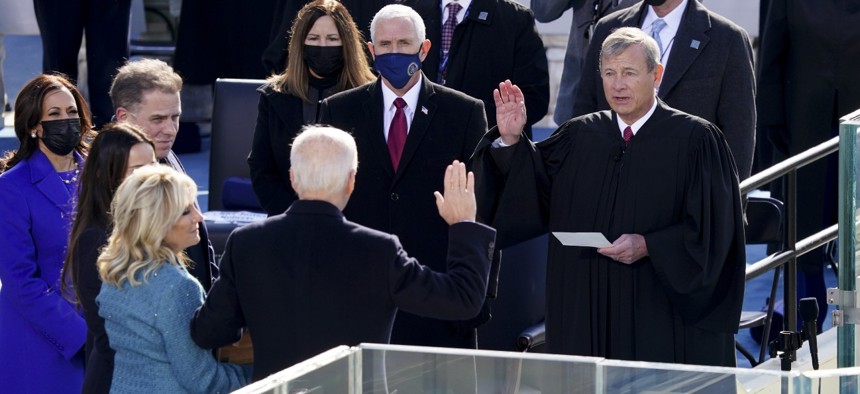

John Roberts, chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, center right, administers the oath of office to President-elect Joe Biden on Jan. 20, 2021. Kevin Dietsch-Pool/Getty Images file photo

The Presidential Transition Law is Getting an Update

“Transitions are not just about measuring the drapes,” said one expert.

After Election Day 2020 but before the attack on the U.S. Capitol, a somewhat unknown and arcane process was thrust into the national spotlight as then-President Trump’s campaign mounted legal challenges to the election results and he refused to concede.

This process was the head of the General Services Administration's “ascertainment” of an election winner to allow the presidential transition to begin. Although GSA did eventually ascertain Biden as the winner, and the Biden team ultimately had what some observers have said was a highly successful transition operation by historical standards, there was a long delay while the GSA chief figured out how to handle the situation.

“Unfortunately, the [transition] statute provides no procedures or standards for this [ascertainment] process, so I looked to precedent from prior elections involving legal challenges and incomplete counts,” wrote then-GSA Administrator Emily Murphy when she ascertained Biden as the winner on November 23, 2020, more than two weeks after all major news outlets declared him the president-elect. “I do not think that an agency charged with improving federal procurement and property management should place itself above the constitutionally based election process. I strongly urge Congress to consider amendments to the act.” She also outlined the challenges she faced while under enormous pressure to ascertain Biden as the winner, so his team could start its full preparations to take over.

The delay in ascertainment and uncertainty over what should happen when a candidate refuses to concede is something lawmakers are looking to avoid in the future by adding a provision updating transition law to the fiscal 2023 omnibus spending act. The language, first introduced over the summer by a bipartisan group of lawmakers as the separate “Presidential Transition Improvement Act,” seeks to ensure that future administrations are ready to govern on Day 1.

The Updated Transition Law

The newly enacted statute will allow for more than one presidential candidate to receive transition resources if there is a time period when the result of the election is “reasonably in doubt.” It then spells out what the GSA administrator should consider to decide the certainty of the election outcome: whether or not legal challenges that could change the result are resolved; states’ certification of their election results; and “the totality of the circumstances.”

A candidate will be the only candidate eligible to receive transition resources when they receive the majority of pledged election votes and there aren’t any other legal or administrative actions pending; they receive the majority of the electoral votes at the electors meeting in December after the election; or they are formally elected during the joint congressional meeting on January 6.

If neither candidate has conceded, then the GSA administrator has to report on the federal resources given to both candidates; provide Congress with weekly updates on the transition; and issue a written public opinion on the legal basis and reasons for a single candidate being ascertained the winner of the election.

Besides the ascertainment matter, the 2020 to 2021 transition took place in a mostly virtual environment due to the COVID-19 pandemic and culminated with the attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, as lawmakers were taking up certification of the election results.

Reaction to the New Reforms

Troy Cribb, director of policy at the Partnership for Public Service, a nonprofit that is highly involved in the transition process, said it’s a “tremendous success” that the ascertainment reforms were included in the omnibus because this will really fill in a gap in the situation where the election results aren't clear for some time.

“If you look at the arch of improvements to the presidential transition act over the last couple of decades, the changes that Congress has made really reflect and have helped drive the notion that transitions are not just about measuring the drapes,” Cribb said. “It’s a serious activity that any presidential candidate needs to prepare for in order to assume the office of the presidency. So, these changes that Congress is including in the omnibus really continue that trend.”

She added that all of the reforms to the transition law over the last decade have been on a bipartisan basis, which is an “incredibly important recognition that everybody needs to have faith that the process will be fair no matter what the political affiliation is of the president elect.”

The reforms also earned high marks from the Protect Democracy, a nonprofit dedicated to strengthening democratic institutions. Retiring Sen. Rob Portman, ranking member of the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, called them “noncontroversial reforms,” which are “extremely important to prevent bad-faith actors from exploiting ambiguity in the law for political motives.”

Heath Brown, associate professor of public policy at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York and CUNY Graduate Center, who studies and writes on presidential transitions, told Government Executive the reforms are “called for” and “timely.”

We don’t know when the next transition will be, “but 2020 clearly exposed some gaps in the system that exist,” he said. “Whether this current kind of fix does very much is not clear to me right now. There seems to be some additional holes there; things that are left unclear, but it's certainly timely.”

Brown said that he learned through research for his upcoming book on the 2020 transition that the changeover “is all centered-on cooperation” and sharing of information by the political and career officials, especially the classified briefings.

“It’s not clear what the bill does to make sure that future transitions give access to those people in a timely fashion and that those people will be openly sharing the information about the activities of the federal government,” which aren't known publicly, Brown said. Those were “the parts of the 2020-2021 transition that sputtered. [They were] typically around political appointees in the Trump administration who were less than open to cooperating with the incoming Biden administration. It’s not clear how the bill would address that in the future.”

The national security aspect of transitions came to the forefront in wake of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks and the 9/11 Commission made recommendations on how to improve the transition process after examining what happened in the 2000-2001 transition, which was shortened due to the Supreme Court case over the election results.

After the ascertainment, in December 2020, the executive director of Biden’s transition said that while many agencies and departments were working to share information with them, there were some “pockets of recalcitrance,” including the Defense Department. In April 2021, then-White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki blamed the Trump administration’s lack of cooperation during the transition in part for the delay in releasing the Biden administration’s budget preview.

Jim Williams, who served as acting GSA administrator during the George W. Bush to Obama transition in 2008-2009, said he wasn’t sure if any of these reforms were necessary. “I liked, when I was acting administrator and made the ascertainment decision for selecting the apparent successful candidate Obama, that I had wide latitude,” he said. Meanwhile, this legislation appears to put things into a “narrower box” and is in response to what was probably a one-off situation in 2020-2021.

Williams said he does think it's good to let the transition go forth with two candidates if the winner is not clear, so the incoming administration has as much time as possible to get ready to govern. He also said that even after the ascertainment decision was made in 2020, from what he heard, there was a hindrance of transition discussions, so it should be clear in the law that that can’t happen.

Now that the midterm cycle is over, all eyes are on 2024, which could be the start of the next transition. If not, 2028 will be the first time the new law is put to the test.