Denis Rozhnovsky/Shutterstock.com

Will Donald Trump Dismantle the Internet as We Know It?

Open-web advocates are preparing for a renewed policy war as net neutrality’s future remains uncertain.

Talking about net neutrality is so boring, the comedian John Oliver once quipped, that he would “rather listen to a pair of Dockers tell me about the weird dream it had” than delve into the topic.

So it’s unsurprising that Donald Trump—an entertainer with a flair for the dramatic and little interest in wonky details—has stayed away from the issue almost entirely.

If you want to captivate a nation, discussing thorny telecommunications policy is generally a terrible way to do it. (For those who have managed to avoid reading up on net neutrality thus far, the term refers to open-web principles aimed at curbing practices that give certain companies competitive advantages in how people access the internet. The FCC formally established rules last year that allow the agency to regulate broadband the way it oversees other public utilities. Those rules ban internet service providers from throttling—or slowing—connections to certain content online, and prohibit providers from offering faster connections to corporations that can afford to pay for premium web services. The rules also discourage zero-rating—in which an internet service provider subsidizes a consumer’s cost of going online but often does so in exchange for a competitive advantage.)

Despite Trump’s prolific social media presence, the president-elect hasn’t demonstrated any real understanding of tech issues—net neutrality included. As a candidate, Trump never outlined a technology plan or platform. His discussion of cyber security on the campaign trail and in presidential debates was muddled and at times bizarre. (Remember his comments on the Democratic National Committee hack? “I mean, it could be Russia, but it could also be China. It could also be lots of other people. It also could be somebody sitting on their bed that weighs 400 pounds.”)

Nevertheless, net neutrality advocates are preparing for a renewed fight, operating on the belief that Trump will work to dismantle the internet as we know it.

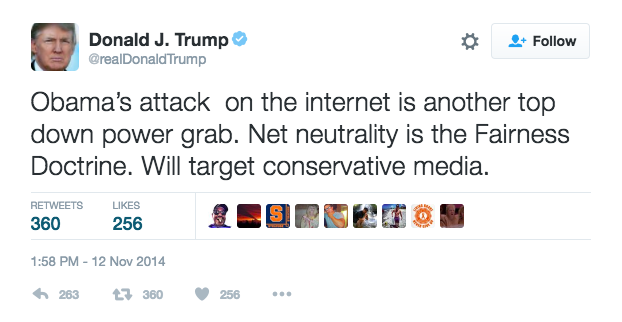

Trump’s main—and possibly only—public comment on net neutrality came in 2014, before he was officially running for president, in a bewildering tweet that seemed to conflate tenets of the open web with the Fairness Doctrine, a federal policy that required broadcasters to use airtime to discuss controversial issues of public interest—and to feature opposing views on those issues. (The rule was eliminated in 2011.)

Trump’s stance, incoherent though it may be, seems simple enough to parse anyway: the Obama administration advocated for net neutrality (and specifically for strong FCC regulation of net neutrality rules), therefore Trump opposes it. Plus, Trump’s a Republican; Republicans tend to oppose regulation.

There are other, more specific developments that have net neutrality advocates worried. The make-up of Trump’s FCC transition team is among the biggest clues that a reversal of federal policy is likely. His appointees include Roslyn Layton, Jeffrey Eisenach, and Mark Jamison, all of whom have argued against the existing net neutrality rules. Eisenach and Jamison have both worked for companiesfighting the rules—Verizon and Sprint, respectively. The consumer protection group Free Press referred to Eisenach and Jamison as “industry operatives” who have “habitually opposed the communications rights of real people, prioritizing instead the monopoly-minded views of companies like AT&T, Comcast, and Verizon ... ignoring the many people who struggle to pay escalating costs to connect and communicate.” Eisenach didn’t respond to an interview request for this story. Jamison and Layton declined interview requests.

In tech circles, a grim future for net neutrality is treated as a certainty, despite Trump’s silence on the issue. “Trump hates net neutrality,” the tech news site Recode wrote the day after the election. Trump’s picks for FCC leadership are likely “to hand control of the internet back to service providers like Comcast and Verizon,” The Verge reported, citing scuttlebutt in Washington.

Larry Downes, a project director at the Georgetown Center for Business and Public Policy, says advocates’ concerns are overblown—in part because there’s “really is nothing to go on,” to discern what Trump might do. (Trying to predict what the president-elect has planned is like playing “the world’s worst game of poker because every card is wild,” he said.) Downes believes that Trump’s team wants to see the open-web flourish—just not under FCC rule. Legislation is one possible approach, for example, and he’s advocated for that path in the past. A common refrain among those opposed to the rules is that government oversight is likely to delay essential infrastructure upgrades that could be spurred by private competition.

“If you’re trying to read the tea leaves,” Downes told me, “If the insider-D.C. folks that are on the transition team—and certainly the current Republicans on the FCC board—if they’re the ones setting the agenda, then I would say zero-rating is something that will not be forbidden or prohibited.”

“Other than that,” he added, “Who knows.”

An example of a zero-rating service that has faced much scrutiny in the United States is T-Mobile’s “Binge On” program, which lets customers bypass data caps in order to watch streaming video on their cell phones. Facebook has been criticized for its zero-rating service, Free Basics, which was effectively banned in India earlier this year.

Business leaders in the U.S. share similar predictions about the future of zero-rating in the States. Charlie Ergen, the chief executive of Dish Network, told The Wall Street Journal that the Trump presidency means “you may see net neutrality be challenged or weakened going forward,” and specifically cited concerns about what that could mean for zero-rating in his industry. Content providers like Dish and Netflix, who aim to keep their own operational costs low, are often in favor of net neutrality rules. Internet service providers—like Comcast and Verizon, which could profit from making companies pay more for faster connections—are often opposed to them.

Layton, one of the member’s of Trump’s FCC transition team, seemed to imply support for predictions about a reversal of the attitude against zero rating. “There is nothing I can say about the future of net neutrality; I can only speak to my research,” she said in an email response to my request for an interview, then shared a link to a paper that outlined findings that “there is no evidence that zero rating harms consumers or competition.”

Trying to predict what will happen by examining Trump’s record is trickier. During his presidential campaign, Trump vowed to block the $84 billion AT&T and Time Warner merger. (Net neutrality advocates consider the merger to be a major threat to the open web—specifically because it would reduce competition and bolster zero-rating.)

“As an example of the power structure I'm fighting, AT&T is buying Time Warner and thus CNN, a deal we will not approve in my administration because it's too much concentration of power in the hands of too few,” Trump said in an speech in October.

But Trump now seems to be walking back that position. After meeting with members of Trump’s transition team, the Financial Times reported that “AT&T executives are confident that their deal has a good chance of passing regulatory scrutiny.” Ergen, speaking to The Wall Street Journal, suggested that there’s an expectation that the Trump administration will be light-handed in its approach to regulation—including its consideration of the AT&T-Time Warner merger—which could then pave the way for more mega-mergers in telecommunications.

All of which means that the debate over net neutrality still isn’t settled—and may become more complicated than ever—under President Trump. “It’s still very early,” Russell Brandom wrote for The Verge last week. “Trump might ignore the FCC entirely, or the agency might focus on unrelated issues. But coming off an unusually active term under chairman Wheeler, it’s clear the wave of aggressive telecom regulation is over.”

The Republican party’s 2016 platform referred to existing net neutrality rules as the “gravest peril” putting “the survival of the internet as we know it ... at risk.”

But Trump is unpredictable enough that looking to his party doesn’t offer much clarity as to what he might actually do. Rather than basing his decisions on overarching principles—or party platforms—the president elect often seems to be guided by vendetta (or at least the desire to generate a punchy sound bite).

Trump’s record of opposing monopolies, for instance, often centers around his disdain for the media, which was a reliable crowd-pleaser among his supporters. Last spring, Trump accused Amazon as having a “huge antitrust problem” and claimed Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, was using his ownership of The Washington Post as a political bargaining chip to avoid scrutiny. (Relatedly, Trump then attempted to ban The Washington Post reporters from covering his campaign events because he didn’t like the newspaper’s coverage of him.)

One final clue as to how Trump might think about net neutrality is by looking at his biggest supporter in Silicon Valley, the billionaire Peter Thiel.

“I don’t like government regulation,” Thiel said when asked about net neutrality in a Reddit forum two years ago. “We need the U.S. government to regulate the internet about as much as we need the EU to regulate Google—I suspect the cons greatly outweigh the pros, especially in practice.”