The wave of mission hiccups began in June, with a massive storm on Mars. The planet’s thin atmosphere swelled with dust and blocked sunlight from reaching the surface. In the darkness, the solar-powered Opportunity rover could no longer charge its batteries, so it went to sleep. The skies cleared in September, and engineers hoped that the return of sunshine would prompt Opportunity to wake up. But they still haven’t heard from the rover, and NASA leadership has already thought about when the team may have to give up on it.

The Kepler Space Telescope was next. Since its launch in 2009, Kepler has discovered thousands of planets beyond the solar system, including 30 Earth-sized planets that orbit in their stars’ habitable zones, where liquid water, a precursor to life, can exist. Kepler was expected to run out of fuel sometime this year and lose the ability to orient itself, but engineers didn’t know exactly when. The spacecraft’s design didn’t call for a gas gauge, which some scientists have privately said would probably have been a good idea, in retrospect.

In July, Kepler started showing signs of running very low on fuel, and the observatory has been in and out of safe mode since. The telescope emerged from slumber in August, observed the skies for about a month, and then went under again in October. On Friday, NASA announced that engineers had awakened Kepler once more. They will now download the telescope’s latest data while trying to use as little fuel as possible.

In mid-September, another Mars rover went to sleep. Engineers discovered a technical problem on Curiosity’s main computer that prevented it from beaming home the science and engineering data stored in its memory. They turned off the robot’s scientific instruments just in case, and last week switched it over to a backup computer. Nearly a month later, they’re still investigating the glitch.

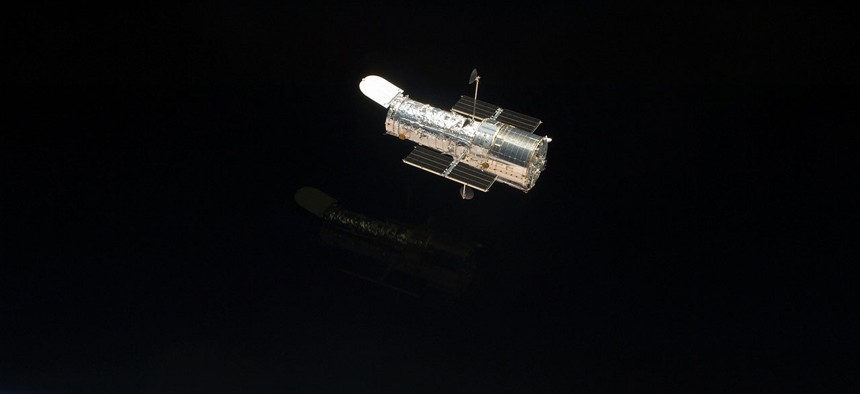

Then, this week, a mere four days after NASA revealed it had shifted Hubble into safe mode, the space agency announced that a different space observatory had put itself into the same state: the Chandra X-ray Observatory. Chandra is designed to detect emissions of X-rays, a form of electromagnetic radiation, from extreme spots in the universe, like exploded stars, galaxy clusters, and the tumultuous environments around black holes. NASA said Friday it doesn’t know why Chandra entered safe mode, and an investigation is underway. They suspect a gyroscope may be involved.

NASA spacecraft, from space telescopes to planetary rovers, are hardy things. Missions almost always outlive their predicted lifespans, and the engineers behind them often find creative ways to overcome technical difficulties.

Chandra, the X-ray mission, was designed to last five years; it marked its 19th anniversary this summer. Hubble recovered from a disastrous mirror glitch in the 1990s that produced blurry images. The Opportunity rover was expected to last 90 days, but made it to more than 14 years. Its companion rover, Spirit, suffered a broken front wheel two years into its mission and spent the next four driving backward in order to get around before it stopped functioning in 2010.

Three years into the Kepler mission, two of the observatory’s four reaction wheels, the devices that allowed it to maneuver in space, failed. Engineers couldn’t repair them, but they did come up with a clever way to keep Kepler going: When the light of the sun pressed against the space observatory’s solar panels, engineers programmed the two remaining wheels to press back. That interaction allowed them to point Kepler where they wanted.

The spacecraft’s extended careers have provided scientists and engineers with more data than they ever expected. It has also given them more time to grow attached to the spacecraft, to view them as extensions of humanity rather than a tangle of wires, to anthropomorphize them. These connections make saying goodbye, whenever the time comes, that much harder.