EPA headquarters in Washington. Rob Crandall/Shutterstock.com

EPA Exceeded Trump’s Deregulatory Expectations

But the agency’s inspector general says officials shortchanged management controls and haven’t been transparent about decision making.

The Environmental Protection Agency has surpassed the Trump administration’s goals for rolling back regulations, however in doing so the agency bypassed important management controls, EPA’s inspector general found.

Shortly after Inauguration Day in 2017, Trump issued two executive orders to fulfill his campaign promise of reducing the regulatory burden many conservatives believe has been an impediment to economic growth. Executive Order 13771 required agencies to cut two regulations for every new regulation they introduced and Executive Order 13777 mandated that agencies establish a task force and designate an officer to implement the first executive order. EPA’s inspector general on Aug. 9 released a report that found the agency surpassed requirements for deregulation and savings goals in 2017 and 2018. However, the IG found that EPA’s deregulatory process lacked guidance, or management controls, and was not sufficiently transparent in its decision making.

Besides a March 2017 memo from then-Administrator Scott Pruitt that established a regulatory reform task force, the agency relied solely on two guidance documents from the Office of Management and Budget to implement the executive orders, according to the watchdog. In 2017, EPA saved $21.5 million by cutting 16 regulations and adding one new one; in 2018, the agency saved $75.1 million by cutting 10 regulations and adding three new ones. The regulations EPA cut resulted in the removal of various air quality standards, reduction in compliance standards for chemical safety, reduced public notice on sewer overflow into the Great Lakes and fewer reporting requirements for hazardous waste materials.

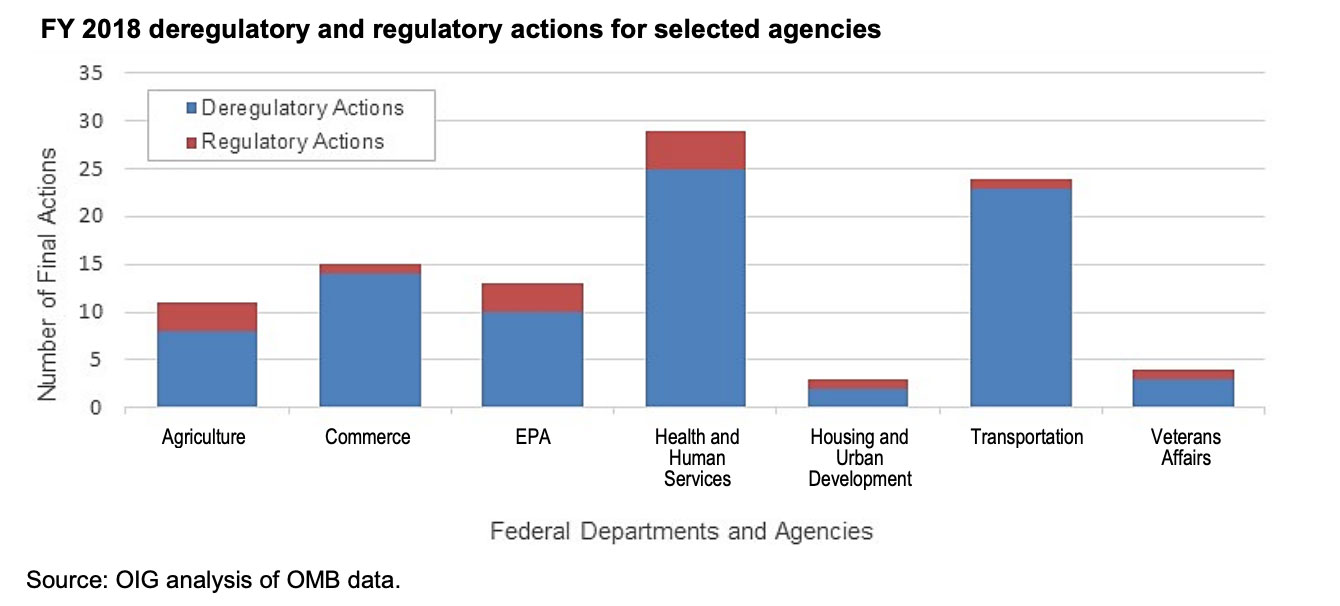

“The EPA’s success in exceeding the ‘two-for-one’ ratio is not unique” since several other agencies have also done so, the IG noted. In 2017, the Agriculture, Commerce, Homeland Security, Interior, Labor, Transportation, Treasury and Veterans Affairs departments all slashed regulations without adding any new ones. While some of those added new regulations in 2018, many still exceeded the administration’s deregulation goals.

The IG found several problems related to EPA’s transparency in how officials made their decisions. First, EPA only included two of the five required OMB performance indicators in its annual performance plan for 2019—the number of regulations and deregulations issued, and the cost savings associated with them—but did not report the number of evaluations to identify potential actions, deregulatory actions recommended by the task force and the number of regulations issued in response to the task force.

Secondly, the watchdog found it was difficult for the public to monitor regulatory actions since EPA’s website does not provide sufficient information. The executive order required a 90-day progress report, which the agency completed but did not make publicly available (only EPA’s political leadership had access to the document). Lastly, some staff members did not know about the status of executive order recommendations or were not given feedback on regulatory or dereulgartory actions they proposed.

In regards to stakeholder outreach, Pruitt’s March 2017 memo called for offices involved with the executive order to reach out to external stakeholders and provide the feedback to the task force. However, the inspect general reported, “Program offices were not explicitly instructed to continue this activity in subsequent years” and the agency “has not specified whether stakeholder feedback meetings should be repeated.” In speaking with staff members, the auditors found they wanted to continue getting feedback from outside groups but were not asked to do so. The watchdog also discovered there was no schedule for task force meetings and no timeline of future progress reports.

The IG recommended EPA specify in the task force guidance the frequency of meetings, means of publicly sharing progress reports and regulatory/deregulatory recommendations, and the frequency and means of stakeholder outreach. It also recommended that EPA establish a portal to provide updated information on actions related to Executive Order 13771.

EPA agreed generally with the first recommendation and provided some individual plans of action, but, “did not provide corrective actions that would update the task force guidance,” according to the IG. The agency disagreed with the second recommendation because it believes it already makes the information related to the executive order public through the Semiannual Regulatory Agenda. The inspector general pushed back and said since this report is for all federal agencies and is only updated twice a year, it is not sufficient.

EPA under the Trump administration has been under intense scrutiny for its regulation rollbacks, dismissal of scientists and political interference in agencies’ science work. At EPA, “Decisions for the most part are made without consulting or seeking advice from long-time experts,” Jeff Ruch, executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, told Government Executive.

When Andrew Wheeler was confirmed as EPA administrator in February, The New York Times reported, “Republicans said they have been delighted to discover Mr. Wheeler is as enthusiastic about repealing environmental regulations and promoting coal as Mr. Pruitt was, and are looking to him to cement Mr. Trump’s legacy as a warrior against what they see as regulatory overreach.” Despite internal pushback from career employees and recent increase of inquiries into the EPA’s science integrity office, EPA is still generally succeeding with the directives from the president, the Times reported.

The inspector general conducted the audit from May 2018 to May 2019. It reviewed agency guidance documents, policies and related executive orders as well as spoke with EPA staff and external stakeholders. Stakeholders included: the Agriculture and Health and Human Services dDepartments, Agriculture Department, the nonprofit Earthjustice and Columbia Law School’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.