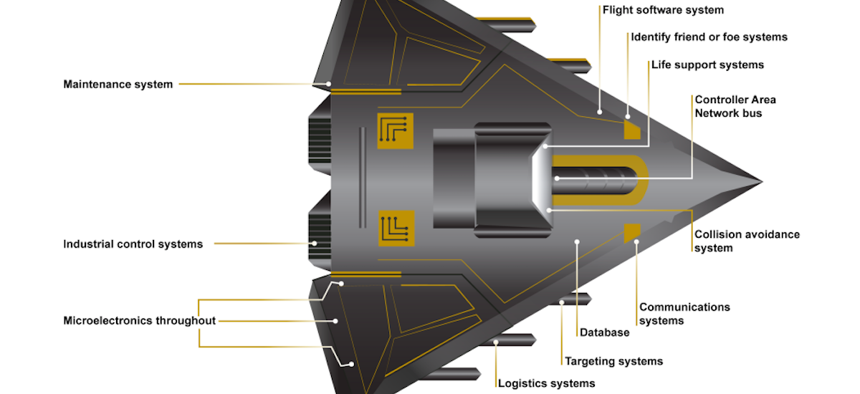

Embedded Software and Information Technology Systems Are Pervasive in Weapon Systems (Represented via Fictitious Weapon System for Classification Reasons) GAO

Many of the U.S. Military’s Newest Weapons Have Major Cyber Vulnerabilities: GAO

Testers achieved access with simple tools, default passwords, and long lists of known-yet-unfixed vulnerabilities.

Many U.S. weapons have “mission-critical cyber vulnerabilities,” including some currently under development and some whose flaws were first identified years ago, according to a new report from the Government Accountability Office, or GAO.

In an investigation that began in July 2017 and concluded this month, GAO testers discovered some shocking security problems. In many cases, the weapons and systems still used default passwords. In others, unauthorized access could be obtained with “relatively simple tools”; in one case, it took nine seconds.

The testers also looked for previously reported vulnerabilities. In one instance, only one in 20 had been fixed.

The problems that the testers found weren’t small ones. In some cases, scanning the weapon caused it to shut down. In another, the test had to be halted for safety concerns.

It's not the first time monitors and observers have sounded the alarm on cyber-vulnerabilities in weapons. GAO first warned of such issues in 1991; five years later, an agency report said “that attackers had seized control of entire defense systems, many of which support critical functions, such as weapons systems, and that the potential for catastrophic damage was great.”

But the problem appears to be getting worse. As weapons become complicated and interconnected with other arms, radios, and platforms, they are becoming more vulnerable.

“More weapon components can now be attacked using cyber capabilities. Furthermore, networks can be used as a pathway to attack other systems,” the new report warns. “We and others have warned of these risks for decades. Nevertheless, until recently, DOD did not prioritize cybersecurity in weapon systems acquisitions.”

In 2015, then-NSA Director Adm. Mike Rogers told the Senate Armed Services Committee that bad assumptions and sanguine optimism about interconnectivity had led Pentagon planners to judge that the benefits of connecting weapons outweighed the risks.

“We are trying to overcome decades of a thought process…where we assumed that the development of our weapon systems that external interfaces, if you will, with the outside world were not something to be overly concerned with,” Rogers said. “They represented an opportunity for us to remotely monitor activity, to generate data as to how aircraft, for example, or ships’ hulls were doing in different sea states around the world. [These are] all positives if you’re trying to develop the next generation of cruiser [or] destroyer for the Navy...That’s where we find ourselves now. So one of the things I try to remind people is: it took us decades to get here. We are not going to fix this set of problems in a few years.”

Even so, the Pentagon is moving quickly toward a new operational construct to better connect virtually every ship, jet, drone, and soldier on the battlefield in a data-sharing web.

Last year, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Goldfein laid out his plans for an Air Force where every device, pilot, and platform does a lot more digital sharing. “What would the world look like if we connected what we have in that way? If we looked at the world through a lens of a network as opposed to individual platforms, electronic jamming shared immediately, avoided automatically?…Platforms are nodes in a network,” Goldfein told airmen at the Air Force Association conference in September 2017. Other service chiefs have echoed his view, effectively revealing—at least in part—the Pentagon’s grand plan for dominance across the domains of air, sea, land, space, and cyber, a strategy that appears in conflict with cyber best practices.

The new GAO report makes no recommendations for fixing the problem. It does cite a 2015 RAND study that looked specifically at the Air Force and recommended: “Close feedback gaps and increase visibility of cybersecurity by producing a regular, continuous assessment summarizing the state of cybersecurity for every program in the Air Force and hold program managers accountable for a response to issues.”

In theory, moving toward a secure cloud environment—one that would allow better and ubiquitous monitoring of data and tracking of anomalies at the hypervisor level—would enable faster detection of intrusions and increase safety. That’s the promise of cloud computing for security, its proponents say. That could allow the Pentagon to realize its goals of better connecting everything without compromising security.

The GAO report suggests that the Pentagon has a long way to go in achieving that balance.