C-SPAN

Trump Interior Nominee Fast-Tracked a ‘Deficient’ Drilling Permit

Oil lobbyists’ answer to regulatory roadblocks is “We’ll call Kate” – as in Kate MacGregor, nominee for the No. 2 job at Department of the Interior.

This story was originally published by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization based in the San Francisco Bay Area. Learn more at revealnews.org and subscribe to the Reveal podcast, produced with PRX, at revealnews.org/podcast.

In March 2017, a politically connected oil firm called Cimarex Energy Co. was in a hurry to begin fracking on a flat expanse of farmland in the western Oklahoma oil patch.

But the company’s application for a federal drilling permit had been rejected as “incomplete” and “deficient,” records show. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management had flagged both engineering and environmental issues. The company faced a 60-day wait while a revised application was being reviewed.

Cimarex didn’t want to wait. Instead, the company called its lobbyists.

In the days that followed, political appointees at the highest levels of the U.S. Department of the Interior went to extraordinary lengths to fast-track Cimarex’s drilling permit, according to a trove of emails reviewed by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting.

Among the officials moving to expedite the permit: Katharine MacGregor, then an up-and-coming aide to then-Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke. President Donald Trump recently nominated her to the powerful No. 2 post at the Interior Department, an agency that supervises hundreds of millions of acres of national parks and public lands, including their use for energy production. Her confirmation hearing is set for Tuesday.

Records of the Cimarex permit show that in the Trump era, federal officials eager to carry out the president’s “American energy dominance” agenda sometimes have reached far down into the bureaucracy to assist developers in sidestepping regulatory hurdles.

According to the emails, Cimarex took its Oklahoma permit problem to the Independent Petroleum Association of America, an influential Washington-based industry lobby whose former lawyer, David Bernhardt, is now secretary of the interior.

A petroleum association lobbyist then turned to MacGregor for help.

From her years as a Republican staffer to the House Natural Resources Committee’s Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources, MacGregor already was well known as a friend of the energy industry: In recorded remarks at a June 2017 meeting, the association’s political director quipped that once MacGregor joined the Department of the Interior in January, “We’ll call Kate” became the association’s default solution to regulatory roadblocks.

In this case, MacGregor delivered, taking Cimarex’s problem to the top, bypassing layers of civil service expertise to approach Michael Nedd, then acting head of the 10,000-employee Bureau of Land Management – the Interior Department agency in charge of energy development on federal land. Six other high-level department officials also were looped in.

The next day, Nedd reported that an “expedited review” of Cimarex’s permit was underway. Sixteen days after Cimarex complained to the petroleum association, it had its permit.

The Interior Department has 70,000 employees, a $15 billion budget and vast responsibilities: managing 500 million acres of public lands, overseeing federal water projects and interacting with Native American tribes. Through the BLM, it also supervises 41,000 energy leases and 94,000 active oil and gas wells on federal land.

Jesse Prentice-Dunn, policy director for the Center for Western Priorities, a conservation group, said it was astonishing that top officials at such a large and complex agency spent time ironing out Cimarex’s problems with a single permit.

“This just is not how the process is supposed to work,” he said. He noted that career professionals, not political appointees in Washington, are charged with reviewing applications and issuing drilling permits.

“It sounds like they think their job is customer service for the oil industry,” he said of the senior political appointees who intervened.

Complaints of political and corporate interference have been rife at the Interior Department since Trump took office, a recent survey of 16 of the department’s most senior career employees indicates.

The survey, conducted by the Washington, D.C.-based Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, found that career staffers blame the department’s political appointees for imposing a culture of what one called “politically driven micromanagement.”

In response to a query from Reveal, a department spokeswoman said the department has followed “all laws, rules and regulations regarding permits” since Trump took office. She acknowledged the department is keen to act on drilling permits.

“Since day one, the Department has prioritized improving the overall permitting process to tackle longstanding backlogs and delays,” she wrote in a statement. Drilling permits on average now are processed in 108 days, down from more than 200 days under the Obama administration, she noted.

The spokeswoman did not respond to Reveal’s specific questions about Cimarex or its request to interview MacGregor and Nedd.

Cimarex declined comment. The Independent Petroleum Association of America did not respond to requests for comment.

The emails about the Cimarex permit were among Interior Department documents obtained through a public records request by two good-government groups, Documented and Public Citizen.

‘We’ll call Kate’

MacGregor, the official who sped through the Cimarex permit, is a 36-year-old former Republican congressional aide. While a senior staffer of the House Committee on Natural Resources, she developed strong ties to the energy industry and its lobbyists. In recent years, she has also built a public profile as an advocate of offshore oil drilling and a foe of any environmental rules that might limit energy production.

In a 2015 panel discussion at a conference of the Alabama Natural Gas Association, she said she was “really excited” about industry-backed bills that would have allowed natural gas pipelines to be built across national parks. The measures were not enacted.

After Trump’s inauguration, MacGregor quickly went to work for Zinke at the Interior Department.

In congressional testimony and on Fox News, she has promoted Trump’s “energy dominance” program, which has entailed substantial rollbacks of a long list of regulations designed to mitigate the environmental impact of fossil fuel production.

When the Interior Department in June 2017 put rules on hold that aimed to limit the discharge of methane gas from federal oil fields – a driver of global warming, according to climate scientists – MacGregor defended the rollback, arguing that the rule had imposed a “significant regulatory burden” on the oil industry.

She was at the forefront of the administration’s controversial plans to open up coastal waters off Florida, California and Alaska for oil development, telling Congress in July 2017 that offshore drilling would “secure American energy dominance, create jobs, lower costs for working Americans and build a strong economy.”

And, as Pacific Standard magazine reported, after MacGregor met repeatedly with coal executives in 2017, she successfully pushed to shut down a government-funded study of the public health dangers of mountaintop strip mining. The industry had denounced the study as “anti-coal.”

At the Interior Department, MacGregor quickly became known as a go-to staffer for energy companies seeking regulatory relief – as is made clear in a recording from the June 2017 meeting of the Independent Petroleum Association of America at a beachfront Ritz-Carlton resort in Southern California.

Reveal previously reported that oil executives at the meeting boasted of their close relationship to Bernhardt, the group’s former lawyer, who then had recently been named to the No. 2 post at the Interior Department, the position MacGregor might soon occupy. Trump named Bernhardt interior secretary in March after Zinke resigned amid an ethics scandal.

In other remarks at the meeting, which have not been reported previously, Dan Naatz, the petroleum association’s political director, portrayed MacGregor as a reliable friend of the industry.

“I’m sure half the people in this room know Kate MacGregor – she worked on House Resources Committee,” Naatz told the group. “She is over at Department of Interior doing a great job.”

Then he described a conversation with the Western Energy Alliance, another oil and gas lobbying group, about MacGregor.

“I was on a call a couple days ago, and I finally started to laugh because it was Western Energy Alliance,” he said. “And there were a number of issues that came up and they said, ‘We’ll call Kate.’ Next issue: ‘Well, we’ll call Kate.’ Next issue: ‘Well, we’ll call Kate.’

“And I said, ‘Kate is one person, guys, she can’t do all that.’ And they said, ‘Well, we know Kate well.’ ”

It wasn’t just the Western Energy Alliance that had her on speed dial. Naatz said MacGregor had told another petroleum association lobbyist that she was being flooded with special requests.

“She said, ‘Well, I’ve got 130 issues that have started to come up, and all you’ve done is add five more to my list,’ ” Naatz said.

The Cimarex lease illustrates just how responsive MacGregor could be to an urgent industry request.

A problem in the oil patch

Cimarex, a $2.3 billion oil and natural gas company based in Denver, specializes in hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, in the Southwest. Its watchwords are “profitability, safety and environmental responsibility,” CEO Thomas Jorden says. But Cimarex has attracted scrutiny from regulators and conservationists.

In 2007, Cimarex encountered fierce criticism when it moved to drill for gas near New Mexico’s Chaco Culture National Historical Park. Preservationists feared the project would damage the park’s famed archeological ruins. After lawmakers threatened to intervene, the company abandoned the plan.

In 2009, the Interior Department accused Cimarex of interfering with a government audit of the company’s royalty payments on federal energy leases. Cimarex paid a penalty of $327,000 for royalty violations, records show.

In 2017, Cimarex was fined $68,000 for illegally dumping 18,000 barrels of oilfield wastewater into a tributary of the Pecos River in West Texas, records show. James Amos – then an engineer with the BLM’s Carlsbad, New Mexico, field office – warned at the time that the spill could have “devastating” effects on the Delaware River, saying, “It’s going to have a major impact on any aquatic life in there.” Earlier this year, environmental group Earthworks filed a complaint with state regulators about air pollutants that appeared to be spewing from a leaky Cimarex oil storage facility in New Mexico.

Jorden portrays Cimarex as a cautious political player. At a 2018 conference, he said he “really welcomed” Trump’s aggressive rollbacks of energy regulations, but worried about backlash.

The energy industry should “make sure that our environmental footprint is minimized,” he said. Otherwise, “President Elizabeth Warren will make us regret it,” he said, referencing one of the leading Democratic candidates for the 2020 presidential race.

At the time of Trump’s election, Cimarex was coming off two dreadful years in which it had lost nearly $3 billion, mostly because of a worldwide collapse in energy prices. As prices began to rebound in the fall of 2016, Cimarex sought BLM permits to drill on federal land in Oklahoma.

The application that hit a snag concerned 400 acres of farmland in the oil-rich Anadarko Basin near the South Canadian River in rural Grady County, 70 miles southwest of Oklahoma City. According to the records, a company controlled by Texas oil tycoon T. Boone Pickens first drilled for oil on the site in 1981. Production ended a decade later, and the BLM oil and gas lease changed hands several times after that.

In November 2016, Cimarex applied for a permit to drill a 22,000-foot-deep well for fracking – meaning the company would pressure-inject water and chemicals into the well in order to break up rock and release natural gas. Work was to get underway in February 2017.

But on Jan. 31, the BLM rejected Cimarex’s application.

Cimarex’s plan for preventing blowouts – an uncontrolled release of oil that can cause fires and explosions and risk injuring or killing oilfield workers – wasn’t adequate, the BLM said. Nor had the company sufficiently described how groundwater would be protected from contamination during drilling and production. Cimarex’s fracking fluid for this project would contain hydrochloric acid and other toxic chemicals, according to FracFocus, the national hydraulic fracturing chemical registry.

The geologic workup, which would flag seismic risks, was incomplete as well.

Within days, Cimarex updated its application to address the BLM’s concerns. But then new snags developed. An environmental assessment by the BLM’s Oklahoma field office hadn’t yet been reviewed by higher-ups, records show.

Also, the drilling site was in a region that for centuries had been inhabited by the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa and other Native American tribes. By law, the BLM was required to prepare a report on the area’s archeological resources and seek comment from the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs and each of the 11 affected tribes. The permit would be delayed at least 60 days while the BLM reviewed the environmental assessment and consulted the tribes, the BLM’s Oklahoma office wrote on March 8.

An energy lobbyist gets results

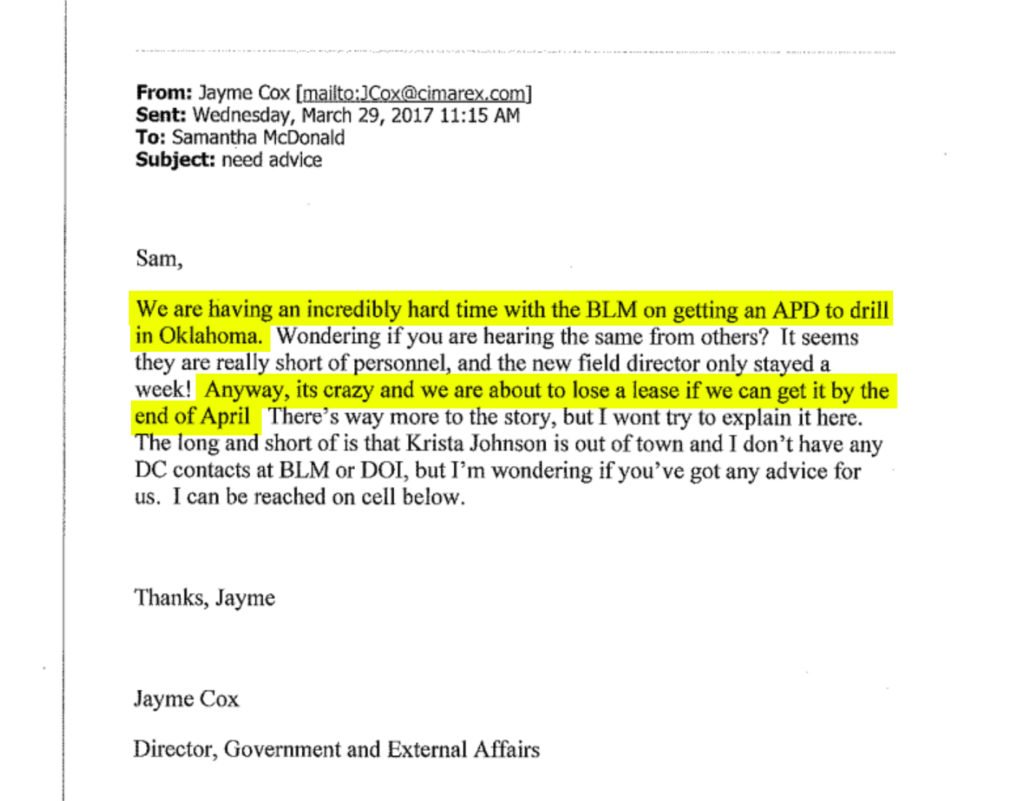

On March 29, Jayme Cox, Cimarex’s government affairs chief, sought help from Samantha McDonald, a lobbyist for the petroleum association.

“We are having an incredibly hard time with the BLM getting an APD to drill in Oklahoma,” Cox wrote by email, using the acronym for “application for permit to drill.” “It’s crazy and we are about to lose a lease if we can (not) get it by the end of April,” she wrote.

Actually, the problem had nothing to do with the BLM oil and gas lease.

Instead, records show, Cimarex was worried it might violate an agreement the company had made with the landowners to begin drilling by April 30, 2017. At any rate, Interior Department officials didn’t question Cimarex’s urgency.

McDonald forwarded Cimarex’s complaint to MacGregor and Kathleen Benedetto, a former mining industry advocate who was a senior adviser inside the BLM. The lobbyist asked for help and repeated the claim that Cimarex’s lease was in jeopardy. She also congratulated the officials for their work on a Trump executive order, issued the previous day, that ordered government agencies to suspend or rescind any federal rules “that unnecessarily encumber energy production.”

MacGregor then took the problem to Michael Nedd, who had been named acting BLM director only three weeks before.

In announcing the promotion, Zinke, then interior secretary, had called Nedd “an energy guy” and said the department was now “in the energy business.” Nedd responded quickly to Cimarex’s request.

He emailed Amy Lueders, then director of the BLM office in Santa Fe, New Mexico, which is responsible for managing 13.5 million acres of federal land in New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas and Kansas. Nedd wrote that “a few companies,” including Cimarex, “are concerned that BLM is unable to process their APDs due to staffing issues and their O&G (oil and gas) Lease may be at risk.”

Lueders marshaled her staff to solve Cimarex’s problem.

In emails to Washington, she wrote that the permit was delayed because some tribes hadn’t reviewed the archeology report, which said no sacred or prehistoric sites had been found in the area. Her staff would prod the tribes, she wrote, and she would have an aide reach out to update Cimarex. She urged Nedd to invite Cimarex to call her personally to “discuss specific concerns.”

Lueders’ assistant quickly began emailing the head of the BLM office in Oklahoma about Cimarex. And back in Washington, Benedetto assigned yet another official – a former director of the BLM’s California office then on special assignment in the capital – to help expedite the Cimarex approval.

At the field level, it was obvious what was wrong: Cimarex had cut the timing too close on the permit application.

As Scott McCorkle, a Bureau of Indian Affairs official, pointed out in response to a plea for help from Cimarex, the law gives tribes up to 30 days to review archeology reports, so they have an opportunity to dispute the findings and file an appeal. He said he had no ideas for how to speed up the statutory process.

“We have to let the time run,” he said.

On April 4, Nedd again wrote to MacGregor, reporting that Lueders was “on top of this issue” and was pushing the tribes for an “expedited review.”

Nine days later, the pressure paid off: Nedd reported that Cimarex was getting its permit the following day. The BLM office in Oklahoma had convened an “after action review” with Cimarex, he wrote, and was in “regular communication” with the company.

Meanwhile, with the BLM’s permission, Cimarex had begun construction at the well site even before the permit was approved. The company went ahead “to avoid lease expiration,” as the BLM’s Oklahoma office put it.

While the Cimarex issue was playing out, the petroleum association had a series of other contacts with MacGregor. On March 31, 2017, political director Naatz reached out to ask when the BLM would suspend the methane rule as Trump had ordered. On April 3, an association lobbyist asked MacGregor to meet with some visiting energy executives. “Sure,” she replied.

On April 24, another petroleum association official invited MacGregor to give a “closed door, off-the-record” presentation to the association’s “government affairs strategy group” – an audience of energy lobbyists.

A proposed topic was “how DOI (Department of the Interior) plans to reverse some of the damaging regulations from the prior administration.” MacGregor was interested. The department spokeswoman didn’t address whether MacGregor ultimately spoke at the event.

This story was edited by Esther Kaplan and copy edited by Nikki Frick.

Lance Williams can be reached at lwilliams@revealnews.org. Follow him on Twitter: @LanceWCIR.

![]()

This article was originally published in Reveal. It has been republished under the Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license license.

NEXT STORY: Government’s Pay System is Badly Fragmented