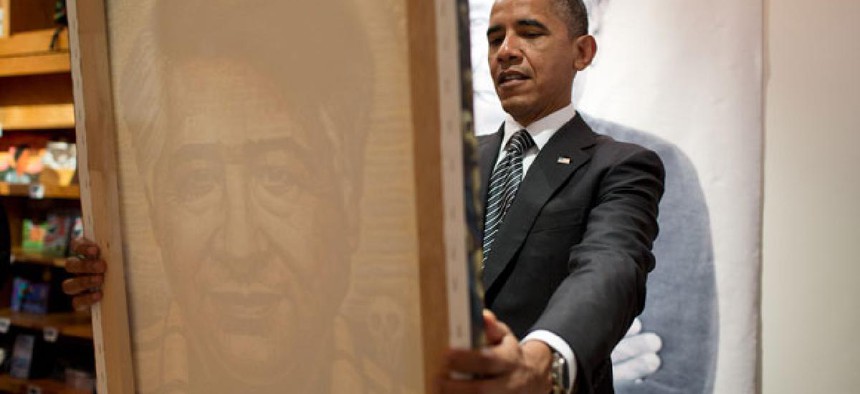

White House photo

Huge Hispanic Support for Obama Was No Sure Thing

The president's reelection campaign had to ratchet up its efforts to woo the Latino vote.

At this point, the narrative is pretty familiar to all: President Obama beat GOP nominee Mitt Romney by 44 percentage points among Latinos, 71 percent to 27 percent, exceeding the 67 percent of the Latino vote he won in 2008 over John McCain. Obama’s popularity among Hispanics since Election Day remains impressive; Gallup’s compilation of about 15,000 total interviews each month shows the president with job-approval ratings among Latinos of 74 percent in November, 75 percent in December, and 70 percent in January.

But as recently as a year ago, one might not have guessed this would happen. In January 2012, Obama’s approval rating among Latinos stood at only 55 percent, 12 points below his share of the 2008 Latino vote. During 2011, his rating among this group dropped as low as 48 percent, with a 41 percent disapproval rating. In other words, Obama’s big electoral win among Latino voters, who made up 14 percent of his total vote according to national exit polls, was not a foregone conclusion.

For much of the president’s first term, grumbling among Latino voters was considerable. The jobless rate was significantly higher among Hispanics than the population as a whole; indeed, the Latino unemployment rate was at 12 percent or higher for 20 of 24 months during Obama’s first two years in office; it was in double digits for 45 of the entire 48 months. Not that many blamed Obama for a recession that began before his election, but who could fault Hispanics for feeling disaffected or less-than-energized about his reelection?

And although Hispanics took offense at much of the rhetoric emanating from many conservatives and certain Republicans at the time, the deportation rate of undocumented workers was running at a higher rate in the first three years of Obama’s presidency than it had during George W. Bush’s administration. Given the key role that Latinos had played in Obama’s 2008 win, this particular leg of his coalition looked pretty wobbly just a year and a half before Election Day.

Little wonder that when pollsters, including Gallup, Peter Hart and Bill McInturff for NBC News and The Wall Street Journal, and others, asked Latino voters eight or nine months ago how enthusiastic they were about voting or how likely they were to vote, the response was like the sound of one hand clapping. It looked as if Obama might not only get a lower percentage of the Latino vote—that is, winning it but by an unimpressive margin—but that turnout among this key group might be lower as well.

So what happened? The president’s trial-heat matchups against Romney and other potential Republican challengers were always better than Obama’s often underwhelming approval ratings. Romney only exacerbated this lack of enthusiasm for the GOP by suggesting that some Hispanics might consider “self-deportation” and by making other clumsy moves as he sought to outflank Texas Gov. Rick Perry on the right during their party’s presidential primaries. So to a certain extent, Romney’s troubles were self-inflicted.

But it is also the case that when the Obama campaign decided to ratchet up its efforts to woo the Latino vote, buttressed by Hispanic-friendly policy pronouncements coming out of the White House, it was enormously effective. When the Romney campaign ran a Spanish-language ad in key states targeting Latino voters, it often was simply a translation of an ad aimed at non-Latino voters. By contrast, the Obama campaign featured prominent leaders in a local Latino community speaking Spanish in ads aimed at that specific audience. Throughout the campaign, the Obama operation did a much better job than the Romney campaign of synchronizing messages with target groups.

This effective targeting of key constituencies carried over into the fieldwork of identifying supporters and getting them out in big numbers on Election Day or, better yet, before then in early-voting states. Even in polling by various news organizations going all the way up to Election Day, certain groups looked less likely to turn out in vigorous numbers than they eventually did—notably, Latino and younger voters. This suggests that the outcome was not a case of spontaneous combustion. It was not organic; it was organized and orchestrated by a campaign operation that had been finely tuned over four years to do this.

As we sift through the polling data and the various postmortems, and as participants become more willing to discuss what was going on behind the scenes, it becomes very clear that this election had its own course that was not obvious to outsiders, and that is why things went a different way than one might have guessed a year or so ago.