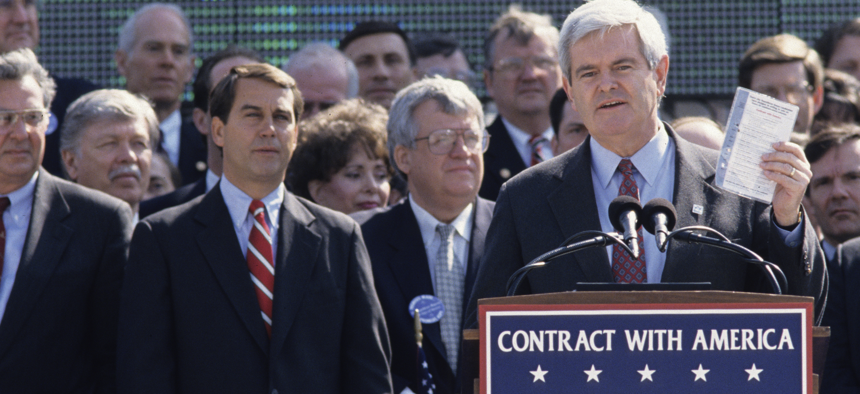

Newt Gingrich holds up a copy of the Contract With America at a ceremony marking the GOP's first 100 days in control of the House in 1995. Erik Freeland/Getty

What the Midterms Mean for Government

Setting a new course for the ship of state is harder than it looks.

In January 1995, a fresh-faced, 32-year-old newly minted congressman from Florida named Joe Scarborough arrived in Washington. He was part of the wave of Republicans who took control of the House of Representatives in the midterm elections for the first time in four decades. Just weeks after being sworn in, Scarborough was on the floor of the House leading a debate on “changing the direction of government.”

He and a group of other freshmen lawmakers dubbed themselves the New Federalists, and pledged to “privatize, localize, consolidate [or] eliminate” the departments of Commerce, Education, Energy, and Housing and Urban Development.

More than a quarter-century later, all of those departments still exist, and Scarborough long ago moved on from Congress to host MSNBC’s “Morning Joe.”

He and his fellow revolutionaries quickly learned that dismantling government wasn’t as easy as it looked, and maybe not as necessary. In March 1995, Scarborough and other GOP legislators hauled then-Education Secretary Richard Riley before the Government Reform and Oversight Subcommittee on Human Resources and Intergovernmental Affairs to justify the department’s existence given what Scarborough called the “new wave sweeping Washington.”

Riley, saying he wasn’t in his position to “save the job of a bureaucrat,” patiently explained that the Clinton administration had already proposed cutting Education’s budget by more than $16 billion over five years, eliminating 41 programs.

“What you all have done in the last two years appears to be very positive,” Scarborough conceded after Riley’s testimony. Maybe the department’s budget could simply be frozen for a couple of years, GOP members of the subcommittee said at the end of the hearing.

That tells you something about midterms, revolutions and the staying power of the federal bureaucracy.

A Hold on the House

Historically, midterm elections haven’t had much impact on reducing the size of government or changing the way it is managed. There are three reasons for this. First, for decades, Democrats had an iron grip on the House and never had to cede complete control of Congress. Second, it’s harder to eliminate or overhaul a department than to create one. And third, federal management has historically been a bipartisan issue.

From 1955 to 1995, Democrats held a majority in the House, despite changes in control of the Senate and occasional landslide victories by Republican presidential candidates. That meant that not only could they wield substantial power of the purse, but could set the legislative agenda in half of Congress. And they were in the business of building government’s capacity to do everything from ensuring a social safety net to landing on the moon. So were many Republicans.

That changed with the midterm elections of 1994. That year, Republicans offered a specific, detailed “Contract With America” outlining their governing agenda. “This year’s election offers the chance, after four decades of one-party control, to bring to the House a new majority that will transform the way Congress works,” the Contract read. “That historic change would be the end of government that is too big, too intrusive and too easy with the public’s money.”

Assessments vary about how much of an impact the Contract With America had on the outcome of the election, but the Republicans swept to victory. Then they set to implementing their specific detailed plan. It promised votes on legislation to require a balanced budget, provide the president with line-item veto authority and mandate zero-based annual budgeting.

More broadly, the Republicans, especially freshman lawmakers like Scarborough, sought to eliminate entire agencies, slash government employment and scale back federal pay raises and retirement benefits.

Easier Said Than Done

The new Republican leadership certainly succeeded in changing the terms of debate over the size and role of government. Within two years, Democratic President Bill Clinton would famously declare that “the era of big government is over.”

When it came to specific achievements, however, the terms of the Contract proved difficult to implement. Newly minted House Speaker Newt Gingrich promised sweeping legislative achievements in the GOP’s first 100 days in control of the House, and lawmakers did approve a balanced budget amendment, a freeze on federal regulations and other measures. But these pieces of legislation all fell short in the Senate.

“This is not a monolithic Roman legion marching inexorably toward victory,” Gingrich acknowledged at the hundred-day mark.

Nevertheless, the Contract With America set a precedent. Republicans—and some Democrats—have over the years continued to offer contract-like pledges to the American people. As this year’s election cycle heated up, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, released a GOP “Commitment to America.” It promised, among other initiatives, “a government that’s accountable”—including a threat to use subpoena power to back up more than 500 requests for information about federal activities that GOP lawmakers have already sent to the Biden administration.

The Commitment to America, however, attracted little attention, and is unlikely to have much impact on the outcome of the midterm elections. But if the Republicans retake the House, it could bog down committees tasked with developing legislation governing how federal agencies are managed. Instead, their focus would likely be on politically charged partisan investigations.

Bipartisan Approach

Almost all of the major initiatives to fundamentally change the management of government have passed with bipartisan support. This was, ironically, especially true in the 1990s, in the period surrounding the Republican “revolution” of 1994.

On the Senate side, Democrat John Glenn of Ohio and Republican William Roth of Delaware traded off the chairmanship of the Governmental Affairs Committee, but cooperated on management-related legislation. These included the 1990 Chief Financial Officers Act, the 1993 Government Performance and Results Act, the 1994 Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act, and the 1996 Federal Financial Management Improvement Act.

Likewise, leaders on the House side treated these and other management-related legislation in a generally bipartisan fashion. That tradition held even as Congress became more polarized. Reps. Gerry Connolly, D-Va., and Darrell Issa, R-Calif., who no one would accuse of being shrinking violets when it comes to fighting for their party’s agenda, cooperated on key pieces of legislation, including the landmark 2014 Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act. Earlier this year, they launched the Congressional IT Modernization Caucus.

Management-related bills still tend to attract more bipartisan support than tax, spending and appropriations measures, which recently have required nail-bitingly close partisan votes to pass. Witness this year’s Postal Reform Act, which passed with broad bipartisan support in both chambers of Congress.

Amidst polarization, there’s even hope for the contentious world of government oversight. “Even amid House Democrats’ often contentious oversight of the Trump administration in 2019 and 2020, occasional bipartisan investigations emerged—and an early look at the 117th Congress to date suggests oversight can still be bipartisan even during high partisan conflict,” the Brookings Institution reported last year.

This doesn’t necessarily mean, unfortunately, that management and oversight issues are being handled with a high rate of efficiency and effectiveness. The Lugar Center, founded by former Sen. Richard Lugar, R-Ind., and dedicated to, among other priorities, “enhancing bipartisan governance,” publishes an ongoing “Congressional Oversight Hearing Index.” For this session of Congress, the House Oversight and Reform Committee gets a grade of F.