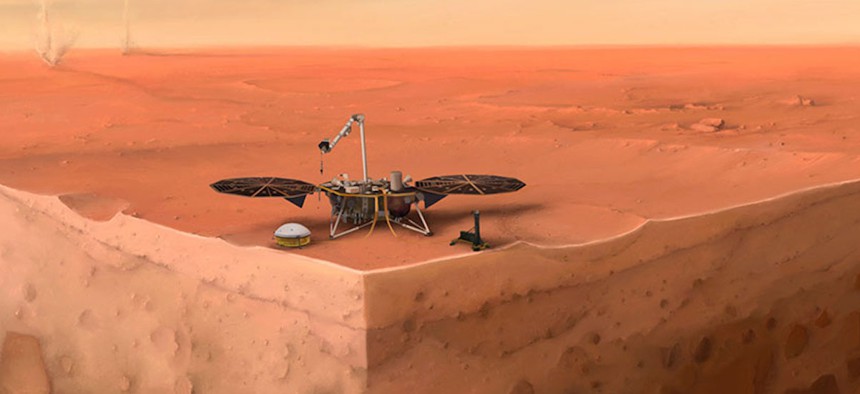

In this artist's concept of NASA's InSight lander on Mars, layers of the planet's subsurface can be seen below, and dust devils can be seen in the background. IPGP/Nicolas Sarter

The Simple Task That Mars Made Impossible

NASA spent nearly two years trying to wrangle a probe designed to burrow into the planet’s soil.

Troy Hudson didn’t want to think about Mars. It was Christmas, he had taken some time off, and this planet had enough going on at the end of 2020. But Mars was difficult to escape, he told me. It twirled in a mobile of the solar system in his home. It sat right there on his skin, tattooed on his arm, below the elbow. Hudson had spent more than a decade working on a robot that was currently parked on the surface of Mars, and NASA was about to decide whether to give up on it.

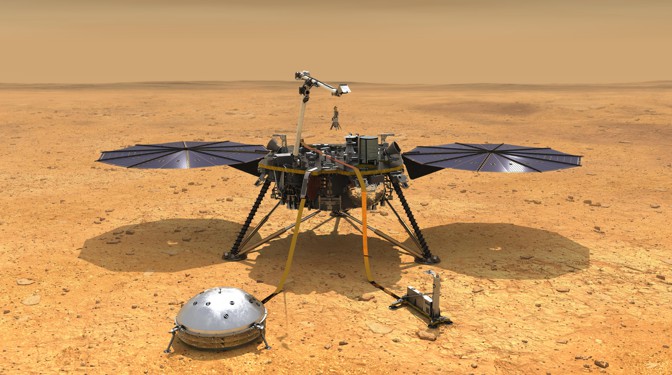

Hudson is an engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where he works on the InSight mission, which delivered a lander to Mars in late 2018. One of the spacecraft’s instruments, a spike-shaped probe called the “mole,” had struggled for nearly two years to hammer into the soil. At several moments during the desperate efforts to rescue the probe, team members believed they could succeed. Of course they thought that—this is NASA, and NASA is known for doing some improbable things, especially with robots. Plus, NASA is good at Mars. For decades, it has sent machines to orbit, drive, and drill around the planet.

The mole was supposed to burrow deeper on Mars than any other machine in history, to measure the heat flowing from within the planet, like an interplanetary thermostat. But the team could never get it to work. By the time the holidays arrived last year, commands for one final effort in January were programmed and beamed toward Mars. There was little Hudson and his colleagues could do but wait.

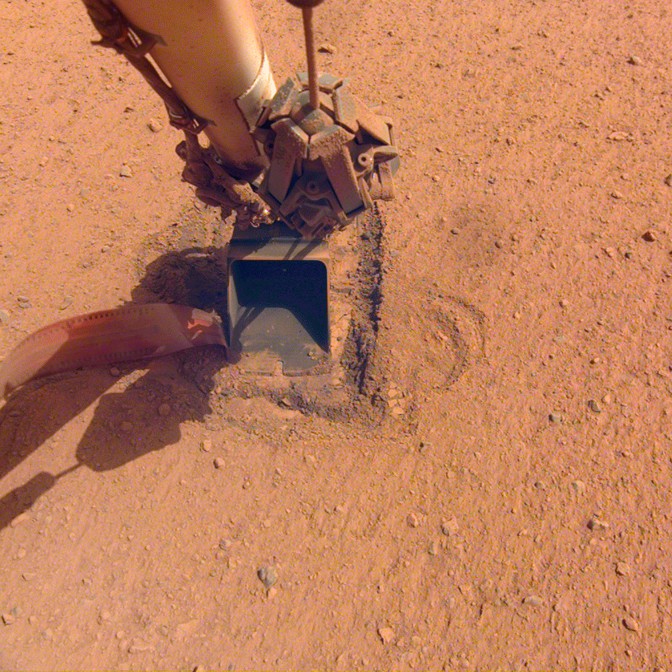

The mole began hammering into the soil earlier this month, but it didn’t make much progress. When the mission left Earth, the team had anticipated that the tip of the probe would reach a depth of about 16 feet (5 meters) below the ground. Scientists now believe it has reached only about 16 inches (40 centimeters). NASA has decided to call it: Insight's overall mission will continue, but the mole’s work is over.

“It’s a huge disappointment,” Sue Smrekar, the deputy principal investigator of the InSight mission at JPL, told me. Sometimes, a Mars mission is a triumphant success, a wonder that shows the people back home a glimpse of a world they can’t experience for themselves, and brings the species a little closer to understanding its own story on this planet. Other times, it’s closer to a Roomba stuck in a corner of a living room millions of miles away.

Mars used to be like our own planet back in the day, a few billion years ago. It was wrapped in a thick atmosphere. It had lakes and rivers of flowing water and clouds in the sky. But somewhere along the line, Mars and Earth, rocky worlds forged from the same nebulous cloud of leftover star stuff, diverged. Mars became a cold, barren world. Earth clung to its warm conditions, giving rise to a lush landscape.

The InSight mission and its instruments were designed to investigate Mars’s history and the forces that shape rocky planets. The mole, in particular, was meant to hammer itself into the ground, trailed by a tether embedded with sensors. InSight’s landing spot met the usual criteria for Mars missions: smooth, flat, and boring. No one wants their robot to land on a rock and tip over. Geologists pored over observations from orbiting spacecraft and other surface missions and settled on a spot they thought would have soil as fine as grains of sand on a beach—just the kind their new probe needed.

When the probe started hammering in the winter of 2019, the team gathered at JPL headquarters in California to await a message from Mars. It anticipated that the mole would have traveled some distance underground. But the data returned a startling number: zero.

Had the mole hit a rock? Was it damaged? The team commanded the probe to keep trying, checking after each bout of several thousand hammer strokes. The first few months of troubleshooting were frantic, Hudson recalled, “because there were so many possible things that could have been wrong.”

[Read: A glimpse into the Martian past]

It turned out to be the soil itself. The team had expected that as the mole hammered and descended, loose soil would collapse around the probe, providing the friction it needed to keep going. But this soil was sticky, clumping together, and had drawn away from the mole, leaving nothing but space on all sides. “It’s as if you are trying to hammer a nail into a hole in the wall,” explains Tilman Spohn, the principal investigator for the mole experiment at the German Aerospace Center, which provided the tool to NASA. “The nail has no grip.”

Before the InSight mission left for Mars, engineers had tested the mole in a variety of soil types. They noticed that the probe bounced back in some tests with stickier soil, particularly in Mars-like atmospheric conditions. But it worked well in most cases, and the mission was close to launching. There wasn’t enough time to make significant design changes, only small adjustments. “We decided to take our chances, because we believed the probability of success was still high enough,” Hudson said.

After the initial failure, the team tried to cajole the mole into action with a number of unplanned maneuvers. The rover’s robotic arm scooped soil over the mole and even pushed down on the probe. The mission’s seismometer instrument, designed to detect Marsquakes, monitored the rumbling of the mole’s hammering attempts. It was slow, painstaking work. The team rejoiced on the days the mole descended a little deeper, and despaired on the days when it had bounced back. “Every time we would do something on Mars, you were on pins and needles to see—does it work? How did it go?” Khaled Ali, a JPL engineer who works on the robotic arm.

[Read: NASA goes looking for tiny ancient Martians]

By last fall, team members had managed to put the mole underground, but they still faced the same problem—the sticky soil—and the robotic arm couldn’t help it any longer. If you could pick up the soil around InSight and “wiggle your hand just a little bit, it [would] probably just break it into pieces," says Nick Warner, a geologist at SUNY Geneseo who helped select the landing site. “It has just the weakest, little bit of cohesion.” But that stickiness was enough to derail the mole’s mission.

Every engineer and scientist I spoke with about this mission spun it as a partial success. Thanks to the mole, they have made unanticipated discoveries about the landscape of an alien world. Better to learn something new than nothing at all. Warner and other scientists believe that the soil contains some salts that are behaving like cement; they’ve seen this kind of regolith on Mars before, but they didn’t expect to find it here, and anyway, no one had tried to burrow into it. Engineers knew the mole’s mission was risky. Predicting the conditions you might encounter on another world is hard—and managing them when they wreck your predictions is harder still.

Although NASA has said goodbye to the mole, the agency has extended the InSight mission until the end of 2022, recording the vibrations coming from deep within the red planet. A new NASA mission arrives in just a few weeks, a rover named Perseverance. Despite the lovely image of one spacecraft coming to assist another, Perseverance is not a rescue mission, and it won’t land anywhere near InSight. The rover’s task will be to search for potential signs of fossilized life in the soil, using drill technology that has already been tested on the planet.

This article was originally published in The Atlantic. Sign up for their newsletter.