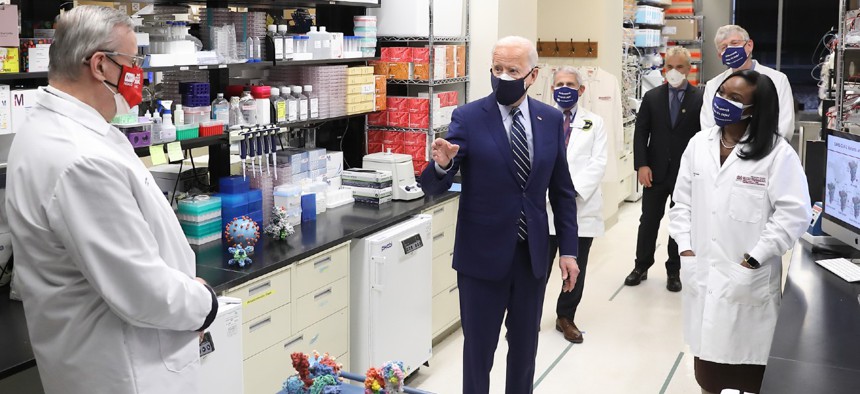

President Biden visits NIH to meet with leading researchers at the Vaccine Research Center to learn more about the groundbreaking fundamental research that enabled the development of the Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines. Chiachi Chang / NIH

NIH is Documenting COVID-19 as Well as Responding to It

"It’s weird to be documenting something that you’re living through," said an archivist.

In addition to its research and clinical efforts for the coronavirus pandemic, the National Institutes of Health is archiving material for historical and future research purposes.

Shortly after the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” on January 30, 2020, NIH’s National Library of Medicine launched a process to collect web and social media documents on the virus. This was before WHO declared it a pandemic on March 11, 2020.

“Our scope is broadly focused: [the National Library of Medicine] is interested in preserving content documenting the many social and cultural dimensions, efforts to control and prevent the spread, health disparities, the impact on vulnerable populations, vaccine development, health worker and patient experiences, misinformation, and more,” Christie Moffatt, chair of the library’s web collecting and archiving initiative, told Government Executive. “We also select content documenting the many stories of innovation, creativity, and hope in the face of this crisis.” The purpose is to save the material “for future research, and the future historical record.”

The National Library of Medicine is also working with the Smithsonian Museum of American History, the Food and Drug Administration History Office, the David J. Sencer Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Museum and Veterans Affairs Department as well as “engaging with many agencies using the Internet Archive’s Archive-It service to collect web content,” Moffatt said. The service, a nonprofit established in 1996, is a leading web archive for government, academic, cultural and other libraries.

The National Library of Medicine is also collecting research publications and data related to the pandemic through PubMed Central, its digital repository. In the past year the library, with help from its partners, has collected over 6,000 resources, which equals over one terabyte of data.

The Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum is also working on archiving initiatives. It developed its documentation plan with input from NIH’s Records Management Program, National Library of Medicine, and Office of Research Facilities.

“We’re documenting the background of major NIH initiatives as well as capturing a variety of voices: an IC director, nurses, physicians, bench scientists, grants officers, HR officers, facilities managers,” said Michele Lyons, associate director and curator of the Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum. “We’re talking to basic scientists before their research is published. It’s overwhelming, but probably the most important thing many of us will do in our careers.”

Some of the things the office and museum have collected so far are: over 1,716 citations and print and electronic articles about NIH, 335 NIH daily news briefings, over 50 interviews with NIH staff, over 700 staff COVID-related emails, hundreds of photos (including one of a llama named after Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases), artifacts such as nasal testing swabs, over 900 urls of NIH’s podcasts, and video and radio segments.

In addition to photos of work being done at NIH during the pandemic, they are collecting photos with NIH themes, such as the llama. The llama was born on April 26, 2020 in Indiana, which was early on in the pandemic, and was named “Providence Raphael Anthony (Tony),” to honor Fauci and Saint Raphael, the patron saint of nurses, doctors and medical workers.

“About a month in, the question changed from ‘how long will this go on?’ to ‘How will we document this?’” said NIH Archivist Gabrielle Barr. “It’s weird to be documenting something that you’re living through.”

The Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum learned from its efforts to document the agency’s role in the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, but “we have a lot more ways to document things now,” Lyons said.

Since the start of the pandemic, “most of the requests [for information from the archives] have focused on Dr. Anthony Fauci and his role in AIDS and Ebola, etc.,” she added. Fauci has been NIAID director since 1984 and been at NIH since 1968. “We anticipate many documentarians and historians using our collections to give a more complete look at the NIH’s involvement in the years to come,” said Lyons.

Government Executive recently spoke with NIH Director Dr. Francis Collins about the agency’s coronavirus vaccines, testing and therapeutics work, its study of long-term effects of the virus and more.