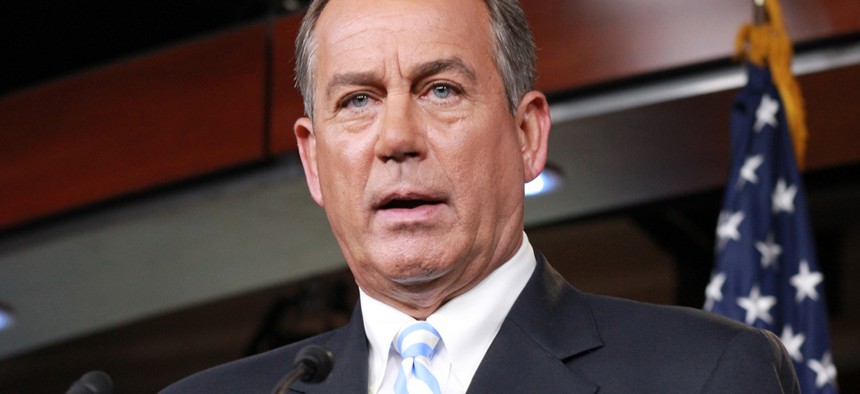

Flickr user talkradionews

The Boehner Lawsuit Against Obama Is Beginning to Take Shape

A vote on the resolution to authorize the legal action is set for the week before August break.

Starting next week, House Republicans will launch a highly visible—and likely tumultuous—three-week process of bringing to the floor legislation to authorize their promised lawsuit against President Obama over his use of executive actions.

"In theory, you could report out a resolution tomorrow and vote on it," said a House GOP aide on Tuesday. "But that is not the approach [the leaders] want to take."

Rather, the aim is to display—if not actually engage in—a more deliberative process, even if amid controversy. This drawn-out script builds toward a potentially dramatic floor vote held just days, or even hours, before the House adjourns on July 31 for its August-long summer break.

It will all start playing out when a panel of experts is called to testify next week on issues surrounding such litigation and to answer members' questions during a hearing of the House Rules Committee.

The resolution to authorize the legal action will then be formally written, or marked up, by the committee during a hearing the following week. The floor vote on the legislation will follow the week after that, in the days before the break.

Then, a bipartisan House leadership committee controlled by Republicans—the Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group, or BLAG—will finalize the language and legal direction of the lawsuit, deciding which arguments will have the most chances of success in a court.

Against this buildup toward actually filing the lawsuit, there is some Republican concern over the potential embarrassment of a quick dismissal of such litigation in the courts. In fact, legal experts say there looms a substantial roadblock in the form of a presumption against congressional standing required to maintain such a case in federal court.

Speaker John Boehner has so far provided few public details of what exactly will be in the lawsuit, or how that obstacle of its legal merits might be dealt with.

In an op-ed he wrote appearing this weekend on CNN's website, Boehner asserted that "the president has not faithfully executed the laws when it comes to a range of issues, including his health care law, energy regulations, foreign policy, and education." Boehner did not mention Immigration issues specifically.

But Boehner added, "The president has circumvented the American people and their elected representatives through executive action, changing and creating his own laws, and excusing himself from enforcing statutes he is sworn to uphold—at times even boasting about his willingness to do it, as if daring the American people to stop him."

But while Boehner was vague on legal specifics, two lawyers whom Republicans consulted on the issue have written a column entitled, "Can Obama's Legal End-Run Around Congress Be Stopped," in which they address some of the issues and arguments for such legal action.

David Rivkin Jr. and Elizabeth Price Foley write that Obama has worked around Congress with "breathtaking audacity."

Not only do they say he has unilaterally amended the Affordable Care Act multiple times—including delaying the employer mandate—they also write that the president has suspended immigration law, refusing to deport some young undocumented aliens.

And "with the stroke of a magisterial pen," they write, Obama has "gutted huge swaths of federal law that enjoy bipartisan support, including the Clinton-era welfare-reform work requirement, the Bush-era No Child Left Behind law, and the classification of marijuana as an illegal controlled substance."

The two lawyers note in their column that Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wis., has already filed a lawsuit challenging the president's decision to exempt Congress from the health-law exchanges. And they point out that Rep. Tom Rice, R-S.C., has a resolution, called the Stop This Overreaching Presidency that would authorize the House to legally challenge several presidential workarounds.

"But Congress's ability to reclaim its powers through litigation faces a substantial roadblock in the form of a presumption against congressional 'standing,' " Rivkin and Foley write. A plaintiff has standing in a case when he or she can demonstrate a concrete, particularized injury the court can remedy.

But the Supreme Court previously seemed to shut the door to congressional standing in a 1997 case, Raines v. Byrd, in which six members of Congress challenged the constitutionality of a presidential veto. The Court held that the claimed loss of congressional power by the six lawmakers was "wholly abstract."

At the same time, the two lawyers contend that the issue of standing should not bar enforcement of the separations of powers where "there are no other plaintiffs capable of enforcing this critical constitutional principle."

"This is because they are 'benevolent' suspensions, in which the president exempts certain classes of people from the operation of law. No one person was sufficiently harmed to create standing to sue, for instance, when Obama instructed the Department of Homeland Security to stop deporting young illegal immigrants," they write.

In addition, they write that in Raines, it was an ad hoc group of members of Congress that filed the suit. But, in a reference to BLAG, the lawyers argue that when House or Senate rules "have a mechanism for designating a bipartisan, official body with authority to file lawsuits on their chamber's behalf, the case for standing is more compelling."

"Then, the lawsuit is not an isolated political dispute, but a representation by one of the two chambers of the legislative branch that the institution believes its rights have been violated," they assert. "These types of serious, broad-based institutional lawsuits should be in a different category" than the Raines case, they assert.

"If congressional standing is denied in such cases, there will be no other way to check such presidential usurpation short of impeachment," the two write.

Obama has responded to the threat of the potential lawsuit by calling it a "stunt."

The president also said late last month, "If Congress were to do its job and pass the legislation I've directed them to pass, I wouldn't be forced to take matters into my own hands."