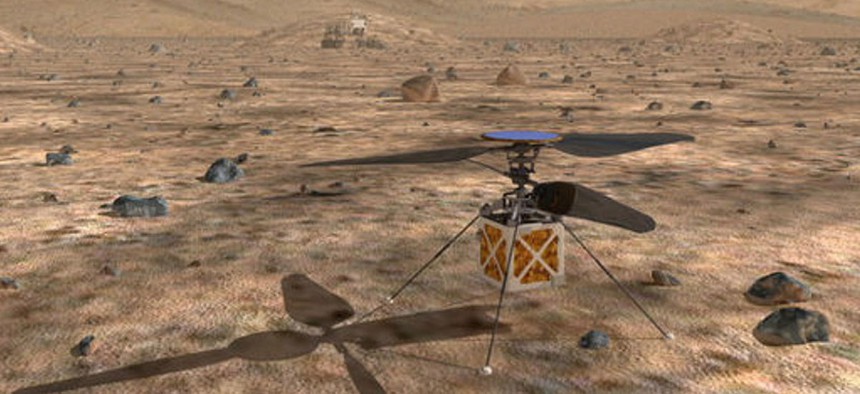

NASA / JPL-Caltech

Helicopters Are Coming to a Planet Near You

... beginning with a tiny chopper that is set to land on Mars in 2021.

The first space missions humans sent to Mars were flybys. Spacecraft had one chance to observe the planet before hurtling away, never to return. Then came the orbiters, designed to be captured by Mars’s gravity and stick around. Eventually, the orbiters started bringing landers with them, dropping them on the rust-colored surface. Then came the rovers, built to move along the rocky terrain. Over decades, these artifacts—some still running, others defunct and coated in dust—have created a kind of museum exhibit on Mars, a timeline of human technology as it matures.

In a few years, NASA hopes to add a new kind of machine to the display.

The space agency announced on Friday it would include a small, autonomous helicopter on its next mission to Mars, which will launch a rover in July 2020 to study the surface for signs of ancient life. The four-pound helicopter, about the size of a softball without its two blades, will be equipped with two cameras. It will receive commands from Earth about where to go and then fly on its own. The Mars helicopter is a 30-day technology demonstration, which means its only job is to work. If the demonstration goes well, it would be a game changer for future exploration of planets and moons in the solar system.

Aerial probes can cover more ground than rovers. At top speed, Mars rovers like Curiosity and Opportunity can only reach about 0.1 miles an hour. Rovers aren’t built to traverse over difficult terrain, and their wheels are prone to damage from sharp rocks. Autonomous, drone-like spacecraft could hop from one spot to another, providing humans with an unprecedented degree of mobility on another planet.

It would also provide them with a better view. The cameras on rovers can produce some very high-resolution photos, but they can only see so far. Aerial spacecraft can scout exploration targets and then gently swoop down to get a closer look.

The concept of a “marscopter” is not new; NASA has been thinking about the possibility of autonomous aircraft on Mars since the beginnings of space exploration. NASA and others have worked on such technology on Earth just as long. But only in the last decade or so has the technology of autonomous aircraft seemed to mature, such that now drones seem like they’re everywhere—they deliver packages, film movies, crash into the White House lawn.

Now that the technology appears ready, it seems like a natural next step for NASA to take one to Mars—and beyond. NASA is currently considering sending a drone to Titan, a moon of Saturn and one of the most exciting candidates for life in the solar system.

As part of a robotic-mission competition, NASA gave $4 million to the team of Elizabeth Turtle, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory, to develop her design for an autonomous dual-quadcopterthat would roam Titan, Saturn’s largest moon.

Dragonfly would spend its mission flitting from location to location, touching down on the surface to study the moon’s chemical composition and search for signs of life. NASA will decide next year whether to pursue this mission or the competition’s other finalist, the Comet Astrobiology Exploration Sample Return (CAESAR), which would study a comet that approaches the sun about every six-and-a-half years. “In just a few flights, Dragonfly will be able to go farther than the Opportunity rover on Mars has in the last 12 years,” Peter Bedini, the program manager for Dragonfly, said at a talk last year.

Titan, like Earth, is an ocean world. Through a process similar to that of our water cycle, methane clouds release methane rains that feed methane seas, lakes, and streams that scientists hope contain some kind of life-forms. Titan is also a great place to fly.

Titan has a thick atmosphere and low gravity, which together provide the perfect conditions for easy flight. If you strapped some makeshift wings on your arms and started flapping on Titan, you’d soar. You’d be unfathomably cold—maximum surface temperatures hover around -292 degrees Fahrenheit—but you’d be flying.

“It’s easier to fly there than it is to fly on Earth,” Turtle says. “In terms of bodies with a solid surface, it’s probably the easiest place to fly.”

It would be easier to fly on Titan than on Mars, which also has low gravity, but a very thin atmosphere instead. The thinner the atmosphere, the more work the helicopter blades must do to generate lift and get off the ground. That’s why the Mars helicopter is so light.

In theory, drones could visit most of the other planets in the solar system. All they need is an atmosphere. But they’d have to face some deadly conditions. On Venus, for example, hardware likely won’t survive the extremely hot temperatures and concentration of sulfuric acid at the surface. It would have to remain aloft, about 30 miles or so above the surface, like the balloons that the Soviet Union sent there in the 1980s.

The same goes for the gas planets—Saturn, Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune—where there’s no ground to land on anyway. The deeper you descend into the atmosphere, the greater the hardware-crushing pressure becomes. Jupiter packs an extra punch, thanks to a magnetic field that gives off dangerous radiation that would zap electronics unless they’re shielded with thick, titanium vaults.

Mars will make a good first candidate for a test helicopter, and perhaps, if NASA picks Turtle’s proposal, Titan will come next. If the thought of an autonomous drone navigating the skies of another planet sounds treacherous, consider that it may be less hazardous than flying one on Earth. At least the Mars copter can’t get stuck in a tree.

NEXT STORY: The Solar System's Icy Secret Keeper