Flickr user Gage Skidmore

How Trump Rose to the Top of the GOP Race

The billionaire consistently beat out his Republican opponents in the U.S. presidential race among the voters who matter.

Donald Trump has emerged as the presumptive Republican U.S. presidential nominee by assembling a coalition that proved remarkably consistent across geographic lines—and ultimately showed more breadth than any of his rivals.

From the primary campaign’s beginning to its effective end Tuesday night, Trump’s core strength remained his overwhelming advantage among several big groups in the GOP electorate, particularly whites without a college education and men.

But Trump also displayed more ability to reach across the party than any of his rivals, particularly in the weeks after his early April defeat in Wisconsin. In one telling contrast, Trump consistently fared much better among evangelical Christians—who Ted Cruz considered the foundation of his coalition—than Cruz did among voters who are not evangelicals. Over the past month, Trump has posted his best performances not only among the groups that preferred him from the outset, but many of those that had resisted him, including college graduates and women.

Despite a striking series of early victories that transcended the party’s usual geographic divides, Trump struggled through most of the primary season to consolidate majority support from his party. Until the New York primary on April 19, Trump did not capture 50 percent of the vote in any state. Trump then crossed that threshold in New York, as well as the five states in the Northeastern primaries last week and Indiana on Tuesday night. Those numbers suggested a pattern of crumbling resistance to Trump that encouraged Kasich and Cruz to quit the race. But even after those performances, Trump’s share of the total GOP vote cast in all the primaries and caucuses stood at about 40 percent.

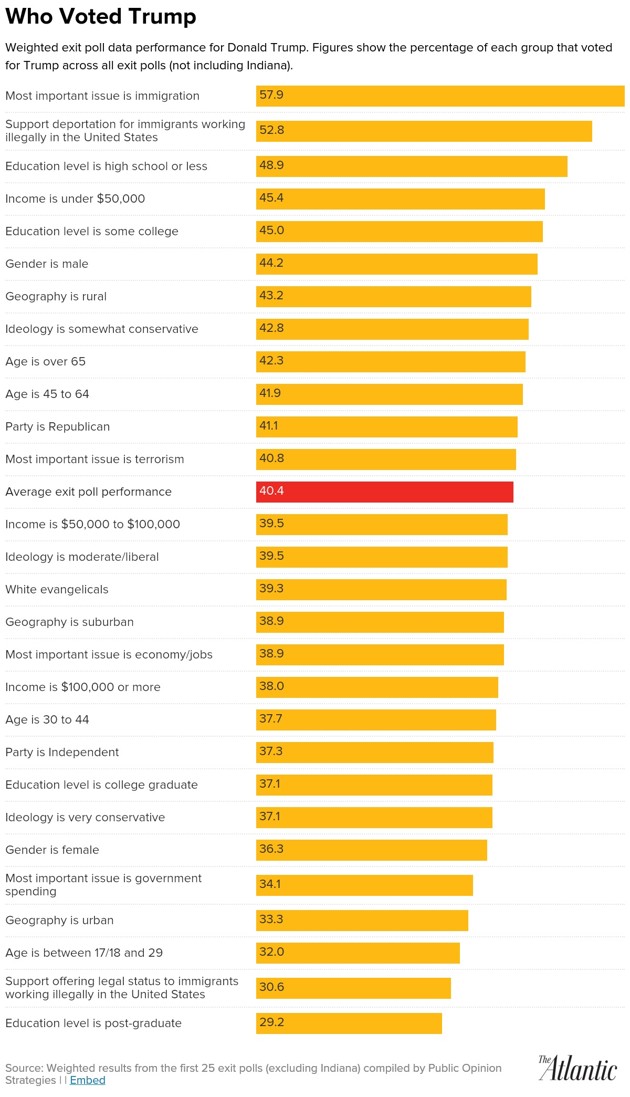

As the chart below clearly shows, there remains a clear hierarchy of support and resistance to Trump in the GOP coalition. The chart reflects analysis by the Republican polling firm Public Opinion Strategies, which estimated how Republicans voted by comparing exit polls to the number of votes cast in each state. The chart includes data for the first 25 states in which exit polls were conducted; it does not include the results in Indiana, where Trump posted extremely strong numbers among the groups usually drawn to him, and continued his post-New York pattern of improving numbers among those who were previously resistant to his candidacy.

Last October, I wrote that Trump’s strength in the race could be explained in two sentences: The blue-collar wing of the party had consolidated around him and the white-collar wing remained fragmented. That has remained largely true throughout this contest. Trump turned in dominant numbers among voters with only a high-school education, winning 49 percent of them, and those with some college, of whom he won 45 percent. He was competitive, but considerably less formidable among those with a four-year degree, 37 percent of whom he won, and those with post-graduate credentials, only 29 percent of whom voted for him.

Likewise, he ran noticeably better among those earning less than $50,000 than those earning more. Gender mattered too: Through the first 25 exit polls, Trump’s support from men ran eight points higher than his backing from women. Ideologically, he performed best in the center of the party, posting better numbers among moderate and somewhat conservative voters than he did among those who identified as very conservative. Measured by age, Trump ran noticeably better among voters older than 45 than those who were younger. His performance among evangelical Christians almost exactly equaled his overall share of the vote. And for all the chatter that Trump had won by importing new voters into the GOP process, he actually posted higher numbers among self-identified Republicans than Independents, the POS analysis found.

Cruz, who emerged as Trump’s main rival, generated a much narrower coalition of support. According to the analysis, he beat Trump only among one major group: voters who identified as “very conservative.” Cruz trailed Trump among men and women, all age groups, and all education levels, though he came much closer to him among those with a post-graduate degree. He lost both Republicans and Independents by 13-percentage-point margins. Cruz even trailed Trump among white evangelical Christians, his supposed foundation, by over seven points, the POS analysis found. And where Cruz was weak, he was very weak. He carried barely more than one-in-five voters who identified as “somewhat conservative,” and only about one-in-seven who considered themselves “moderate” or “liberal.”

One particular key for Trump was his success among evangelical Christians without a college degree. Trump’s margin over Cruz among those blue-collar evangelical Christians led to his victories in southern states including South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, and Mississippi, as well as Midwestern battlegrounds including Michigan and Indiana, where Trump won 55 percent of these voters on Tuesday night. Cruz’s inability to hold those blue-collar evangelicals doomed his hopes of building a solid regional base in the South and left him facing a deficit after Super Tuesday on March 1 that he never could surmount.

The greater breadth and consistency of Trump’s coalition is even more apparent when viewing the exit polls on a state-by-state basis. Looking across the exit polls of 26 states, Trump carried seniors in 19 states; self-identified Republicans in 20 states; men, “somewhat conservative” voters, and those aged 45 to 64 in 21 states; whites without a college degree and moderates in 22 states; and those who did not identify as evangelical Christians in 23 states. The sweep of those victories underscored the unusual extent to which Trump succeeded in recreating his winning coalition across all geographic regions. Trump’s margins among his best groups were often commanding: He carried at least 45 percent of white voters without a college degree in 17 states with exit polls, including many who voted early in the primary season when the field was much more crowded. He reached at least 45 percent among males voters in almost half of the exit-polled states.

By contrast, Cruz carried only a single major group in a majority of the states where exit polls were conducted: self-identified “very conservative” voters, who preferred him in 14 states. He won men and whites without a college degree in only four states and self-identified Republicans in five. Even evangelical Christians preferred Cruz in just seven states, compared to 17 for Trump. Cruz only won “somewhat conservative” voters in two states, Texas and Wisconsin, and moderates in zero states—his support among this group did not reach even double digits in ten states. Perhaps most importantly, he carried voters who did not identify as evangelical Christians only in Wisconsin. Particularly in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, Cruz attracted only negligible numbers of voters who were not evangelical Christians: He won 8 percent of non-evangelicals in New Hampshire, 9 percent in Massachusetts, 11 percent in Connecticut and 12 percent in both Maryland and New York.

The fundamental premise of Cruz’s campaign was that he could do what Mike Huckabee could not in 2008 and Rick Santorum could not in 2012: reach beyond social conservatives to build a coalition that also attracted significant numbers of economic conservatives. In that, Cruz fundamentally failed.

Some GOP groups displayed considerably less enthusiasm than their peers about Trump throughout the process. He won women in 17 of the states with exit polls, white college graduates in 13 (while tying with Cruz in another), and those under 30 in just 11 states, although only 21 had enough to measure in exit polls. Trump notched several of those victories only in his final sprint to the finish line after New York.

But no one else ever showed enough reach to consolidate the voters most resistant to Trump. Just as Cruz remained overly dependent on evangelicals and the most conservative voters, John Kasich never expanded beyond a beachhead among moderate suburbanites. If Kasich and Cruz proved too narrow in their reach, Marco Rubio proved too shallow. Before he quit the race, he drew support from across the party, but not enough from any camp to win more than a single state—Minnesota, which he carried along with contests in Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia.

As these alternatives faltered, Trump continued to chug forward, showing remarkably similar strengths and weaknesses in all regions of the country through early April. And when he achieved his big victory in his home state of New York last month, resistance splintered like a medieval gate surrendering to a battering ram.

Now, Trump has routed all of the GOP leaders who have disparaged, feared, and pushed back against him. He has shifted the party’s balance of power: away from the white-collar and upscale voters who largely nominated John McCain in 2008 and Mitt Romney in 2012, toward the party’s more populist and turbulent working-class wing. In the process, he is steering his party into uncharted electoral waters, on a journey that few of its leaders expected, but many feared, when Trump first descended down the escalator to declare his candidacy last summer.

(Top image via Flickr user Gage Skidmore)

Leah Askarinam contributed reporting.