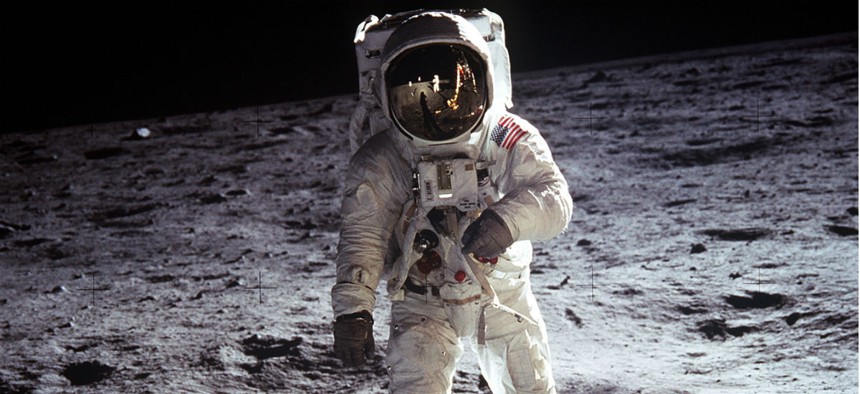

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin explores the surface of the moon during the Apollo 11 mission. One of the items NASA lost was an Apollo 11 lunar collection bag that contained lunar dust particles. NASA file photo

Space Agency Failed to Track All Historic Artifacts, Watchdog Finds

Private citizens beat feds to the punch at profitable auctions.

NASA, as one of government’s most storied pioneer agencies, needs to better archive its historical artifacts, according to a watchdog’s latest audit.

A jarring example, according to a report released on Tuesday: “Poor recordkeeping contributed to NASA losing possession of an Apollo 11 lunar collection bag that contained lunar dust particles.” According to court records, in 2003 the bag was seized by the FBI from the home of the CEO for the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center during a criminal investigation.

A federal judge authorized the U.S. Marshals Service to sell the bag, and in 2015, a private citizen purchased the bag at a government auction for $995, subsequently submitting the object to NASA for authentication.

NASA in 2016 confirmed that this was the bag that flew on Apollo 11 and decided to keep it and reestablish custody. But in December 2016, a federal judge ruled that the sale to the citizen was legitimate, the report said, so the agency returned the object.

In July 2017, it sold at auction for $1.8 million.

The IG’s audit of NASA’s record-keeping examined agency handling of its historic real property (buildings, structures and test sites) around the country, and its personal property (cameras, spacesuits and mission logs). Proper inventory and audit practices must comply with the National Historic Preservation Act and guidance from the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board.

For the past eight years, NASA’s IG has cited aging infrastructure as a major agency challenge, which spills into its record-keeping and preservation of historic assets. For this recent report, its staff interviewed NASA officials and contractors, as well as preservation experts at the Smithsonian Institution.

“NASA’s processes for loaning and disposing of historic personal property have improved over the past decades,” the IG wrote, “but a significant amount of historic property has been lost, misplaced or taken by former employees and contractors due to the agency’s lack of adequate procedures.”

Too often, the report said, a “reluctance” to assert an ownership claim and a lack of established procedures has made the space agency slow off the mark.

In one case, a U.S. Air Force historian noticed what he thought was a NASA prototype Lunar Rover Vehicle in a residential neighborhood in Alabama and reported his sighting to NASA. The agency referred the information to the inspector general, who contacted the individual owner and asked NASA to make plans to accept the vehicle back as a donation. But “after waiting for more than four months for a decision from the agency,” the report noted, “the individual sold the rover to a scrap metal company. NASA officials subsequently offered to buy the rover, but the scrap yard owner refused and, realizing its historical value, sold the vehicle at auction for an undisclosed sum.”

Auditors found NASA’s procedures for managing heritage assets are “often in conflict with other procedures, are vague, and do not adequately describe the processes intended to identify and preserve the assets.”

Finally, the IG suggested that NASA may not be the best agency to handle such preservation decisions, given the need for storage in special temperature-controlled facilities.

In recommendations, the IG identified improvements NASA can make in procedures for securing debris collected from the space shuttles Challenger and Columbia disasters and loaning them out to education groups.

The IG also recommended improved processes for identifying historic artifacts and better coordination with other agencies for recovering and managing them while also reviewing leases to maximize disposal of unneeded properties.

NASA managers agreed with most of the recommendations, but argued that the agency’s existing policy on facilities leases is already aligned with the law.