Does the Hatch Act Need a Makeover for the Trump Era?

White House resistance to the special counsel raises questions about enforcement.

The Office of Special Counsel wants “to put a big roll of masking tape over my mouth!,” said Counselor to the President Kellyanne Conway, speaking to Fox News in June two weeks after that independent office recommended her dismissal for repeated violations of the Hatch Act.

Her declaration followed repeated brushes with the 1939 law intended to keep federal employees at arm’s length from electoral politicking. It came after the White House social media director drew his own reprimand from the special counsel, and just as top advisers and family members of President Trump, namely his daughter Ivanka, have been accused by a nonprofit ethics group of violating the act by sending Tweets using the campaign slogan “Make America Great Again.”

The OSC itself, in modernizing Hatch Act guidance for the social media age, has issued detailed instructions to federal employees warning against such language as “resistance” or “impeachment” in the political context of the Trump era.

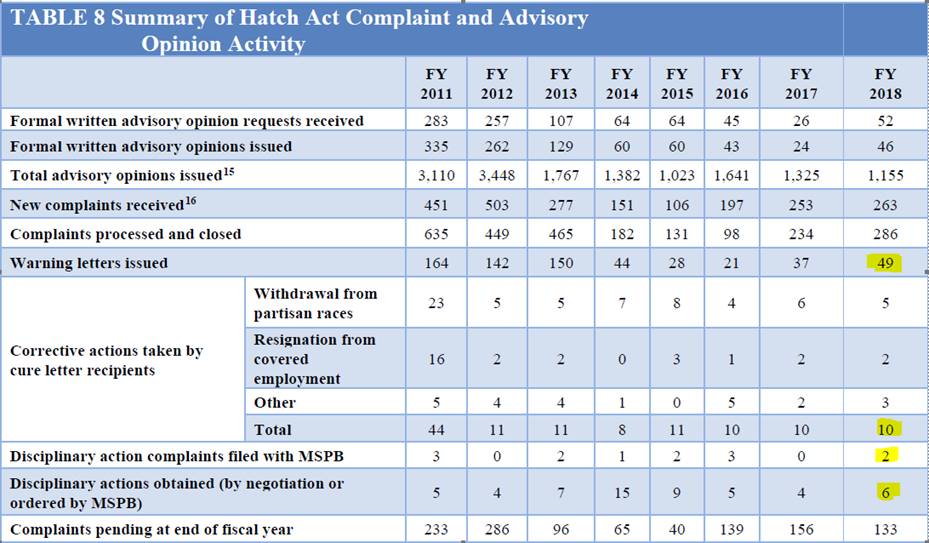

Hatch Act clashes in recent years have singed both Republican and Democratic administration appointees. Measured in numbers of violations reported, investigated and acted upon, the Trump administration has produced a small uptick. In fiscal 2018, 67 employees—including federal, state and local employees—violated the Hatch Act, up from 51 employees in 2017, OSC reported to Government Executive. Those tallies are similar to those during President Obama’s second term. For the first two quarters of fiscal 2019, OSC has submitted 23 warning letters and produced three corrective and two disciplinary actions.

But the defiance by the Trump team may be unprecedented. In his all-out defense of Conway sent to OSC on June 11, White House Counsel Pat Cipollone blasted OSC for its “overbroad and unsupported interpretation of the Hatch Act” and faulted the investigative agency created in 1978 for failing, despite its multiple meetings with Conway, to provide her with sufficient time and “an opportunity to respond.” Most telling, the top White House lawyer questioned whether the Hatch Act even “applies to the most senior advisers to the president in the White House.”

Trump was quick to declare he had no intention of firing Conway. He also forbade her from even testifying at a June 26 hearing of the House Oversight and Reform Committee, which resulted in her being subpoenaed.

There is a new risk, as warned against by Special Counsel Henry Kerner—himself a Trump appointee—that having an uncooperative White House protecting a highly visible appointee will, “if left unpunished, send a message to all federal employees that they need not abide by the Hatch Act’s restrictions.”

Perceptions of Enforcement Disparity

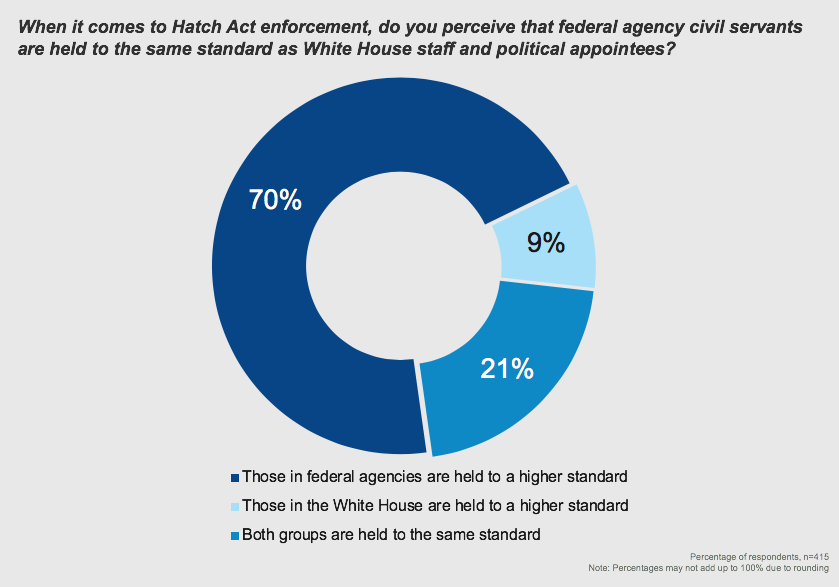

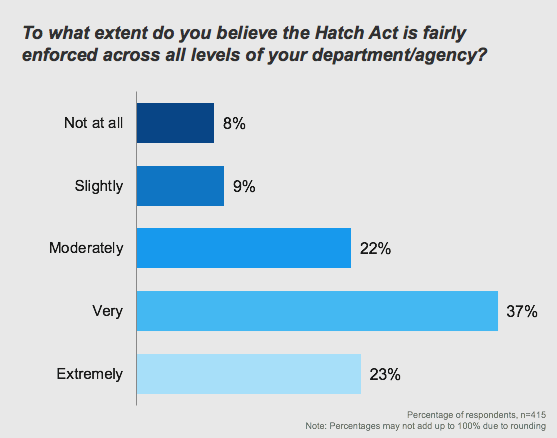

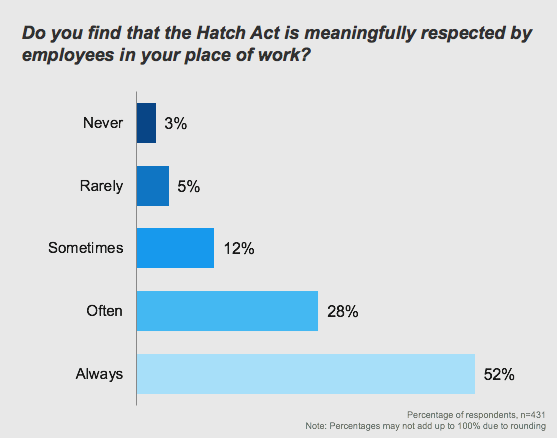

Those fears may be justified. Most federal employees think the Hatch Act is well enforced, but that White House staff get favorable treatment, according to an online survey by Government Executive and the Government Business Council taken over several days in early July. Nearly half of the respondents (47%) are supervisors.

A clear majority (70%) said federal employees are held to a higher standard than White House staff and appointees.

Nonetheless, most respondents (60%) believe the Hatch Act is fairly enforced at their agency, and a full 80% believe the Hatch Act is meaningfully respected by their colleagues.

The survey has a margin of error of 5% with a 95% confidence interval.

Confusing Guidance

Government Executive interviews with attorneys who have experience representing clients who ran afoul of the Hatch Act suggest that it may be time for Congress to clarify whether the act should be enforced among political appointees who won their jobs outside of Title 5 authority.

Under current law, the prohibitions against electioneering apply to any employee of an executive branch agency except the president, vice president, Government Accountability Office, those in certain positions at independent agencies, those in the uniformed services (who have their own restrictions) and those employed by the government of the District of Columbia. Kellyanne Conway is employed by the White House under Title 3.

“As a result of Conway’s situation, it does seem like the current administration is not very interested, outside of OSC, in enforcing the Hatch Act said,” said John Mahoney, a Washington, D.C.-based federal employment law attorney. “Things are becoming more politicized throughout the executive branch, so it’s important that the OSC aggressively prosecute Hatch Act violations—even though it has no jurisdiction over political appointees” other than to make recommendations.

Mahoney’s clients represent a cross-section of the ways in which people run afoul of the Hatch Act: one ran in a partisan election (that client had to resign); a federal manager added under his official email signature block the words “making American great again” (after an investigation he opted to retire); and a third was a supervisor who shared political articles within his work unit on LinkedIn (he got a three-day suspension).

Though the prospects for enforcement should not depend on which political party an employee is advocating, Mahoney said, in the current era, there is “a big danger that federal employees engaging in prohibited political activity in support of the administration may not be aggressively prosecuted by individual agencies.” Also slowing the enforcement process, he added, is the continuing backlog and lack of a quorum at the Merit Systems Protection Board, which adjudicates complaints referred by the OSC (though it cannot take cases as the original jurisdiction, only appeals).

“The tone is set by the administration,” said Joanna Friedman, a partner with the Federal Practice Group who focuses on federal employment and labor law. The rise in OSC’s Hatch Act activity “seems to tell you either there are more violations or that OSC is paying closer attention, perhaps because the violations are more blatant,” she said. OSC’s “unprecedented letter to the president about one of his senior counsels shows that OSC is taking Hatch Act violations very seriously.”

Friedman expressed surprise that the White House hasn’t argued more forcefully that the Hatch Act doesn’t apply to Title 3 presidential appointees, of which Kellyanne Conway is one, although, she said, “that should be no excuse for White House officials to engage in campaign activity while being paid by tax dollars.”

Overall, although OSC has published guidance on “do’s and don’ts,” there is still confusion over social media postings and what content can constitute a Hatch Act violation, Friedman added. “In this day and age, it has become more complicated to know what you can and cannot do, especially given that President Trump started his re-election campaign almost immediately after taking office. But that being said, it is crucial for those at the top to set the example for those watching. There should not be one set of rules for leadership and another for everyone else.” Perhaps what is needed is more training.

‘It’s Like Playing a Game of Clue’

The complexity of current-day enforcement also bothers Ward Morrow, the assistant general counsel at the American Federation of Government Employees. “If a Cabinet secretary and staff can’t keep it straight, how can a GS-5, who has been in government two or three months?” he asked. Agencies do provide training through their ethics offices, but “it’s like the service icon on a Microsoft agreement—no one has read down into the weeds on this,” said Morrow, who in 16 years has represented hundreds of accused violators.

“Everyone knows you cannot run for federal office if you’re a federal employee, and you can’t raise money,” he said. But, for example, “what happens when you get down to two employees who are best friends and believe they have the same political beliefs, and they email that ‘the candidates’ debate is tonight, you wanna watch?’ Is that partisan activity?”

If the times when an employee can use social media—when not in a government building, when on personal time—is “unclear, it’s like playing a game of Clue,” Morrow said. “The really unfair part is that for union members, who are federal employees, their boss is the president,” unlike in the corporate world, Morrow said.

Conway’s conduct, more “egregious” than any he’s seen by a federal employees, “does show the unfairness that merit system employees can be fired but political appointees can violate the law at their leisure, and nothing happens to them,” Morrow said.

Perhaps there should be new penalties for political appointees, he added, so that the Justice Department could prosecute them.

Gaps in Enforcement Powers

Debra Roth, managing partner at Shaw Bransford & Roth, agrees that the OSC’s report on Conway highlights gaps in its enforcement powers that could prompt changes in the law by Congress.

At a June 26 House Oversight and Reform Committee hearing, just such a bill was announced by Rep. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., after she cited a Trump appointee at the Housing and Urban Development Department who said she no longer cared about the Hatch Act. The “Presidential Appointee Accountability Act” (H.R. 3499) would require the president to respond to OSC recommendations within 30 days and threaten politically appointed employees found to have violated the act with $10,000 fines.

Roth said she would be surprised if courts agreed with the claim by the White House and Conway that her on-camera and online statements are protected by the First Amendment. In Trump’s favor, however, many Hatch Act specialists consider the letter from the OSC calling for her firing to be highly unusual, Roth said, which was written in part because her conduct was unusual.

Overall, the OSC’s Hatch Act Unit “does an extraordinary job trying to stay in touch with changes in how the workforce uses social media to discuss political issues and historically has applied the law evenhandedly,” Roth said, in an era when political engagement has moved from “literally the water cooler” to the instant communication of social media.

Early in the Trump administration, OSC took the position that Trump was already running for reelection, she noted. Kerner’s admonition that the Trump team is “setting a bad example” is realistically all Kerner had to go with, given his lack of enforcement powers over political appointees, she said.

“But setting a good example is not the agenda for this administration. It’s not important to them,” so they are ignoring norms in multiple areas, "which shows gaps in the law,” Roth said.

But Roth sees a larger issue beyond the rule of law. “It’s about whether we as Americans still believe in an executive branch work force that’s apolitical. It’s a conversation that’s been brewing for about eight years,” she said.

A White House “can have its political team out there campaigning, they just have to use a different source of money to fund those people’s salaries,” Roth added. “There’s an equity for taxpayers too. What about the taxpayer who doesn’t support the political views of this administration? Part of the Hatch Act is keeping the functioning of government apolitical so that all Americans have confidence the system is working for all.”