When Feeling American Requires Leaving America

For some Black U.S. diplomats, the moment they feel most American is when they are abroad.

Susan Page found home as a 14-year-old on a high-school orchestra trip to Europe. She wasn’t drawn to one place in particular. Rather, it was the feeling that, whether it be in London, Paris, or Amsterdam, she was meant to be an outsider. She would return overseas for her senior year of college, studying at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, before traveling to Italy during law school, and then on to Nepal for a postgraduate fellowship.

Eventually, she joined the U.S. State Department, representing her country around the world. Still, the feeling that struck her as a teenager on the other side of the Atlantic stayed with her: Only outside the United States did she—a Black woman, a diplomat—feel wholly American.

Page, who served in Kenya, Botswana, and Rwanda and became the first U.S. ambassador to South Sudan, had an experience familiar to many of her peers. Over the past year, I have spoken with several dozen female career diplomats while researching a book that will center these women’s experiences in modern American diplomacy. Some joined the Foreign Service during the civil-rights movement and the Cold War in the late 1960s, others began their careers just before 9/11, and a few are preparing for their first postings now. They have served in an array of places—from postwar countries such as Japan and France to conflict-wracked countries including Iraq and Yemen, as well as Russia, Guatemala, Micronesia, and elsewhere. For some Black diplomats, and in particular Black female diplomats I spoke with, traveling outside the U.S. and representing America to the rest of the world was the first time they felt they were treated like Americans.

As the U.S. once again wrestles—or attempts to avoid wrestling—with a legacy of racism and systematic discrimination, it’s instructive to reflect on this unique world, and the circumstances in which those who have been marginalized both feel truly American and best represent America. What can we learn from their experiences, and what is lost when they are turned away?

“It is only when I am overseas that I am truly and fully American,” Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley, the first woman to oversee the U.S. Consulate in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and a former ambassador to Malta, told me. “When I am in the Middle East or in Asia or even in Europe, I am seen as nothing but a U.S. diplomat.”

Were she to be identified by an unmarked photograph, Abercrombie-Winstanley said she could pass for North African or even Yemeni. “Until,” she told me, chuckling, “you see me move or open my mouth, and then you know I am American.” Though Abercrombie-Winstanley cautioned that not “everything was easy peasy, because racial and gender discrimination happens all over the world,” she nevertheless talked about that particular American exceptionalism that has always been both envied and mocked. She described it to me as “an exuberant profile and that Americanness, which is the same whether you’re white, Black, brown, or whatever.”

Yet it is precisely that point—that Abercrombie-Winstanley acknowledges she could “look” as though she is from elsewhere, but is the face of her nation abroad—that illustrates the tension inherent in the American diplomatic corps.

Much of a mid-career diplomat’s most visible work involves grip-and-grin photo opportunities with political counterparts or simply showing up to a D-Day commemoration. But these more mundane aspects of the job—being that face—underscore parts of the work that hold significant meaning. In France, former Ambassador Shirley Barnes remembers honoring World War II veterans during her time as the consul general in Strasbourg. “The French never saw me as a Black American but as the person the U.S. government had sent to represent its country.”

Perhaps even more confounding, then, is that the State Department has often failed to understand or embrace opportunities to meaningfully diversify its ranks, especially when it comes to Black women.

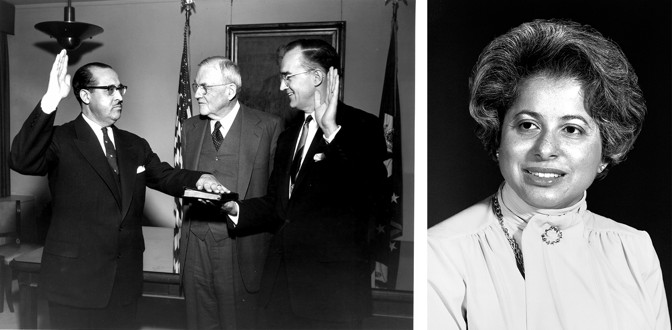

The first Black American to serve in the Foreign Service was Clifton Wharton, who joined in 1925, but he remained the U.S.’s only Black diplomat for the next 20 years. By 1949, just four other Black men had entered the Foreign Service. This disparity was even greater for Black women. In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Patricia Harris, a non-career official, as the U.S. envoy to Luxembourg, making her the first Black woman to become an American ambassador. It took another 25 years for Aurelia Brazeal to become the first Black female career diplomat to become an ambassador, when George H. W. Bush nominated her in 1990 to represent the U.S. before the Federated States of Micronesia. She went on to become ambassador to Kenya and Ethiopia.

In 1986, 257 of the 4,000 career Foreign Service officers, or 6 percent, were Black. Six of the country’s 150 ambassadors were Black, according to Equal Employment Opportunity Commission figures then cited by The New York Times. That same year, six Black Foreign Service officers filed a class-action lawsuit against the State Department for systematic racial discrimination. It came a decade after Alison Palmer filed a class-action suit, which was ongoing in 1986, on behalf of all women in the Foreign Service.

“Both of these lawsuits were indicators that there had been serious problems for people who were different from the traditional stereotype of a Foreign Service officer—Ivy League, white and male and possibly having a family member who had been a diplomat,” Pamela Spratlen, who joined the Foreign Service in 1990 and went on to become the U.S. ambassador to the Kyrgyz Republic and Uzbekistan, told me.

This dissonance between American ideals and the American reality, and how that plays out differently at home and abroad, is by no means unique to the Foreign Service. U.S. military veterans, themselves subjected to abuse and discrimination while serving their country, returned home after fighting in conflicts including World War II and the Korean War and helped drive the civil-rights movement.

Today the Foreign Service—often described as “pale, male and Yale”—is by some measures even less diverse than it had been in prior decades. Of 189 current U.S. ambassadors, only three are Black. All are men.

“I’ve always felt there was a mental bias on the part of most white people in America, including in the Foreign Service, that one or two Black people is fine, but there’s some kind of limit over which the more Black people you have, it becomes unacceptable,” Brazeal told me.

“In Japan, for example, you are what your business card says you are, and so people treat you at that level,” Brazeal said of a posting in Tokyo in 1987. “It was the Americans you’d run into who could sometimes be weird. I remember one cocktail party, I was talking to this white man who told me: ‘You know, I’ve got to leave because there’s nobody who looks like me.’ And I said, ‘Funny you should mention that. That’s how I feel in the States.’”

[Read: The decline of the American world]

There is a cost for the pervasive scarcity in representation among those who are the face of America abroad: The Association of Black American Ambassadors this summer published an open letter calling for action to fight racism at home in order to maintain credibility advocating for human rights and justice beyond our borders. Yet there is an additional cost, incurred through the inability or unwillingness to understand or capitalize on the desire of nonwhite, non-male Americans to represent American interests.

“It’s public service and it’s pride in the nation and subscribing to the belief that we, too, must be part of who is out there speaking for America,” Abercrombie-Winstanley told me.

Abercrombie-Winstanley showed up on the first day of her Foreign Service orientation in 1985 one of 13 women and two Black people in a class of 52. Over drinks that first week, several of her new colleagues started a guessing game about how many members of the new class were affirmative-action hires. “It gave me a sense of what the FS would be like early on,” she said. The discrimination would not end there: Abercrombie-Winstanley arrived in Baghdad during the Iran-Iraq War for her first diplomatic posting to head the embassy’s consular section, the only woman head of a department at the time. A diplomat who picked her up at the airport told her that during an embassy staff meeting, someone announced Abercrombie-Winstanley’s appointment by saying: “Not only is she a woman, but she’s Black!”

Abercrombie-Winstanley went on to spend much of her career in the Middle East, moving from Iraq to Egypt, then later becoming the director for the Arabian Peninsula at the National Security Council, eventually being named the first woman to manage the U.S. consulate in Jeddah.

At the time, a female ambassador who had spent many years in the region warned her to “watch out for our own men, not the locals. The locals take you as you are.”

[Ta-Nehisi Coates: The case for reparations]

Pretty soon, Abercrombie-Winstanley said, she was treated as just one of “the Americans” by the royal family and most government officials—all men. But she also crossed many thresholds that no women, not even Westerners, crossed in the kingdom, thereby implicitly enacting America’s explicit foreign policy of promoting women’s rights. “I know I had an impact on Saudi women who spoke to me about what it meant to them to see the Americans sending a woman to head up the diplomatic mission and for a woman to be the U.S. president’s representative,” she said.

Page, who in 2011 became the first U.S. ambassador to newly independent South Sudan, told me how being Black and a woman—and the face of America before a fledgling country—held enormous significance. She recounted stories of women she met who left their homes to attend college and postgraduate programs in the U.S. before returning to South Sudan “to have a profound impact on their country.”

This has always been the central aim—and the grander dream—of American diplomacy: to introduce our idealized notion of a nation to the world. What hasn’t yet been recognized, reckoned with, or understood is that for some American diplomats, it remains an ideal only realized far from home.