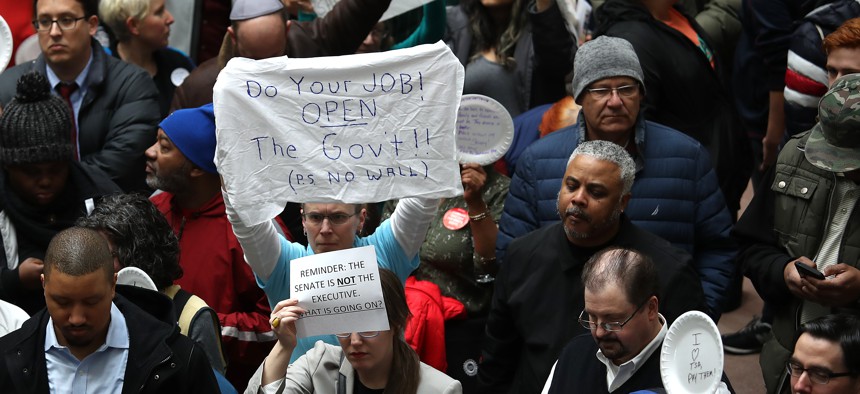

Win McNamee/Getty

That Time a Lawyer Invented the Government Shutdown

For nearly 200 years, shutdowns simply didn’t happen, even when Congress didn’t finish spending bills.

The latest in an intermittent series looking back at groundbreaking, newsmaking, appalling and amusing events in government history.

At the end of September, in what has become an annual event, Congress and the president agreed on a short-term funding measure to keep federal agencies from having to close their doors. The ritual often includes going to the brink of a government shutdown repeatedly, while the laborious playacting of negotiating an omnibus funding measure for agencies unfolds.

For nearly 200 years of the country’s history, this never happened. Everyone just assumed that if Congress didn’t get around to finishing appropriations bills, then agencies would just continue operating as normal until lawmakers got the job done.

Then one day in 1980, a presumably well-meaning attorney general, Benjamin Civiletti, invented the government shutdown. He didn’t intend to. Civiletti was just providing legal advice to President Carter on what should happen in the event of a lapse in appropriations at an agency.

“I couldn’t have ever imagined these shutdowns would last this long of a time and would be used as a political gambit,” Civiletti told the Washington Post in 2019. He said he was only offering “a purely direct opinion on a fairly narrow subject” that “has been used in ways that were not imagined at the time.”

“Our country survived the Civil War, the Great Depression, and World War II, all without anyone ever once shutting down the government,” lawyer and former Agriculture Department official Kenneth Ackerman wrote in 2019. “And no, it’s not that we never had accounting snafus in Washington before 1980. But up until that year, no president or attorney general ever took the crazy position that a gap between agency appropriation bills—the expiring of one coming a few hours or days before enactment of the next—amounted to a doomsday machine for politicians to hurl about Capitol Hill, causing the government to lock its doors.”

So how did Civiletti come to offer his opinion? The story starts in the 1970s, when funding lapses started to occur not just due to “accounting snafus,” but because appropriations measures became entangled with legislation on hot-button issues such as abortion and school integration. From fiscal 1977 to fiscal 1980, there were six gaps in federal funding, ranging from 8 to 17 days. Congress was making a practice of not finishing spending bills on time—a habit that would grow dramatically worse in the 21st century.

One lawmaker, Rep. Gladys Noon Spellman, D-Md., became curious as to whether periodic lapses in funding ran afoul of an obscure 1884 law called the Antideficiency Act.

Spellman asked then-Comptroller General Elmer Staats what he thought. In March 1980, Staats responded that while technically the law prevented agencies from spending money that hadn’t been appropriated by Congress, that didn’t mean lawmakers wanted operations to come to a screeching halt while funding decisions were being sorted out.

"We do not believe that the Congress intends that federal agencies be closed during periods of expired appropriations," Staats wrote.

Enter Civiletti. Six weeks after Staats’ letter, the attorney general weighed in. The comptroller general was wrong, Civiletti wrote in a letter to President Carter. “It is my opinion that, during periods of ‘lapsed appropriations,’ no funds may be expended except as necessary to bring about the orderly termination of an agency’s functions, and that the obligation or expenditure of funds for any purpose not otherwise authorized by law would be a violation of the Antideficiency Act.”

Then Civiletti went further. The Justice Department, he said, intended to enforce the criminal provisions of the act against federal officials who continued running their agencies without funding. That meant fines of up to $5,000 and as much as two years in prison.

It didn’t take long after Civiletti issued his opinion for the first shutdown to occur. It involved only the Federal Trade Commission, whose appropriations were allowed to lapse on May 1, 1980, while lawmakers wrangled over an authorization measure for the agency. The shutdown lasted only a day.

It quickly became apparent, though, that the broader implications of the Civiletti opinion were rather dire. What if the FBI or the Secret Service ran out of money? Would federal law enforcement agents be required to walk off the job?

So in 1981, Civiletti issued a second opinion: Even in the absence of appropriations, he wrote, some government functions could continue, as long as there was “some reasonable and articulable connection between the function to be performed and the safety of human life or the protection of property.” This would morph into the “essential vs. nonessential” employee mis-designation that now reappears every time a shutdown occurs.

Over the next 14 years after Civiletti established the basic ground rules for shutdowns, there were multiple brief closures of agencies. But none lasted more than a few days. That changed in fiscal 1996, when House Speaker Newt Gingrich, R-Ga., engineered a pair of shutdowns, one lasting 21 days. That turned into a political victory for President Clinton, and deterred shutdowns for more than a decade. But they reappeared in the early 2000s, and have been a fiscal fixture ever since.

That, in turn, has led to steady growth in the length of the list of federal operations whose work is deemed to be connected to the protection of life and property. And agencies have become more and more creative in finding non-appropriated sources of funding and hidden cash reserves to stay open in the event of shutdowns.

Meanwhile, federal employees are treated as pawns in the whole process, having to repeatedly endure furloughs. In 2019 Congress apparently felt guilty enough about this to guarantee that they would receive back pay at the end of shutdowns.

It didn’t have to be this way. If Civiletti had agreed with Staats’ interpretation of the Antideficiency Act, it’s possible that shutdowns would have remained relatively rare and short. But there’s no putting the genie back in the bottle. Now that shutdowns have been weaponized as a negotiating tactic, certain lawmakers would be only too happy if lapses in funding essentially led to indefinite continuing resolutions. A lack of formal appropriations would likely go on for months, or even years.

It’s hard to imagine a worse state of affairs than we have these days. But that would be it.