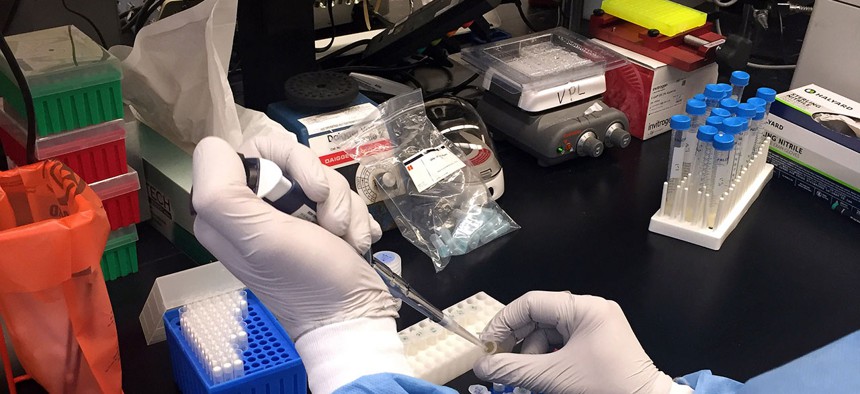

A Zika virus researcher at the NIAID Vaccine Research Center pipets samples in April. NIAID

Was a Senator’s Report on Waste in Federal Science Grants More Wasteful Than the Research Itself?

Scientists and agency officials say Hill report does not present a full and accurate picture of their projects and the merits of their work.

When a federal agency spends $1.1 million to fund research into whether and why female cheerleaders look more attractive when together with other female cheerleaders, it is likely to raise some eyebrows. For Sen. Jeff Flake, R-Ariz., it was a real head-scratcher.

The senator earlier this month released a report that questioned seemingly outrageous research projects funded by the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health and other federal agencies. The evidence from his own research was clear, Flake posited: the studies were a microcosm of flagrant government waste, evidence of a bureaucracy run amuck when left to its own devices.

“We ought to reevaluate a system that spends federal funds looking for America’s next top model over a cure for cancer,” Flake said from the Senate floor when releasing his report. “When federal agencies don’t spend our limited research dollars wisely, they’re not just wasting money, they’re missing opportunities, and we can’t afford either.”

As for the cheerleader project specifically, Flake wrote in the report, “Let’s face it, this study is an ugly waste of tax dollars, no matter how you look at it.”

Of course, scientific research, unlike information manipulated by politicians with ideological agendas, is rooted in truth. And the truth of the cheerleader study, according to NSF, is it cost $4,000 and was the summer project of students at the University of California. The $1.1 million referenced by Flake refers to the grant provided to a three-year project at multiple universities to study semiautonomous driving. Studying the “cheerleader effect” was part of the researchers attempt to embed human cognitive phenomena into predictive, self-driving technology.

In other cases, researchers were confused how Flake even arrived at his numbers. The senator said a study into how “disgust sensitivity” varies by political ideology cost NSF $855,000. Kevin Smith, chair of the political science department at the University of Nebraska and author of the report on the study, told Government Executive that figure represented the cumulative total of federal grants he and his research team received over the last decade for “dozens of studies.”

Smith’s study used photos of worms -- including one in which a man was placing a handful of worms into his mouth -- to provoke disgust, and measured how the responses differed based on political ideology. The research was so unnecessary, Flake said, it was “likely to unite both Republicans and Democrats in disgust.”

The researcher took issue with that assessment, however, saying there is inherent value in “biological and psychological underpinnings in differences in political behavior.”

We are living in a time of “extreme political polarization,” Smith said. “Figuring out how these differences exist and how we might bridge them we think is an interesting question.”

In some cases, he added, ideology can lead to the “ultimate expression of political beliefs.”

In some parts of the world “people are literally killing each other for abstract political beliefs,” he said. “Why are they doing that? Is there a way to deter them away from doing that?” Adding to the problem, Smith said, was that no one from Flake’s office ever reached out to solicit an explanation.

Jason Samuels, a Flake spokesman, said the researchers were welcome to respond to the report “as they see fit.” He added, “The stated purpose and potential benefits of each study were considered before being included in the report.”

Flake’s office also did not contact NSF, said Aya Collins, an agency spokeswoman.

“What’s more wasteful than to have to research and pull things together when we can easily provide staffers on the Hill with information?” Collins asked.

Rouslan Krechetnikov, a researcher and professor at the University of California Santa Barbara, whose study on why people walking with coffee spill the beverage was cited in the report, expressed a similar sentiment.

“If Sen. Flake prepared his non-substantiated report while being financially supported by federal funding, then the irony is that it might be him who wastes taxpayers’ money,” Krechetnikov said (Samuels said the report required “no additional cost” to compile). Krechetnikov added Flake’s cherry-picked quotes from media coverage of this study represented a “biased” and “non-professional” attempt to support “his very subjective point of view.”

Meanwhile, Krechetnikov said, he used no federal funds received from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency for the study, but included it in a report to DARPA because he was considering using his grant to further the research.

Collins said NSF gives out thousands of grants annually, and the agency takes seriously its responsibility to ensure they are wise investments.

“Supporting exceptional science and engineering research and responsible stewardship of taxpayer dollars are two duties that NSF considers critical,” she said, “and complementary.”

Additionally, Collins noted the grants go through a rigorous merit review process before they are awarded, with screening from at least three “science and engineering experts” who do not work for NSF and are “well-versed in their particular discipline or field of expertise.” The competition is “intense,” she said, with only one in five applicants receiving federal funds.

Successful applicants demonstrate “intellectual merit,” meaning the research can potentially advance knowledge, and “broader impacts,” meaning in can achieve “specific, desired societal outcomes.”

Smith, for example, said his grant proposals are turned down more often than they are accepted.

Michael Lauer, NIH’s deputy director for extramural research, said his agency’s grants are awarded “based upon scientific merit, public health needs, programmatic priorities, scientific opportunities, portfolio balance and budgetary considerations.”

NIH grant applicants go through a two-step process, first through the Scientific Review Group and then the Institute and Center National Advisory Councils or Boards. The former group is made up primarily of non-federal scientists in the relevant field, while the latter consists of public and private representatives with expertise or interest in health and disease. If both of those entities favorably recommend providing a grant, then the appropriate NIH institute or center can decide to make the award based on its research priorities.

Flake issued his report, and a corresponding bill to bring more oversight to federal science grant funding, in the midst of a congressional debate over how to fund Zika research and prevention efforts. Samuels acknowledged the specific dollar amounts allotted for each study mentioned in the report were not publicly available and the totals included could therefore represent larger projects. Flake’s bill, he said, would bring more transparency to that process.

The report still highlights the collective $35 million cost of all the larger research projects from which the studies contained therein were funded. Flake said that money could have been better spent as part of the $1.9 billion in emergency funding the Obama administration requested to prevent the spread of Zika, rather than “wasteful” research.

Lauer, however, noted scientific breakthrough does not always come from the most obvious research.

“While it may be easy to make light of research studies such as those mentioned in this report,” Lauer said, “recall that many great scientific discoveries started with work that may have seemed irrelevant to human health.”

The discovery of the drug Warfarin, a drug used to prevent the formation and growth of blood clots, occurred because researchers studied cattle that ate moldy clover, he noted as one example.

David Hu, a professor at Georgia Tech with a Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, defended his work in a public post in Scientific American. He said his research on how animals are able to shake themselves dry -- cited in Flake's report -- could help find more efficient ways to get moisture out of clothing or prevent dust collection that makes solar panels less productive. Additionally, Hu noted, the survey could help educate students on topics like centripetal force.

“I enjoy doing research,” Hu wrote. “I don’t try to hide it. Scientists are human beings with intrinsic interests, but we aren’t here to solely serve the public. We also have hunches when we’re onto something big. Sometimes we have to take left turns to get to a place faster. Solving difficult problems like green energy often requires revolutionary approaches.”

Still, he did not resent Flake for his report.

“Asking questions about wastefulness is an important activity. Is it wasteful or not?” he asked. “Like all research questions, this one should continue to be asked again and again.”

Smith too said he values questioning of how agencies spend their money.

“I’m a taxpayer too,” he said. “I’m incredibly conscientious about the need to be a good steward of taxpayer money.” He added, though, “Going about it this way, this isn’t a debate.”

He also expressed concern about the fallout that may stem from the report.

“Whenever we apply for a grant for a federal agency, are those federal agencies going to hesitate [because we were] called out by a U.S. senator?” he wondered.

If science agencies stop funding research without obvious outcomes, NSF’s Collins said, the consequences could be more dire than questionable disbursement of taxpayer dollars.

“The most wasteful thing is wasted opportunity,” she said. “It is most wasteful for NSF not to stay true to its mission.”