“It hasn’t been good,” Jim Bridenstine, the NASA administrator, recently told me about the work of the contractor, Northrop Grumman. “They know that. Nasa knows that. But we’re gonna get it worked out.”

Nasa has already invested 20 years and billions of dollars in this project. This telescope is going to space. But it’s going to take a lot longer to get there than anyone expected.

Nasa announced on Wednesday the third delay in nine months in the telescope’s launch date. The space agency is now aiming for March 30, 2021. This time last year, NASA officials were still hoping for a fall 2018 launch.

“I’m not happy sitting here having to share this story,” Thomas Zurbuchen, the associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, told reporters on Wednesday. “We never want to do this. We always want to talk about the successes that we have.”

Nasa pushed the launch date after receiving a host of recommendations from an independent review board that was convened after the previous delay—from spring 2019 to spring 2020—was announced in March. The board, chaired by Tom Young, a NASA and industry veteran, found 2020 wasn’t realistic. “When we examined [that target] and when we went through risk and threats and issues that existed ... it was our assessment that still too much optimism had been built into the schedule,” Young told reporters.

The delay means that NASA requires more federal funding to finish testing and assembling Webb. The total lifetime cost of the telescope, which includes development, launch, and five years of operation, will increase from $8.8 billion to $9.66 billion, officials said.

The bigger price tag also means that NASA has breached a cost cap imposed by lawmakers. In 2011, Congress told NASA not to exceed $8 billion in development costs. Officials said they submitted a report declaring this breach to lawmakers this week. Now, if NASA ever wants to get Webb off the ground, the mission has to be reauthorized by Congress.

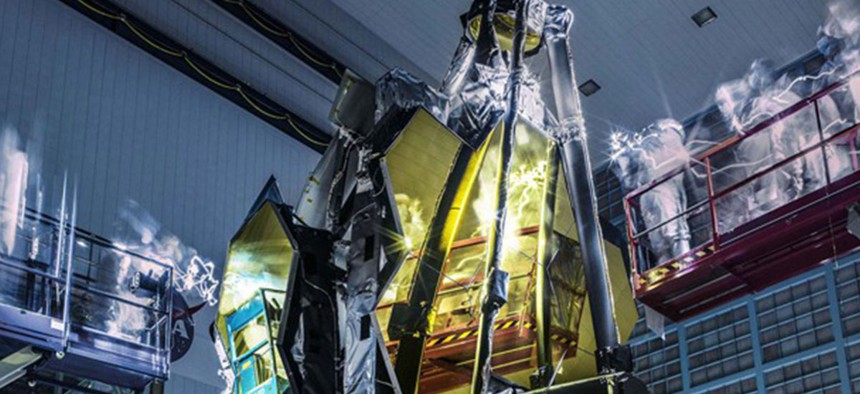

Webb is perhaps the most ambitious astronomy mission in NASA history. It will be 100 times more powerful than the Hubble Space Telescope. With 18 honeycomb-like, gold-plated mirrors, Webb will survey the cosmos in wavelengths the human eye can’t see. And it will be capable of observing pretty much everything, from the earliest stars, galaxies, and black holes that emerged after the Big Bang, to the planets, asteroids, and comets that formed our solar system billions of years later.

“We’re certainly annoyed that we have to wait,” said John Mather, Webb’s senior project scientist, on Wednesday. “We have already decided what to do with the first half-year of observations.” But the wait, he added, will be worth it.

Webb is also unlike anything NASA has attempted to put in space. Its space observatory—the mirrors, a sun shield, and some boxy hardware housing all the systems to make it run—will launch folded up. As it settles into an orbit nearly 1 million miles from Earth, the observatory will slowly unfurl, piece by piece. The automated sequence involves about 180 steps, and Webb can only withstand about six glitches. Anything worse, and Webb will be dead on arrival, condemned to a lifetime as space junk. Unlike Hubble, Webb was not designed to be reachable or repairable by astronauts.

While mistakes were likely expected, some of them contributed to schedule and cost overruns. These were human errors, and they were avoidable, according to Young’s review. They occurred at Northrop Grumman’s facility in Los Angeles, where the contractor is building Webb’s sun shield, a tennis-court-sized stack of layers that will protect the hardware from the sun, as well as the spacecraft “bus,” which will house the observatory’s communication, propulsion, electrical, and other important systems. (The mirrors and science instruments were completed at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland and flown to California in February.)

Young said Wednesday that at one point the wrong solvent was used to clean the observatory’s propulsion valves. The substance turned out to be incompatible with the valves, which workers would have known if they’d called the solvent’s vendor to check, Young said. “This is a mistake that really should not have happened,” he said.

A wiring error caused workers to apply too much voltage to the spacecraft’s pressure transducers, severely damaging them. And during an acoustics test, which examines whether hardware can survive the loud sounds of launch, the fasteners designed to hold the sun shield together came loose. The incident scattered 70 bolts, and engineers scrambled to find them. They’re still looking for a few. “We’re really close to finding every one of the pieces,” Zerbuchen said.

These three errors alone resulted in a schedule delay of about 1.5 years and $600 million, Young said.

Nasa officials said engineers will spend the summer recovering from these mistakes, particularly with the sun shield. They hope to resume testing the various systems in October. When the space observatory is completely assembled, it will undergo still more testing to ensure every bit of hardware is flight-worthy. When it’s ready, Webb will be shipped by boat to a European-operated launch facility in French Guiana.

Nasa officials did not blame Northrup Grumman, but the agency has increased its oversight at the Los Angeles facility in recent months. Nasa has redeployed engineers who had already finished their part on the mission, and even drawn in engineers from the ranks at Goddard who haven’t been involved. “We’re part of this team that has created this problem we’re in,” Zerbuchen said. “Of course Northrup Grumman is part of this, but we have oversight of this, so we take responsibility as well.”

Stephen Jurczyk, NASA’s associate administrator, said the agency gives Northrup Grumman “performance plans” every six months, evaluates them based on those expectations, and pays them based on the outcomes. “Their award fees have reflected their performance in the previous period, and they’ll reflect performance moving forward,” Jurczyk said. “That’s how we hold them accountable and reward them for good performance—and not, for not-so-good performance.”

The current situation ranks high on NASA’s list of nightmare scenarios for this telescope, just under an explosion on launch day. When Webb was first proposed in 1996, officials estimated the mission would cost between $1 billion and $3.5 billion. More than a decade later, predicted costs had ballooned. In 2010, Nature called Webb “the telescope that ate astronomy.” As Webb consumed more and more funds, other NASA projects stalled. (When that article ran, NASA’s launch date was 2014.)

Bridenstine, Young, and Wes Bush, the CEO of Northrop Grumman, will face lawmakers at a hearing of the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee next month, and they should expect some heavy scrutiny. Lamar Smith, the Republican committee chairman, is well-known for being an astronomy fan, but it seems like his patience with Webb is wearing thin. “Program delays and cost overruns don’t just delay the JWST’s critical work, but they also harm other valuable NASA missions, which may be delayed, defunded, or discarded entirely,” Smith said in a statement Wednesday. Smith’s Democratic counterpart on the committee, Eddie Bernice Johnson, expressed similar concerns. “I hope and expect that NASA and Northrop Grumman will take the [review’s] recommendations to heart so that Congress can have confidence that the taxpayer dollars invested in this project are not wasted or adversely impact the rest of NASA’s science programs,” she said in a statement.

Zerbuchen said it’s too early to tell what kind of support Webb’s reauthorization will receive on Capitol Hill. Bridenstine told me he would lobby for the mission. “When I testify to Congress, I’m going to encourage them to be committed to this mission,” he said. “We’ve gone a very long way now. And at this point, the science that we’re going to get back from the James Webb is sufficiently important that we need to finish the project.”

In the next three years, there will be no room for error—quite literally. Young said the new schedule makes no allowances for any additional, time-consuming mistakes.

Even in space exploration, too much of a good thing can set you back. Young cited “excessive optimism” as one of the reasons for the cost and schedule overflows.

On Wednesday, a reporter asked Zerbuchen whether NASA had bitten off more than it could chew. “We want to take leaps, otherwise we’re not NASA,” Zerbuchen replied. “But how big a bite should we take is really something that we’re asking across the board and really are trying to learn how to do it the right way. That’s something that we’re spending a lot of time thinking about.”