Xiao Fang/Wikimedia Commons

Visiting National Parks Could Change Your Thinking About Patriotism

Patriotism means pride in country, but what are we proud of? A former national park ranger suggests that visiting historic sites can remind Americans of the heritage, good and bad, that they share.

When I took a post-college job as a seasonal ranger at Grand Teton National Park 23 years ago, I noticed right away that my “Smokey Bear” hat carried some serious emotional baggage. As I later wrote in my book, “Reclaiming Nostalgia: Longing for Nature in American Literature,” park visitors saw the hat as an icon of tradition and romance, a symbol of a simpler era long gone.

For many Americans the physical grandeur of parks like Grand Teton, Yosemite and Yellowstone also inspires patriotic pride. Twenty-first-century patriotism is a touchy subject, increasingly claimed by America’s conservative right. But the national park system is designed to be democratic – protecting lands that belong to the public for all to enjoy – and politically neutral. The parks are spaces where love of country can be shared by all.

But some sites send more complex messages. In my new book, “Memorials Matter: Emotion, Environment, and Public Memory at American Historical Sites,” I explore how patriotism plays out at sites where education, not recreation, is the priority. To research it I visited seven memorials to see how their structures and natural landscapes inspire patriotism and other emotions.

For me, and I suspect for many, national memorials elicit conflicting feelings: pride in our nation’s achievements, but also guilt, regret or anger over the costs of progress. Patriotism, especially at sites of shame, can be unsettling – and I see this as a good thing. In my view, honestly confronting the darker parts of U.S. history as well as its best moments is good for tourism, for patriotism and for the nation.

Whose History?

Patriotism has roots in the Latin “patriotia,” meaning “fellow countryman.” It’s common to feel patriotic pride in U.S. technological achievements or military strength, but Americans also glory in the diversity and beauty of our natural landscapes. That kind of patriotism, I think, has the potential to be more inclusive, less divisive and more socially and environmentally just.

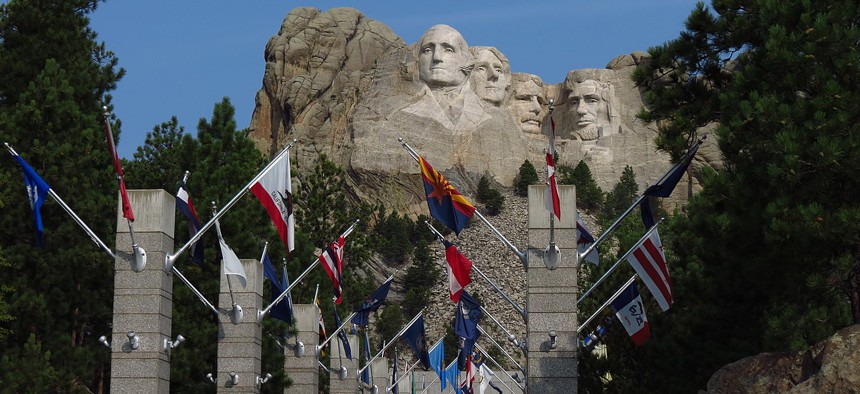

National memorials can summon more than one kind of patriotism. Take Mount Rushmore, which was designed explicitly to evoke national pride. Tourists walk the Avenue of Flags, marvel at the labor required to carve four U.S. presidents’ faces out of granite and applaud when rangers invite military veterans onstage during visitor programs. Patriotism at Rushmore centers on labor, progress and the “great men” that the site describes as founding, expanding and defending the U.S.

But there are other perspectives. Viewed from the Peter Norbeck Overlook, a short drive from the main site, the faces of Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt and Lincoln are tiny elements embedded in the expansive Black Hills region. The Black Hills were and still are a sacred place for Lakota peoples that they never willingly relinquished. Viewing Mount Rushmore this way puts those rock faces in context and raises questions about history and justice.

Mt. Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota, viewed from the Peter Norbeck Overlook. Jennifer Ladino, CC BY-ND

Some national monuments conduct reenactments to help visitors relive the past and feel a sense of history and authenticity. At Golden Spike National Historic Site in Utah, tourists can view replica steam locomotives and watch a reenactment of driving the spike that completed the first transcontinental railroad.

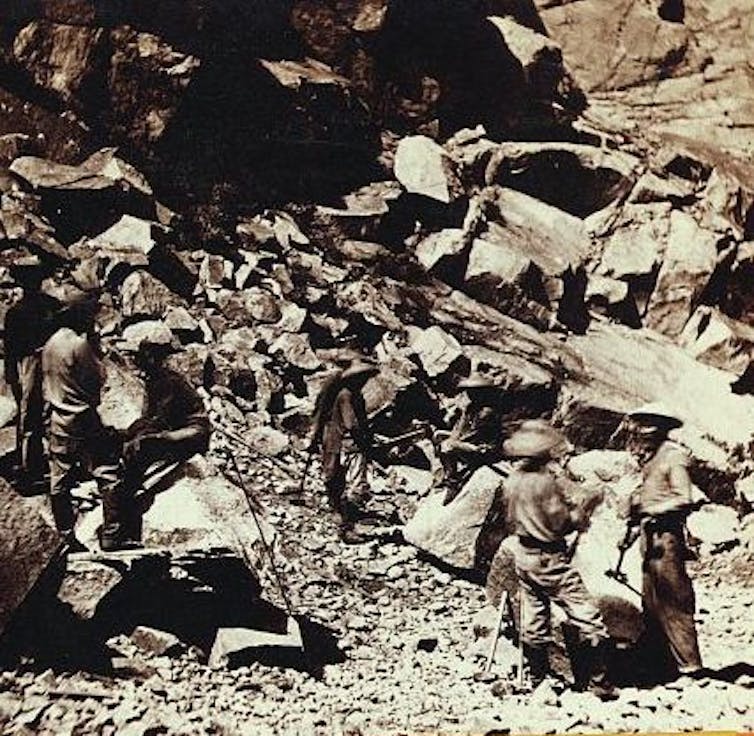

This park also ties patriotism to technology, labor, unity and progress. But it downplays countless lives lost during construction, including a disproportionate number of Chinese laborers. There’s an implied whiteness to the patriotism here, although those Chinese workers are receiving belated recognition.

Away from the main complex, however, visitors can see an impressive natural landscape carved by geologic forces. At “Chinaman’s Arch,” they can read about ancient Lake Bonneville, which once covered 20,000 square miles. Against the backdrop of geologic time, human labor and technological power look less impressive. A different feeling of patriotism emerges here that can embrace the physical country all Americans share.

Chinese railroad workers in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains, photographed between 1865 and 1869. Alfred Hart/Library of Congress

Sites of Shame

Even sites where visitors are meant to feel remorse leave some room for patriotism. But at places like Manzanar National Historic Site in California – one of 10 camps where over 110,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II – natural and textual cues prevent any easy patriotic reflexes.

Reconstructed guard towers and barracks help visitors perceive the experience of being detained. I could imagine Japanese-Americans’ shame as I entered claustrophobic buildings and touched the rough straw that filled makeshift mattresses. Many visitors doubtlessly associate mountains with adventure and freedom, but some incarcerees saw the nearby Sierra Nevada as barricades reinforcing the camp’s barbed wire fence.

Rangers play up these emotional tensions on their tours. One ranger positioned a group of schoolchildren atop what were once latrines, and asked them: “Will it happen again? We don’t know. We hope not. We have to stand up for what is right.” Instead of a self-congratulatory sense of being a good citizen, Manzanar leaves visitors with unsettling questions and mixed feelings.

Young tourists experience the humiliating lack of privacy at Manzanar National Historic Site. Jennifer Ladino, CC BY-ND

Humble Patriotism

Visiting and writing about these sites made me consider what it would take to recast patriotism as collective pride in the United States’ diverse landscapes and peoples. I believe one essential ingredient is compassion. Recent controversies over Confederate monuments showed that many Americans were unwilling to imagine how public memorials could be offensive or traumatic for others.

Greater clarity about value systems can also help. Psychologists have found striking differences between the moral frameworks that shape liberals’ and conservatives’ views. Conservatives generally prioritize purity, sanctity and loyalty, while liberals tend to value justice in the form of concerns about fairness and harm. In my view, patriotism could bridge the apparent gap between these moral foundations.

My research suggests that visits to memorial sites are helpful for recognizing our interdependence with each other, as inhabitants of a common country. In her recent book, “The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks,” Terry Tempest Williams wonders, “What is the relevance of our national parks in the twenty-first century - and how might these public commons bring us back home to a united state of humility?” Places like Manzanar and Golden Spike are part of a common heritage embedded in public lands. It’s our responsibility as citizens to visit these places with both pride and humility.

![]()

This post originally appeared at The Conversation. Follow @ConversationUS on Twitter.