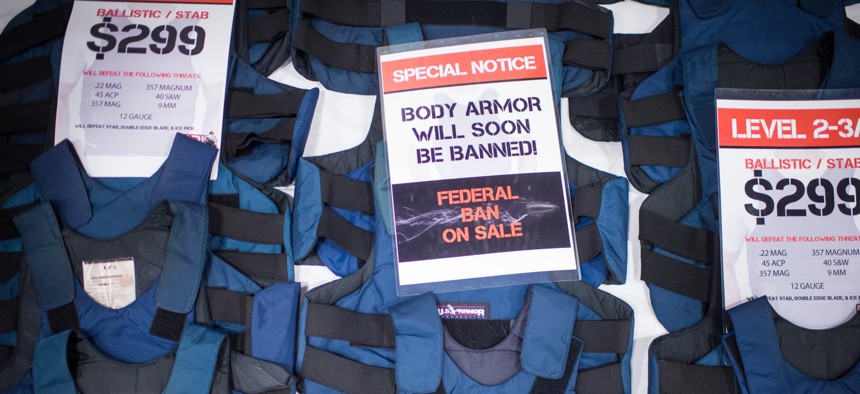

Body armor is seen for sale in 2015 in Virginia. Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post via Getty Images

After Mass Shootings, Lawmakers Weigh Body Armor Bans

Over the past 20 years, sales of body armor have grown steadily among the general population.

This story was originally posted by Stateline, an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.

BUFFALO, N.Y.—Calls for new gun restrictions inevitably follow most American mass shootings, including the one that killed 10 people at a Buffalo supermarket six weeks ago. But in the wake of the Tops supermarket massacre, legislators here and in several other states also have turned their attention to a new target: civilian body armor.

Such equipment—including helmets, bulletproof vests and armor plates—is designed to protect soldiers and law enforcement officers in the line of duty. Until recently, however, no state but Connecticut had restricted how ordinary citizens buy and sell military-grade tactical gear. The armor has, critics say, empowered violent criminals—including mass shooters—to return fire at law enforcement and extend their rampages.

Over the past 20 years, sales of body armor—like sales of guns and ammunition—have grown steadily among the general population, said Aaron Westrick, a professor of criminal justice at Lake Superior State University who has worked extensively with body armor companies and law enforcement. That has complicated some procedures for police officers, who now must train to shoot around body armor, and alarmed some lawmakers and advocates, who question why so many Americans now own tactical gear intended for combat.

In Buffalo, a bulletproof vest allowed the accused 18-year-old gunman to continue his attack even after being shot by a store security guard, retired police officer Aaron Salter Jr. Salter was among those killed. According to the Violence Project, a nonpartisan research center, 21 mass shooters in the past 40 years have worn body armor.

“The shooter in Uvalde had it, in Buffalo, in Aurora, in Boulder, in Sutherland Springs,” New Jersey state Sen. Joseph Cryan, a Democrat and former county sheriff, said of the Tops shooting and other massacres in Texas and Colorado. Cryan’s proposed civilian body armor ban is in committee. “Why do we have to wait for another one?”

New York passed the nation’s first body armor ban June 6; it is a narrow prohibition on soft body vests that legislators have said they will soon expand. New York’s ban earned votes from both parties, though 46 of the 63 Republicans in the legislature opposed it. Pennsylvania Democrats also have promised to introduce body armor legislation this session. On June 16, three of New York’s U.S. representatives—two Democrats and a Republican—introduced a bill to nationally bar the sale of high-performance body armor to civilians.

Already, however, these measures have proved deeply controversial. At least one body armor manufacturer has promised to sue New York, arguing the state has no right to outlaw protective equipment.

Even among researchers who study gun violence, there’s some doubt that restrictions on body armor sales will make shootings less deadly or less frequent. Instead, Democratic lawmakers have sometimes described the bans as a kind of policy fallback: Given the deadlocked politics of gun control, they’ve said, regulating body armor is one rare area of possible bipartisan consensus.

“Mass shootings are horrific—don’t get me wrong—but they’re such an insignificant part of the violence we’re confronting,” said Warren Eller, a public policy professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “The probability of having an armed offender wearing a body vest get into a firefight with law enforcement is really, remarkably insignificant.” Guns killed more than 45,000 Americans in 2021, according to the Gun Violence Archive, a nonpartisan data collection group. Only 705 of those deaths took place during mass shootings.

Few Existing Restrictions

Lawmakers have attempted to regulate body armor before, but without much success. In 2019, Democratic U.S. lawmakers in the House and Senate proposed two separate, federal body armor bills that never made it to a vote. New York state also has repeatedly considered, but never adopted, a proposal to create a central registry of body armor sales and distributors.

This time, however, proponents have been bolstered by the back-to-back tragedies in Buffalo and Uvalde, Texas, where both gunmen wore some type of tactical gear. In Buffalo, a set of law enforcement-grade hard armor plates saved the shooter from a bullet that police say might have ended his attack much earlier. In Uvalde, the gunman wore a plate carrier vest without its bulletproof inserts—a nonprotective get-up that some legislators have nonetheless said illustrates the threat of mass shooters and body armor.

In addition to Uvalde and Buffalo, shooters recently wore bulletproof vests during the 2015 attack on a county Christmas party in San Bernardino, California, that killed 14 people; the 2017 attack on the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, that killed 26; and the 2019 attack outside a Dayton, Ohio, bar that killed nine.

Some rioters who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, also wore body armor, a fact reinforced by testimony in a House congressional hearing this week that recounted Secret Service concerns about then-President Donald Trump’s security at a rally that day.

“We shouldn’t be giving civilians equipment that makes them think they can get in a firefight and return fire,” said Adam Skaggs, the chief counsel and policy director at the Giffords Law Center, which advocates for gun safety legislation. “When you give people all this tactical gear made for offensive tactical assaults, it’s not a surprise when some percentage of people use it for the purpose it was designed for.”

Few laws restrict civilians’ rights to buy or own body armor. Federal law prohibits people with violent felony records from owning it, and in many states, people who wear body armor while committing certain crimes can receive longer prison terms or lose the opportunity for parole. Connecticut also bans online body armor sales, requiring such transfers to happen in person.

In an online diary, the Buffalo gunman wrote that he bought his armor plates on a manufacturer’s website and his carrier vest on eBay.

In the absence of stricter regulations, body armor vendors and manufacturers have been left on their own to decide how to vet their customers, if they vet them at all. Some companies require that buyers provide a reference, a reason for purchasing tactical gear or a copy of their government-issued identification.

But it’s far more common for manufacturers who market to civilians to sell openly and to anyone, much like any other retailer, said Willie Portnoy, the vice president of sales and marketing at the body armor maker Buffalo Armory.

“All types of companies sell on the internet, or to anyone who has a credit card or cash in hand,” said Portnoy, whose company does not sell to civilians. “That is not something we’re comfortable with. … We don’t want to run the risk of a bad actor using our product for ill intent.”

An Unlikely Deterrent

Body armor bans seek to minimize that risk by criminalizing the sale or possession of civilian body armor, with some narrow exceptions for people whose jobs require it. In both New York and New Jersey, it will fall to either the attorney general or the department of state to determine which occupations qualify.

But the legislation has drawn questions and criticisms—and not only from Second Amendment groups, who have argued that body armor restrictions impinge on Americans’ rights to protect themselves. Although New York Democratic Gov. Kathy Hochul touted her state’s legislation as a response to the Buffalo shooting, the law omitted the type of body armor used by the gunman, an oversight that lawmakers have since said they will fix.

Several journalism organizations also have opposed the law because it may prevent reporters who cover protests, wars or other dangerous situations from obtaining protective equipment. During a June 2 debate in the New York Senate, Republican Sen. George Borrello questioned why bulletproof vests shouldn’t be available to taxi drivers or people working overnight shifts.

In an interview with Stateline, Borrello argued that the measure would do little to prevent mass shootings or make them less fatal.

“This was a slapdash, last-minute bill they [wrote] because of the Buffalo shooter,” he said. “And the law they passed wouldn’t even address that.”

Experts agree that body armor bans are unlikely to deter mass shooters from using tactical equipment, or from reducing gun violence overall. Body armor is so widely available, and in such large quantities, that local bans will simply push buyers into neighboring states, Westrick said. Several manufacturers already have reported a jump in sales, and neither the New York nor New Jersey bills require current owners to surrender equipment, though the federal proposal would also outlaw body armor possession.

On top of that, only a tiny fraction of the more than 100,000 shootings that take place in the United States each year are committed by a perpetrator wearing body armor. There also is little evidence to suggest that people who are highly motivated to purchase tactical equipment will be dissuaded by the possibility of a misdemeanor, said Eller.

“These are meant to be deterrents, but they don’t work that way,” he said. “If you get a plate carrier and plates, that’s a couple hundred dollars. … If somebody’s decided to do that, they’re probably not someone who’s worried about consequences.”

In the current political climate, however, some Democratic lawmakers see body armor bans as one of the few gun safety policies they can get passed. On the national level, some Republicans also have signaled they’re open to body armor legislation.

U.S. Representative Tim Briggs, the Pennsylvania Democrat who chairs the House Judiciary Committee, is preparing to introduce a body armor bill that mimics New York’s. Briggs told Stateline that he began looking for more “creative ways” to address gun violence after the chamber’s Republican majority blocked universal background checks and other, more conventional legislative measures.

Briggs isn’t giving up on those policies, he said. But the attacks in Buffalo and Uvalde convinced him of the need for immediate action to prevent mass shooters from outgunning security personnel and law enforcement.

“We are at an inflection point,” he wrote in a memo seeking cosponsors for the ban, “where we either become part of the solution or we have blood on our hands.”