Michaelstockfoto/Shutterstock.com

Many Feds Are Uncomfortable Communicating by Email

Employees are more afraid of retaliation by bosses than disclosure, survey finds.

The House Select Committee on Benghazi’s subpoena for some of Hillary Clinton’s past emails comes as many federal employees profess to a wariness of online communication when addressing sensitive topics.

Perhaps for good reason. At a Jan. 27 hearing of the Benghazi panel, Rep. Lynn Westmoreland, R-Ga., tangled with State Department Deputy Assistant Secretary Joel Rubin, asking, “Do you think the State Department can share emails between employees that Congress can’t see?”

Another possible inhibitor for email users is the ongoing potential for future disclosure under a Freedom of Information Act request. Dan Gordon, the former administrator of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy, told Government Executive that over his years of government service he was always keenly aware of the possibility his emails could be disclosed under FOIA.

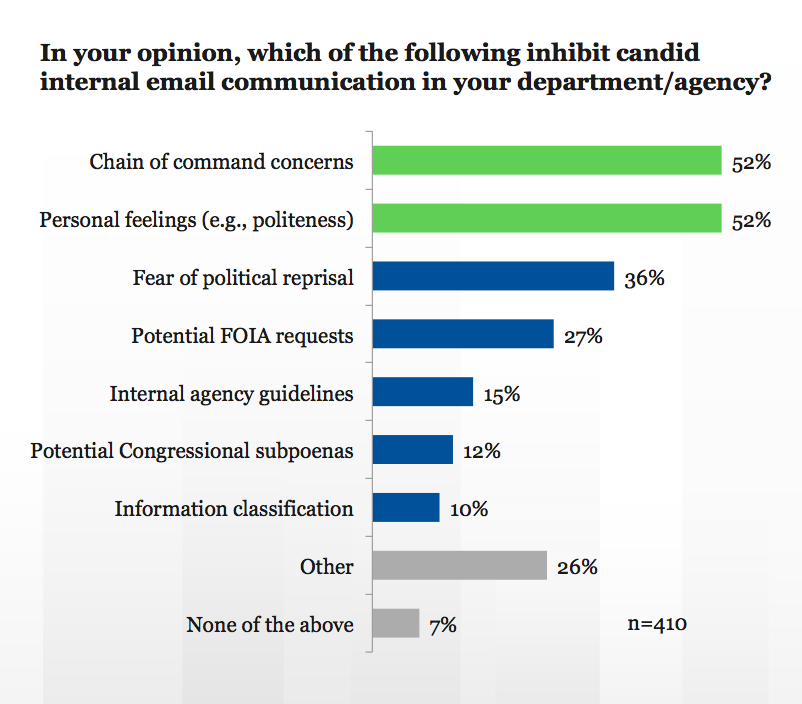

But a mid-February online survey of high-level agency executives by Government Business Council, Government Executive Media Group’s research arm, shows that fear of running afoul of the chain of command may be the most important reason executives avoid using email as productively as they might otherwise.

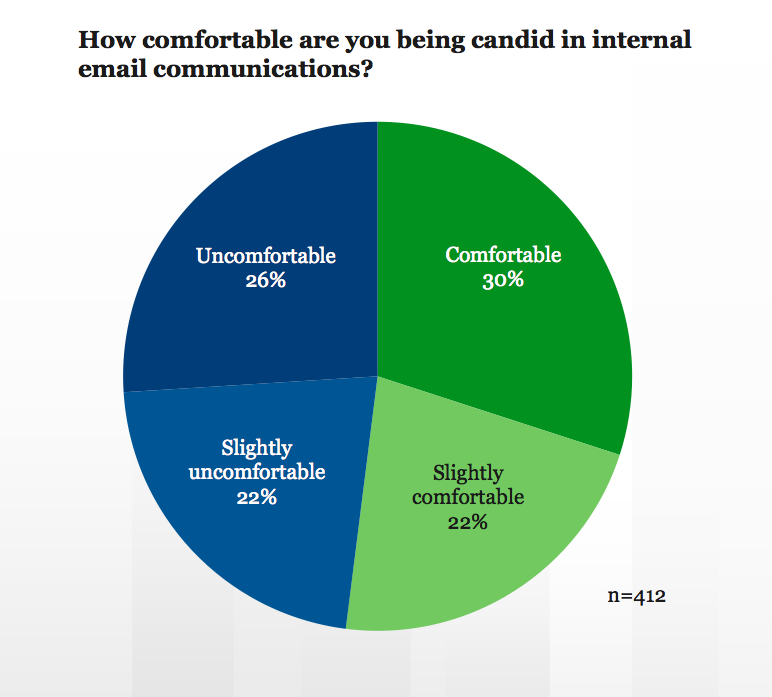

Nearly half of respondents, 48 percent, say they are uncomfortable or slightly uncomfortable being candid in internal email communications.

Just 30 percent say they are fully comfortable. Agency culture and rank make a difference. The percentage of those who feel uncomfortable or slightly so rose to 53 percent among non-Defense Department employees, compared with only 38 percent of Pentagon civilians. Respondents ranking GS-14 and above were less likely (43 percent) to feel uncomfortable being candid in emails, while 53 percent of those GS-13 and below expressed discomfort.

The top inhibitors among respondents were chain of command concerns (52 percent) and personal feelings, such as politeness (52 percent). Only 27 percent said potential FOIA requests inhibit such communication, and only 12 percent selected potential congressional subpoenas as the main inhibitor (26 percent selected “other”). Asked to specify, many cited some variation of reprisal from supervisors, bosses, or agency management.

“People are petrified to put anything, if they’re smart, in an email,” said a Homeland Security Department employee interviewed by Government Executive on condition of anonymity. “It’s pretty devastating if you do something perceived as being controversial. The higher level you are, the more you are concerned about in an email, almost to a point where you feel very inhibited,” the employee said, although the survey results suggest that senior executives are somewhat more comfortable being candid in email than mid-level executives.

Said another online: “The reason to refrain from communicating via email is more about the subordinate-supervisor relationship than policy.”

The result, said a third, is that “most people are afraid to be candid in an email because it can almost always be used against them in a performance evaluation. My motto has always been to pick up the phone and call someone and voice my opinion verbally . . . that way there is no paper trail.”

In the survey, 22 percent of respondents ranked GS-14 and above said congressional subpoenas inhibit candid email communication, compared with only 8 percent of those GS-13 and below. Pentagon employees (5 percent) were less likely to agree that the subpoena threat inhibited communication, compared with 16 percent of non-DoD respondents.

The same rank and agency differences emerged when respondents were asked about the effect of potential FOIA requests, with 44 percent of those GS-14 and up citing it as an inhibitor, compared with 20 percent of those at lower grades; thirty-three percent of non-DoD civilians expressed concern about FOIA disclosure, versus only 12 percent of Defense Department civilians.

The survey also revealed a mixed picture on knowledge of, and compliance with, the Federal Records Act and executive branch rules.

“We are sorely lacking in official records management practices,” said one respondent. But a majority indicated that all forms of communication or documentation listed could be considered federal records (though not all fit the government definition of “record”). More than 90 percent say emails, electronic documents and paper documents can be considered federal records. As many as 77 percent say so for instant messages, which fit the definition. But 64 percent say so for phone calls, which don’t meet the definition if not recorded, and 60 percent include social media posts, which can meet the definition.

As for agency compliance, 47 percent say they don’t know whether personal emails regarding government business are normally preserved for archiving in their agency; with 31 percent indicating they are not preserved.

Asked about the changing transparency environment, 33 percent indicated the number of records disclosures (due to subpoenas, FOIA requests) have increased over the last five years, while 52 percent said they did not know. Higher-ranked respondents, 48 percent among those GS-14 and above, said the number of disclosures has increased, compared with only 26 percent of those at GS-13 and below.

“My personal experience has been to use direct, face-to-face contact for the most honest and open conversations,” said one respondent online.

“I am careful what I write because I view email as something that can be looked at by IT or whomever,” said another. “Nothing is ever really truly private. I don't see this as a constriction to being candid. I see this as a way to save me from myself! It prevents me from saying something stupid in an email. If I want to express a harsh or candid opinion about a program that we have, it's better to discuss it over the phone. Talking about it ‘live’ helps show my tone or my intent.”

Another cited the need for “a healthy distrust of everybody -- you never know when someone can use something against you. My rule of thumb is that whatever I express in an email can be viewed by the general public.”

GBC posted an email-based survey on February 17, 2015, to a random sample of Government Executive, Nextgov, and Defense One print and online subscribers; 412 federal employees completed the survey, including those at the GS/GM-11 to 15 grade levels and members of the Senior Executive Service. Sixty-three percent of respondents are GS/GM-13 and above or the military equivalent. Respondents include representatives from at least 29 different departments and agencies, including each of the military services. Twenty-eight percent are DoD civilians. Margin of error is +/- 4.8 percentage points for our population.

(Image via Michaelstockfoto/Shutterstock.com)