeal than others. “Rescuing” a charismatic species can have great public relations value, especially if it generates dramatic images. If the National Park Service attempts more genetic rescues, we expect media-friendly species will be the likely targets.

![]()

Mark Neuzil, Professor of Communication and Journalism, University of St. Thomas and Eric Freedman, Professor of Journalism and Chair, Knight Center for Environmental Journalism, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NEXT STORY: Analysis: How to Fix the Confirmation Process