Andrew Park / Air Force

Trump Wants the National Archives to Keep His Papers Away from Investigators – Post-Watergate Laws and Executive Orders May not Let Him

Donald Trump’s lawsuit to stop the release to Congress of potentially embarrassing or incriminating documents puts the National Archives in the middle of an old legal conflict.

The National Archives is the United States’ memory, a repository of artifacts that includes everything from half-forgotten correspondence to the paper trails that document the days of the country’s life. The National Archives contains such items as bureaucratic correspondence, patents and captured German records. It holds Eva Braun’s diary and photographs of child labor conditions at the turn of the 19th century.

Most of the time, the National Archives goes on with its work with little attention. But right now it is at the center of a political fight about the public’s access to the papers of former President Donald Trump.

That battle is being fought by Trump against President Joe Biden and the House committee investigating the Jan. 6 insurrection. The legislators want to see Trump administration records that are housed in the National Archives, Biden has said the archives should provide them – and Trump has sued the committee and the archives to stop the papers from being divulged to Congress.

What materials should be kept, where they should be kept and, in the case of presidents, who owns and controls them have long been a thorny question for the nation. Historian John Franklin Jameson pointed out that from 1833 to 1915 the U.S. had 254 fires in federal buildings – with important public records consumed by the flames. Fire, bugs, mold, water and vermin were all persistent threats that ate away at the country’s earliest materials.

Jameson, along with others, pushed for funding a National Archives in the early 20th century. The formal organization known today was created by Congress in 1934. From that time, “all archives or records belonging to the Government of the United States” were to be under “the charge and superintendence” of the national archivist.

Currently, the National Archives is home to 12 billion sheets of paper, 40 million photographs, 5.3 billion electronic records, and untold miles of video and film. Among those materials are the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, military and immigration records and even the canceled check for the purchase of Alaska.

At the center of the current conflict between Trump and the congressional committee is the status of presidential papers: Are they public or private?

The archives have long dealt with this question. President George Washington took his papers home with the intention of creating a library, but it never materialized. In fact, rats ate many of Washington’s records.

Washington had established the idea that the president’s papers were his property, since he had written or created them. Many other presidential families who didn’t like the contents of their relation’s presidential records disposed of or burned them, leaving only a slanted picture of the actual history.

The situation continued until the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was the first to assert presidential papers should be preserved for future generations. He considered presidents stewards, not owners, of their materials. The wealthy Roosevelt privately built a facility and then donated the papers and collections to the National Archives.

Roosevelt’s library sparked public awareness of these papers, and by the late 1940s the question about what the country should do with the president’s papers came to a head. Roosevelt’s successor, Harry Truman, was hesitant to make all his records fully public property, but he also was appalled to find out how many predecessors’ records had been intentionally destroyed.

“Such destruction should never again be permitted,” said Truman in 1949. “The truth behind a president’s actions can be only found in his official papers, and every presidential paper is official.”

The Presidential Libraries Act was passed by Congress in 1955. It allowed private construction of locations to house presidential papers, but those libraries would be maintained by the national government. The presidential documents were still considered the private property of their chief executive, though most donated them to their libraries.

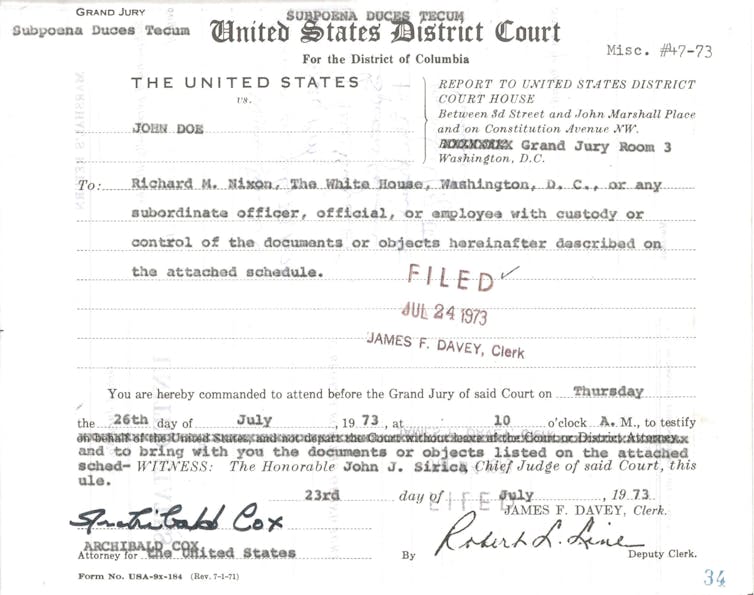

In 1974, the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act was enacted to prevent the destruction of President Richard Nixon’s materials in the wake of the Watergate scandal. In 1978, passage of the Presidential Records Act settled the question of ownership over presidential records: They were the property of the American public. As soon as a president leaves office, all records move immediately to the custody of the national archivist.

The 1978 legislation stated that duplicate or truly nonrelevant records can be disposed of, but only after consultation with the archivist of the United States. In 2014, this act was updated to also include electronic records.

Much of my academic career as a political scientist rests upon the availability of these documents. My dissertation and first book both look at locations of presidential speeches. If presidents can speak anywhere, what can we learn about their priorities from these choices? Public documents made my research possible. Without them, no comprehensive accounting of presidential speeches would exist.

Presidential records have occasionally stirred controversy. Many presidents have sought to shield possibly embarrassing or controversial information from public view.

During Watergate, investigators sought potentially incriminating materials from Nixon. He claimed he had an absolute executive privilege and could withhold any communication from the legislative and judicial branches.

Executive privilege allows current presidents to provide notice to the National Archives to withhold any materials unless told to do so directly by them or court order.

The Supreme Court sharply disagreed with Nixon’s sweeping executive privilege claim in a unanimous opinion in 1974, stating, “Neither the doctrine of separation of powers nor the generalized need for confidentiality of high-level communications, without more, can sustain an absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances.” Nixon’s records had to be released.

In 2001, President George W. Bush, building on efforts of President Ronald Reagan, sought to create a formal process to manage claims of executive privilege. Bush’s change was controversial because it allowed sitting and former presidents the ability to almost indefinitely shield information and also allowed a former president to appoint a representative to assert on their behalf even after their death.

Barack Obama revoked Bush’s order the day after he was inaugurated in 2009.

Obama’s 2009 order guides current policies. Any claims of executive privilege involve consultations with the archivist, attorney general and president’s counsel. Other executive agencies may also be involved if the information affects them.

[Over 115,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

How the policy applies to former presidents is trickier. Those who want executive privilege to prevent disclosure of documents – as Trump does – must rely upon the current administration for the final decision. They do not have the ability as former presidents to assert blanket executive privilege.

For other presidents, such as George W. Bush and Barack Obama, executive privilege was implemented as a tool to stall investigations. Trump’s attempt to use it may be a delaying tactic, which may benefit him in the short term. But it could also cement the limitations the Supreme Court put on a president’s power to invoke executive privilege. If, in considering the Trump case, the court reaffirms the Nixon ruling, that would be a reaffirmation that the president’s power to keep documents secret was not absolute.

![]()

The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.