Rob Crandall/Shutterstock.com

Distrust, Staffing and Funding Shortages Imperil Election Security

The federal government has made improvements since 2016, but ultimately, it may not be enough.

Special Counsel Robert Mueller was emphatic when he testified before the House Intelligence Committee on July 24 about Russian interference in the 2016 election: “It wasn’t a single attempt. They’re doing it as we sit here, and they expect to do it during the next campaign.”

In an earlier, less partisan era, Mueller’s warning likely would have galvanized lawmakers and propelled them to action to ensure the security and integrity of American elections. While federal agencies have taken critical steps to improve security around U.S. elections since 2016, those efforts have been hampered by inadequate funding; staffing problems; mixed messages from Congress and the administration; and, not insignificantly, by Constitutional questions—states and localities hold primary authority for administering elections, and some Republicans worry about the federal government usurping state powers in the name of security.

But the special counsel’s warning had no such galvanizing effect. Hours after Mueller testified in the House, Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith, R-Miss., blocked, without giving a reason, election security bills in the Senate, one of which would have required campaigns to alert the FBI and the Federal Election Commission about election assistance offers from foreign countries. The next day, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., denied the Democrats’ request for a vote on the House-passed Securing America’s Federal Elections Act, which would have authorized $775 million to bolster state election systems and required paper ballots as a guard against vote tampering.

McConnell said the legislation, which passed the House with just a single Republican vote, would nationalize election authorities that “properly belong to the states.”

While few things are more fundamental to democracy than the integrity of the election system, finding a bipartisan consensus for ensuring that integrity has been elusive, and as a result, agencies’s efforts are far less effective than they could be otherwise.

The Federal Role

The federal players with roles in election security are many: the Homeland Security and Justice departments have components focused explicitly on election security; the intelligence community and Defense Department track foreign threats and defend networks from foreign attack; the independent Election Assistance Commission certifies voting systems and serves as an information clearinghouse for best practices in election administration.

In January 2017, after the FBI determined that hackers had exfiltrated data from some state election systems, the Homeland Security Department gave election systems the designation of critical infrastructure. Under federal law, the designation applies to assets for which “incapacity or destruction . . .would have a debilitating impact on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination.”

“We went from being very reactive in the incidents that occurred in 2016 to . . . a more proactive environment where all 50 states are engaged with us,” said Geoff Hale, program manager of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, which was established in November 2018. CISA works with other federal agencies, through the Elections Infrastructure Information Sharing and Analysis Center, a component of the Government Coordinating Council formed in March 2018, to share information across all levels of government—federal, state, local and tribal.

More than 18,000 local justifications are taking advantage of the free services CISA offers to help detect and recover from foreign threats. CISA currently has over 500 employees working on election security, according to the agency’s “strategic intent” document released in August.

"By the end of 2017 and early 2018 [Homeland Security] really invested in learning the field and learning how to communicate with us and so you see now it's really a much more collaborative relationship,” said Amy Cohen, executive director of the National Association of State Election Directors. She said these efforts paid off in the 2018 midterms and believes such progress will continue.

The key player in understanding foreign threats is the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. In mid July, then National Intelligence Director Dan Coats established a new position of election threats executive to coordinate all IC election security activities and tapped Shelby Pierson, an intel veteran with two decades of experience, for the role. Pierson served as the DNI’s crisis manager for election security during the 2018 midterm elections.

But nine days later, on July 28, President Trump, who has repeatedly questioned intelligence assessments of Russia’s role in election interference, announced that Coats would step down. Trump initially said he would replace Coats, a widely-respected national security stalwart, with Rep. John Ratcliffe, a Texas Republican and Trump loyalist with scant intelligence experience. Ratcliffe’s lack of experience and skepticism that Russia had interfered in the 2016 election to help Trump bothered some Senate Republicans, whose votes he would have needed for confirmation, and he eventually withdrew from consideration.

Before leaving office, Coats directed all intelligence offices involved in election security to identify a senior leader who will work with Pierson to ensure coordination and prioritization of efforts. He also created an executive board to “serve as the principal vehicle for IC-wide coordination and focus on election threats” with other agencies.

When foreign threats are detected, it falls to the Justice Department to investigate them and enforce federal election laws. “It took some time to understand, through our investigations, what new threats we are facing and what policies and procedures we need to respond to them,” Deputy Assistant Attorney General of the National Security Division Adam Hickey said.

The department has taken a number of steps to deal with the threat: It established the attorney general’s Cyber-Digital Task Force and the FBI’s Foreign Influence Task Force, and briefed election officials on the challenges in all 50 states. Department officials are also exploring whether new laws are needed to combat internet propaganda. “Like any intelligence puzzle, we learn more information over time,” said Hickey, on the department’s hindsight on vulnerable election counties. He hopes that “election supervisors, whether they’re at the state level or the county level, have confidence that they can trust the FBI” and report any problems they encounter.

Unlike other agencies, the Election Assistance Commission’s sole focus is elections. This independent and bipartisan commission was established to implement the 2002 Help America Vote Act, but it has been woefully understaffed and underfunded for the mission. In fiscal 2018, the commission received $380 million to help states and localities with their election infrastructure and administration. It was the first time since 2010 that Congress made resources available through Help America Vote to support federal election improvements, the commission noted in its grant expenditure report for 2018.

To prepare for the 2020 elections, EAC is offering technology training to election officials, testing and certifying voting systems, helping states use their appropriated funds to beef up security, and improving communication with other federal agencies, Chairwoman Christy McCormick and Vice-Chair Ben Hovland outlined in July. The commission is also updating voting system guidelines to reflect technology and security developments.

“There is no shortage of ambition at EAC when it comes to supporting this work, but there is a stark shortage of funds for such activities,” the EAC commissioners wrote in a joint statement to the Senate Rules and Administration Committee in May. With a staff of 22, the commission has fewer than half the number of employees it had in 2010. As a result, the commission does not have full-time staff devoted to key security initiatives and is unable to develop a cyber assistance unit that many state and local jurisdictions have requested.

Major Challenges

The political dysfunction that hinders many agencies is keenly felt at the Election Assistance Commission, which has survived multiple attempts by House Republicans’ to terminate it altogether. Politico reported in June allegations that EAC Director Brian Newby has tried to dismantle the agency from within. Former employees and others who work with the EAC told Politico he, “blocked important work on election security, micromanaged employees’s interactions with partners outside the agency and routinely ignored staff questions.”

Newby dismissed Politico’s reporting in an op-ed in The Hill on July 2: “Recent reports have been more politically-driven and sensational than fact-filled and productive.” He outlined the commission's “multifaceted approach to helping election officials strengthen election security” and said, “Members of Congress repeatedly note the EAC’s new-found sense of purpose and vital mission.”

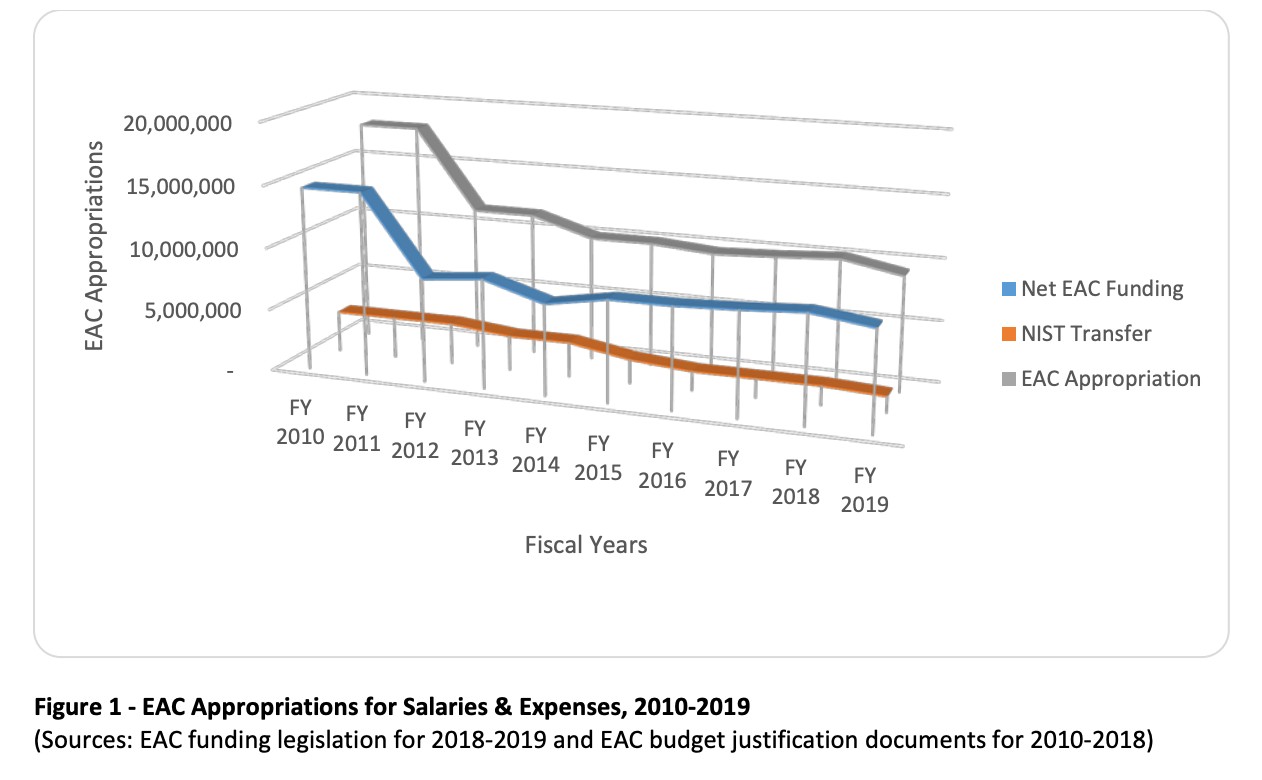

Newby’s characterization is hard to square with the EAC inspector general’s recent report on the commission’s strategic plan, which notes the disconnect between the commission’s expanding role and diminishing resources: EAC’s budget for salaries and administration has declined from a high of $18 million in 2010, to just $8 million in 2019. The chart below shows EAC’s appropriations, including legislatively mandated transfers to the National Institute of Standards and Technology, from fiscal years 2010-2019.

The commission also has struggled to maintain a quorum of three. Since the first four commissioners were confirmed in December 2003, the EAC has had a quorum just 68% of the time, according to the Bipartisan Policy Center. As of January 2019, it now has a quorum.

An aide on the House Administration Committee, which oversees federal elections, echoed the concerns about the commission’s low morale, staffing problems and fluctuating quorum: “It’s difficult to be an agency when for the longest time the Republicans were just trying to get rid of them. There was no oversight at all for about eight years, while the Republicans were in the majority,” the aide said.

Homeland Security has also struggled with its election security role. The department inspector general’s semiannual report, published in May, found it “has not completed plans and strategies critical to identifying emerging threats and mitigation activities, and to establish metrics to gauge progress in securing the election infrastructure.” The watchdog identified senior leadership turnover, lack of administrative staff, a long security clearance process, and distrust from state and local officials as roadblocks to accomplishing election security objectives. It recommended that DHS hire more staff to help with technical assistance and outreach to state and local governments as well as improve its patch management to secure information systems, as required by the 2014 Federal Information Security Modernization Act.

The same watchdog reported in February that the department’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency did not have dedicated staff focused on securing election infrastructure. “Our interviews with six cybersecurity advisors and eight regional directors for the protective advisors disclosed concerns that CISA is not adequately staffed to provide support to state and local election officials,” the IG reported.

At the Justice Department, an ongoing challenge is respecting the authority and privacy of states and localities even when the public wants more information. It’s, “an aspect of the landscape that we in law enforcement at the federal level have to wrestle with,” Hickey said. If the FBI identifies localities where election interference has occurred without their consent, it would create “an extraordinary disincentive to call us voluntarily.”

That, in a nutshell, is one of the biggest challenges federal agencies face. They can provide the assistance, but states must choose to accept it. “Elections are a state and local government function, so the federal government has to be cautious about respecting those boundaries. The work it’s doing is generally on a voluntary basis,” said Vijay D’Souza, director of the Government Accountability Office’s Information Technology and Cybersecurity team.

Structural Vulnerabilities

Darrell West, director of the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution, said other countries are taking the foreign interference threat much more seriously than the United States. West suggested the federal government provide states and localities with more technical assistance on fighting cyber threats and more money to upgrade their equipment.

Strategy Program Manager at United States European Command Jason Wechan wrote in a Pentagon white paper there is a, “lack of a coherent and unified whole of government effort” because the “democratic, federal system of government hinders the ability to effectively plan, coordinate and execute a comprehensive strategy across all federal government agencies.”

For example, federal agencies significantly improved network security after Homeland Security issued a binding operational directive in 2017 requiring the adoption of new email security measures. But the department cannot impose such requirements on state and local governments. Valimail, an internet security company, found only 1.3% of state and local domains have such protection. Dylan Tweney, Valimail vice president of communications, said, “I know that that’s a political football how much oversight the federal government has in election infrastructure.”

Another aspect of a decentralized election system is the variation among voting machines. VICE’s Motherboard published a recent investigation that found that about three dozen election systems in 10 states have been connected to the internet over the last year, in many cases without the knowledge of election officials. “For security reasons, the [Secure File Transfer Protocol] server and firewall are only supposed to be connected to the internet for a couple of minutes before an election to test the transmission, and then for long enough after an election to transmit the votes,” VICE reported. The research didn’t conclude the machines were hacked, but showed how little election officials sometimes know about their equipment.

During a speech at the annual hacking conference DEFCON, Christopher Krebs, CISA director, said, “When you put a local jurisdiction in the far-flung regions of the upper peninsula of Michigan facing the Russian GRU [military intelligence service] threat ... that's not a fair fight,” Dark Reading reported.

Some of the country’s largest voting machine vendors signaled a willingness to establish a coordinated vulnerability disclosure program during a forum hosted by EAC in August. A challenge for such a program in the election industry, however, is aligning with the federal and state testing and certification process and avoiding long, complicated and expensive situations, Cyberscoop reported.

EAC’s Newby maintains that the decentralized voting system “provides a fabric of security” because it makes it more difficult for “a foreign interference to attack 8,000 different vector points.” The disadvantage is that some states and localities will not have adequate security. A Politico national survey of election offices found that many counties don’t have enough money to upgrade voting machines and some county officials want to keep their existing ones because of familiarity and convenience, despite potential security risks.

President of the National Association of State Election Directors Keith Ingram said federal funding should be on a more “sustainable and predictable” basis, so that states and localities “could sort of plan around [it] instead of these one-time dumps of money.”

Both parties agree that election security shouldn’t be a partisan issue, however, they can’t come to a consensus on how to go about it. A Pew Research Center study from October 2018 found broad partisan mistrust of the opposite party’s commitment to election security. Of those surveyed, 64% of Democrats and 56% of Republicans believed the opposing party had little to commitment to fair and accurate elections. It also found that among those who thought Russia or other governments would try to interfere in the election, Democrats were more likely than Republicans to say this was a major issue.

That distrust may turn out to be the greatest roadblock to securing U.S. elections.

Image via Rob Crandall/Shutterstock.com.

Correction: An earlier version of this story said the Election Assistance Commission received $3.6 billion to help states and localities with their election infrastructure and administration in 2018. States and localities actually received $380 million last year. States and localities have received $3.6 billion in federal funds since the Help America Vote Act was signed into law in 2002.