Consider this too: Lincoln’s assassination had put his vice president, Andrew Johnson, in the White House; the country thus had no sitting vice president. Should Johnson be convicted and removed from office, then, the president pro tempore of the Senate was next in line for the job, per the Presidential Succession Act of 1796. (Today, the Speaker of the House would be next in line—and just imagine how senators might vote if they thought Speaker Pelosi would sit in the Oval Office.) Senators wanted to know whether Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio, the president pro tempore, should be allowed to vote for Johnson’s conviction, because Wade’s future would be directly affected. But Johnson’s son-in-law was Senator David Patterson of Tennessee; wasn’t this a conflict of interest too? Yet if the Senate during the trial was still understood to be a legislative body, not a court, then each state was certainly entitled to the vote of its two senators, which is what was eventually decided.

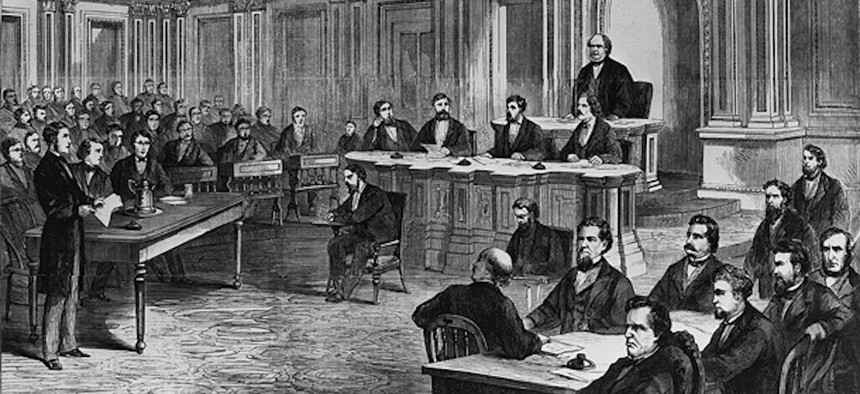

A scene from the impeachment of Andrew Johnson as shown in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper March 28, 1868 U.S. Senate

How to Conduct a Trial in the Senate

The Constitution does not provide procedural guidelines for how an impeachment trial is to be conducted—so the senators of 1868 had to figure it out as they went.

On Thursday, March 5, 1868, Chief Justice Salmon Portland Chase, dressed in his long black-silk robe, marched to the head of the Senate chamber and solemnly announced that “in obedience to notice, I have appeared to join with you in forming a Court of Impeachment for the trial of the President of the United States.” Swearing that he would serve impartially as judge during the trial of President Andrew Johnson, he also said he would faithfully administer the Constitution and the laws. No one quite knew what that meant. They still don’t.

Impeachment: People know the House of Representatives may impeach a sitting American president with a majority vote. They also know that the Senate then conducts a trial of the impeached president with the chief justice presiding, and if two-thirds of the Senate vote to convict, the president will be removed from office. But the United States Constitution does not provide procedural guidelines for how that trial is to be conducted—what constitutes evidence, for instance, or who may object to it, or who might testify for or against the president. And in 1868, after the House of Representatives voted to impeach Andrew Johnson, these issues were fiercely contested in the Senate trial.

President Johnson had fired his secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, without the Senate’s consent, which the recently passed Tenure of Office Act had required. Though constitutionally dubious, that law had been created precisely to prevent Johnson from obstructing justice by sacking such men as Stanton, who was helping Congress implement the Reconstruction Acts, which Johnson had also been attempting to obstruct. When President Johnson violated the law, the House voted overwhelmingly to impeach him. It then drafted 11 articles of impeachment, most of which dealt with Johnson’s violation of the statute—his apparent commission of a demonstrable crime—although he was also accused of denying the legitimacy of Congress, holding it in contempt, failing to execute its laws, and abusing his power.

The 11 impeachment articles were submitted to the Senate, but beyond stipulating that each chamber of Congress define the rules of its own proceedings, the Constitution did not dictate what would or should happen during an impeachment trial, or even how to organize it. So Chief Justice Salmon Chase seized the day. Chase had been a political heavyweight for decades, first as a noted lawyer for fugitive slaves and then as a senator, governor, and presidential contender from Ohio before Abraham Lincoln tapped him to be Treasury secretary and, after the death of Chief Justice Roger Taney in 1864, nominated him to the Supreme Court. A founder of the Republican Party who was deeply suspicious of its progressive wing—the wing that most desired Johnson’s conviction—Chief Justice Chase was a man convinced of his own probity. He told the Senate that in case of a tie, he wanted to be able to cast a vote.

To prosecute Andrew Johnson, the House had elected seven members, called managers, who quickly argued that precedents both in England and in the United States suggested that the presiding officer, even when a member of the deciding body, had no more rights than the House did. And if that presiding officer were not a member of the body, as the chief justice was not, because he was not a senator, he should not then be allowed to vote. He could merely submit questions to the larger body, not answer them.

But that argument implicitly raised yet another issue: whether the Senate during the trial should be organized as a court of law. If the Senate operated as a court, the chief justice would be able to exercise certain leverage, such as ruling on the admissibility of evidence or the reliability of witnesses. Was this judicial meddling, as some argued? Chief Justice Chase’s conditions—that as presiding officer, he should maintain control over the proceedings—were deemed an attempt to derail the entire process. It was no secret that Chase regarded the impeachment resolution against Johnson to be absurd, even though he didn’t much like the president. What’s more, Chase had his own eye firmly fixed on the Oval Office, and his overweening ambition made his impartiality suspect, because he was said to believe that Johnson’s acquittal would serve his own presidential prospects in 1868.

Conducting the trial of the president mostly as if it were a legal proceeding raised other questions, having less to do with procedure or even the chief justice’s presidential aspirations than with how the president’s guilt might be adjudicated. That is, conducting the trial as if it were a legal proceeding slanted the definition of impeachable offense toward a criminal breach of the law and away from questions of fitness, folly, or abuse of power. The House members prosecuting the president argued that because an impeachment trial takes place in the Senate, not in a judicial court, the trial wasn’t subject to a judicial court’s restrictions, say, regarding conviction—namely, certainty of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. And, they said, the president need not have violated a specific law to be found guilty of malfeasance. Such is the broad interpretation of an impeachable offense, as Alexander Hamilton defined it in The Federalist Papers: Impeachment should “proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust.”

The Senate thus faced tricky problems, and because there was no blueprint for the trial of a sitting president, there was something improvised about its solutions. After long debate, the Senate did concede a great deal of its authority, concluding that the chief justice could decide on the admissibility of evidence; however, it also stipulated that an individual senator could call for a vote on any of his rulings. And the chief justice was in fact allowed to cast a tie-breaking vote on two procedural questions; a motion to prevent him from casting such a vote was defeated.

Still, there were other issues to consider: For instance, would the president be compelled to appear? Johnson was not. In fact, his lawyers made sure of that, so fearful were they of what the pugnacious, scrappy chief executive might say, because he was already known for calling his enemies traitors and in some cases suggesting they be hanged. Instead, the president’s far more dignified lawyers replied to the summons.

In other words, no one knew beforehand what dilemmas or questions would arise. There was no way to anticipate all of them, and the 54 senators could only hash them out as best they could. No one was thinking of impeachments down the road, although the Senate’s procedural decisions were more or less codified in “The Rules of Procedure and Practice in the Senate When Sitting on Impeachment Trials” and placed in the Senate Manual; these procedures were not updated again until 1974, after Watergate. Congress plainly had not undertaken impeachment quickly and did not take its execution lightly, and if the trial was halted more than once by delays and seemingly interminable arguments about procedure, those arguments were inevitably inseparable from the question at hand: whether Andrew Johnson had committed impeachable offenses and should be removed from office.

Determined to do the right thing and, if necessary, rid the country of an unfit president, the Senate proceeded in an orderly, if improvised, fashion. It intended to preserve the nation and its values, even right after a war, and without causing another one. And so it did. That preservation, that system, that belief—in the rule of law, in the ability to determine its parameters—is the considered vision it bequeathed to us.