Supannee Hickman/Shutterstock.com

Debunking the Myth That Only Drivers Pay for Roads

Landing on the moon was still a wild dream the last time gas taxes paid nearly the full cost of our roads.

It's perfectly reasonable for American drivers to believe they pay for the roads they use. They’re aware that they pay gas taxes, but those costs are typically concealed in the total price of fuel, and there's no sign at the pump explaining that U.S. gas taxes are laughably low compared to other countries and haven't been raised in more than 20 years. Sure enough, when you ask people how much they pay in gas taxes, most either don’t know or think they pay much more than they really do.

The problem with this illusion emerges whenever it comes time to raise another round of highway revenue—as is the case right now in Washington. Voters and their political proxies balk at the idea of raising the gas tax. Some will invariably grab at the small share of this money that goes to public transportation; this year it's Reps. Thomas Massie and Mark Sanford who (separately) introduced legislation eliminating the mass transit account of the highway trust fund.

Here's Massie via press release:

"By eliminating diversion of gas tax revenues, the DRIVE Act ensures that the Highway Trust Fund can fulfill its namesake duty — to fund highways, without an increase in the gas tax rate."

That these bills won't pass isn't the point. They reflect a failure to appreciate that the gas tax is busted beyond repair, and with it the entire system of paying for road construction and maintenance. There are lots of reasons lawmakers are struggling to craft a long-term transportation funding bill at the moment, even as a May 31 deadline approaches, but the mistaken idea that drivers already pay enough for roads is among the biggest barriers to lasting progress.

So it's perfect timing for a new report debunking the myth that drivers alone pay for the full cost of roads. The trio of Tony Dutzik and Gideon Weissman of the Frontier Group and Phineas Baxandall of U.S. PIRG offer a thorough case that this "user pay" concept "has never been true, and it is less true now than at any other point in modern times." Their point is America can't begin to address its infrastructure crisis without correcting the "fundamental misunderstanding" at its core:

Roads don’t pay for themselves. We, the American people—whether we drive a lot, a little, or not at all—increasingly pay for them through other taxes and uncompensated costs.

We all pay for roads, and have for years

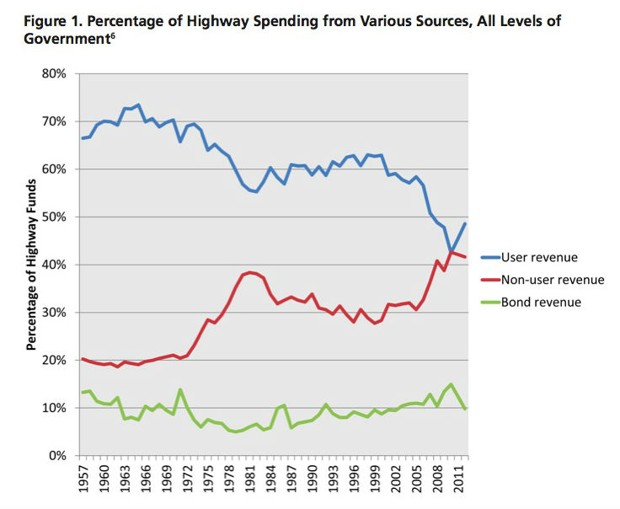

Landing on the moon was still a wild dream the last time gas taxes and other car-related fees paid nearly the full cost of building and maintaining roads. By the 1970s, road taxes still accounted for about 70 percent of road costs, according to Dutzik, Weissman, and Baxandall, but that link weakened in the '80s and '90s. Any vestige of a strong user fee died in the 2000s on account of peak driving rates, better fuel efficiency, soaring construction costs, and a gas tax held flat in the face of inflation.

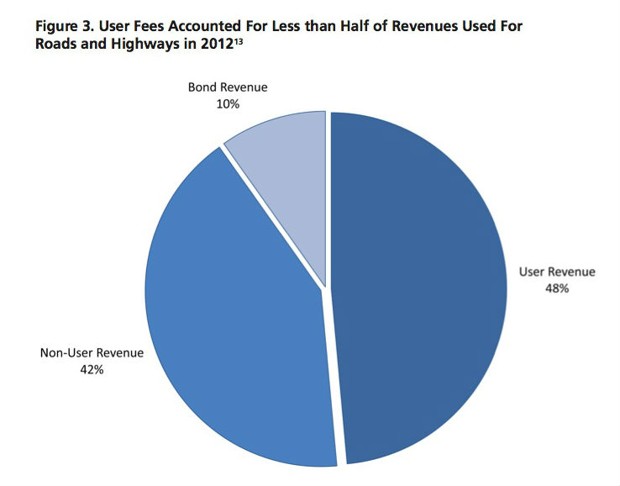

In recent years, tens of billions of dollars in general taxpayer money has been used (barely legally) to keep the Highway Trust Fund afloat. The theme weaves through all tiers of government. Using 2012 as an example, the report breaks it down like this: general taxpayers paid $47 billion in highway funding at the local level, $15.6 billion at the state level, and $6 billion at the national level—a total of nearly $69 billion, or almost $600 per household. Whether they drove or not.

That's not counting hidden subsidies and social costs

The use of general taxpayer money to construct and repair roads is enough on its own to shatter the concept that drivers pay their own way. But there's lots more to the problem—starting with the enormous social costs of driving. Those are the costs that society as a whole pays for car-reliance: the environmental impact of pollution, the health impact of accidents, and the economic impact of productivity lost to traffic, among them. These have beenestimated at $3.3 trillion a year.

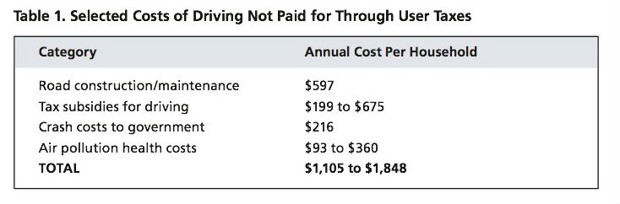

Then there are the hidden tax subsidies, to which Dutzik, Weissman, and Baxandall offer the following helpful hypothetical: let's say one person buys an $80 pair of shoes and another buys $80 worth of gas. You might think both would pay the same sales tax, with that money going toward certain local programs, while the driver would pay an additional gas tax, with that money going toward roads. In 37 states you'd be wrong—that's how many places have a fuel exemption for sales tax.

So poor shoe guy ends up paying for the programs that rely on the sales tax and paying for roads that inevitably take from general taxpayer funding (as mentioned above). Meanwhile the driver pays for roads alone—and insufficiently.

When you tally all these hidden costs together, alongside the assists that already occur for road construction and maintenance, the average household pays between $1,105 and $1,848 a year in what the report calls "uncompensated damage costs to support motor vehicle use in the United States." Again: whether they drive a lot or hardly at all.

We're an increasingly multimodal country

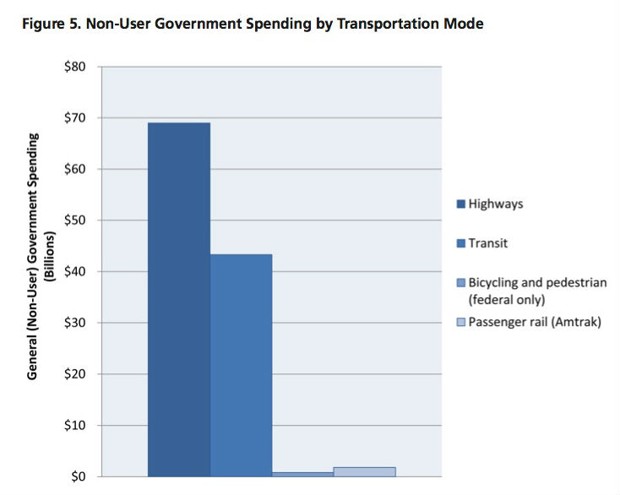

The point is not that drivers are ruining everything. At least, it should be, and to their credit, that's not how Dutzik, Weissman, and Baxandall frame their conclusion. Some drivers also suffer from these haphazard funding schemes: people who spend most of their time on neighborhood streets, for instance, pay a federal and state gas tax on top of the local source of road revenue (typically property taxes). And no one is suggesting transit users pay the full cost of trains or buses, either. Far from it.

Rather, the point is that America is an increasingly (and, now, majority) multimodal place, with a transportation network that offers personal options and collective benefits.The suburban drive-thru is harder to staff without a local bus. The city food joint is tougher to sustain without commuter lunch breaks. The two-day delivery is harder to make without interstates that stretch far outside the metro lines.

The reports suggests it’s time to pay for transportation as a system instead of as silos. That means allocating funding by need from a big pool, rather than setting it aside for a certain mode ahead of time. This approach works well for other advanced countries, which pay for transportation through their general budgets. In Europe, road taxes generate so much revenue they end up financing lots of other public programs.

It's also high time to enact a per-mile fee that can be adjusted for the types of transportation costs we'd like to capture—emissions, congestion, construction, maintenance, transit equity, and so on. There’s nothing for a dose of reality like an itemized monthly bill.

(Image via Supannee Hickman/Shutterstock.com)