Adam Gregor/Shutterstock.com

Analysis: Want Effective Government? Then You Have to Pay Better

Civil servants face a brain drain if Congress persists with pay freezes, benefit cuts, and badmouthing dedicated employees.

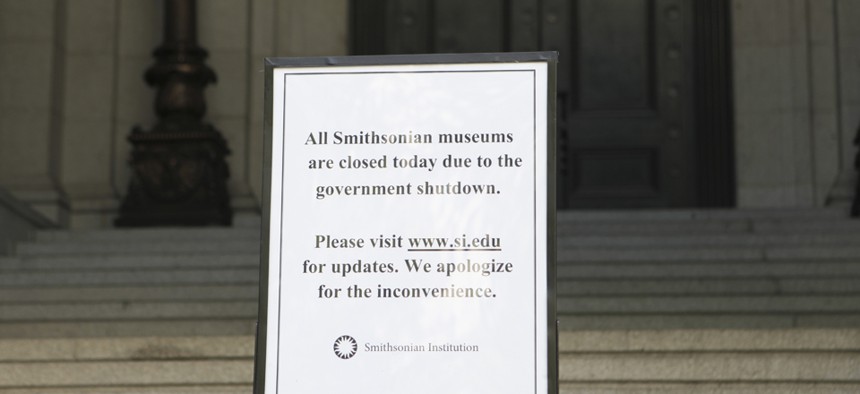

The ill-fated shutdown of the federal government last year had one modestly positive side effect: It reminded many Americans about the important things government does. To choose just a couple of examples, the closure of national parks not only blocked access to national treasures from visitors, but it also caused deep damage to a wide range of local and state economies, because the businesses that depend on the parks—hotels, restaurants, outfitters, guides, souvenir shops, and so on—were devastated. The shutdown of the National Institutes of Health reminded many Americans about the key role federally driven and sponsored medical research plays in our health and well-being and in our economic and scientific prominence.

The shutdown moved at least some of the discussion and perception away from the deep hostility Americans have for bureaucrats and bureaucracy, and the antipathy huge majorities in the country feel toward Washington, and made the stories personal and the image concrete. Park rangers, research scientists, Border Patrol agents, first responders, disaster-relief personnel, FBI agents, firefighters, air-traffic controllers, Foreign Service officers, and many more people who make Americans’ lives safer and easier, and protect our well-being and security, are all, in the parlance, “bureaucrats.” But their jobs are vital, and the overwhelming majority of federal employees are conscientious people who take their jobs seriously and work very hard at them.

For decades, most members of Congress—liberals and conservatives alike—understood that reality. Conservatives, to be sure, had a deeper skepticism about government as a problem solver and believed in a smaller government. But they also believed that the government we should have—including protecting against enemies at home and abroad, securing the borders, conducting basic research, building and operating highways and other forms of interstate transportation and commerce, running national parks—should be run well and efficiently, by competent and qualified people.

The kinds of sound management principles that business uses resonated with business-oriented conservatives.

Of course, there were spasms of partisan paranoia over the underlying political leanings of career employees, and partisan tugs of war over how much control administrations would have over career people, and occasional scandals over excessive political influence or pressure. But bipartisan efforts to streamline government service, protect at least modest pay increases, and reform management procedures were the norm, not the exception, including the landmark civil-service reform enacted during the Carter Administration that created the Senior Executive Service to encourage top career-professional managers at the senior levels, and to create a pay and benefit structure that could attract top people.

Of late, the old coalitions have disappeared, and new schisms have developed. One of the most significant is the sharp rise of radical, antigovernment sentiment on the right. This is not “leaner and meaner” government conservatism, but a more visceral attitude of hostility to all government—government as an overweening evil. It is an attitude that rejoiced in the shutdown, that shut out any evidence that closing any part of government could actually hurt people or damage the economy. And it is deep-seated enough among activists that harsher antigovernment rhetoric, and policies designed to make the lives of government employees more difficult, have emerged in full force. Pay freezes, cuts in benefits, attempts to take away any small perks or rewards, fueled in many cases by hyped outrage over real and exaggerated scandals, have taken their toll. It also fuels a push toward more privatization, even where such a move is more costly and more prone to corruption.

But this approach is not the only challenge facing governance in the 21st century; the structure of the career civil-service system is not up to the tasks facing the country in a global economy and in a technology-driven age, with its attendant challenges at home and abroad. The excellent core of professional managers created by the 1978 reforms is nearing a major gap: By 2017, nearly two-thirds of the Senior Executive Service will be eligible for retirement, and it is not clear that another generation of talented managers is waiting in the wings to replace them.

More broadly, the recruitment process for federal professionals and managers is out of sync with the broader labor market, making it difficult to provide the incentives to recruit from among the best and brightest. As I wrote in an earlier column, how can a government fighting the danger of cyberwarfare and cyberterrorism compete with Intel, Google, Facebook, and Microsoft for topflight electrical engineers and computer scientists when it offers pay freezes and stripped-down benefits packages?

What to do? A penetrating new report by the Partnership for Public Service offers a passel of ideas as it calls for sweeping reforms. They include building a more market-sensitive labor system; merging many disparate personnel systems into one to level the playing field across government in the competition for talent; creating more flexibility for agencies to hire the best qualified people; creating pay-raise-for-performance incentives (and no raises for slackers) to improve performance management; creating a four-tier senior executive service to train managers better for the complex jobs they will have; and reducing the number of political-appointment positions to enable talented career managers to have more opportunities to advance.

The report makes a compelling case, one that actually reinforces many previous efforts at reform, for commonsense changes in an antiquated and unwieldy system. They have no partisan or ideological coloration—just sound management principles. It has been more than 35 years since the last major reform of the system. I wish I could be even modestly optimistic that the report will generate enough interest to get hearings and the start of a deliberative process, one that in the past might have been encouraged by respected lawmakers like Tom Davis and Frank Wolf. But with Davis retired and Wolf about to join him, and with the harsh antigovernment attitude ascendant, I can’t.

(Image via Adam Gregor / Shutterstock.com)