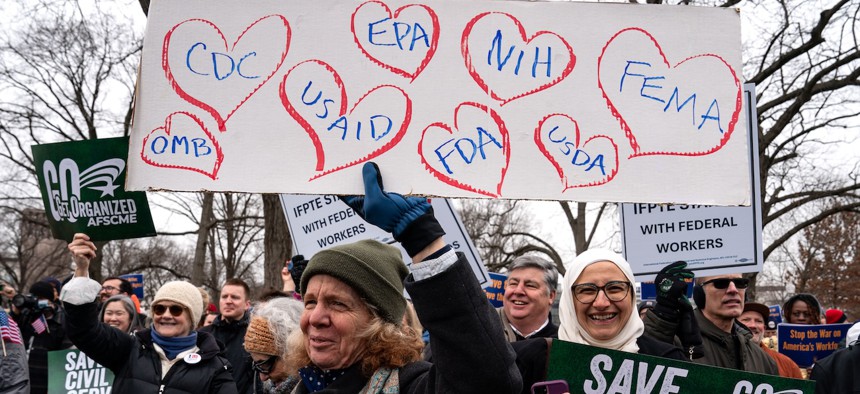

People gather for a "Save the Civil Service" rally hosted by the American Federation of Government Employees outside the U.S. Capitol on Feb. 11, 2025. Kent Nishimura/Getty Images

The DOGE risk to fighting waste

COMMENTARY | We all want to get rid of waste, fraud, abuse and mismanagement in the federal government, but this is not the way to do it, argues one observer.

There are at least two things that everyone around the country agrees on: there’s waste, fraud, and abuse in the federal government—and that we ought to do everything we can to root it out.

And in rooting it out, there are two more things we can agree on. The war on unholy “waste, fraud, abuse” trio has been around for a very long time. Ronald Reagan, after all, launched his own proto-DOGE in 1982 with the goal of “improving management and reducing costs.” Second, there’s always been a mysticism around this trinity, which assumes it could be made to disappear like a lion in a Las Vegas show, by waiving a magic wand.

Ahh, if only it were that easy.

In fact, as the Government Accountability Office makes clear in its new high-risk report on federal programs most prone to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, we certainly could save billions of dollars. Past work on GAO’s checklist has saved $759 billion, with $84 billion recouped in just the last two years. There are billions more we could take back.

That’s what the Trump administration wants. It’s the job that DOGE has. It’s the key to reassuring taxpayers that their hard-earned tax money isn’t going to waste. But what DOGE is doing is precisely the wrong way to get there.

GAO’s new report lays out the facts in the 323 pages of its new report. Cutting waste, fraud, abuse, and mismanagement requires three “C’s”—coordination (mentioned 33 times in the report), capacity (at 68 times), and capital (human capital, that is, with 27 mentions).

Look at coordination. GAO added federal disaster assistance in this edition of the biennial report it’s been producing since 1990. In the last year, the federal government spent more than $1 billion in helping communities recover from the economic damage they suffered. But it’s tough work for the lead agency, FEMA, with its people pulled in so many directions at once, from the Franklin Fire in California to wildfires in North Dakota to Tropical Storm Ernesto in Puerto Rico. Vastly complicating FEMA’s job is the huge number of federal agencies with a hand in disaster recovery—30 in all.

Project 2025 has an answer to the problem: sending “the majority of preparedness and response costs to states,” as well as “eliminating most of DHS’s [Department of Homeland Security, which houses FEMA] grant programs.” No state, however, has pockets deep enough to fund the response when disasters strike, and no state has enough surge capacity to get the help that’s needed to the place it’s needed at the time when it’s needed. Even California called for outside aid in the midst of January’s wildfires.

So, if we’re to help people in their worst moments and save taxpayers’ money, we need to do a far better job of connecting the big federal players—FEMA, HUD, and the Transportation Department—to prevent costly duplication, on one hand, and cracks in the system through which people can slide, on the other. Then the federal system needs to connect far better with state and local agencies. If there’s anything we’ve learned about disaster response, from the recent crash of the American Airlines jet into the Potomac to Hurricane Helene in North Carolina, those connections depend on building, in advance, the relationships of trust that shape an effective response.

In short, cracking this problem requires better coordination.

Then look at capacity. Cost cutters salivate at getting their hands on improper payments in Medicare (which GAO estimates at $54.3 billion in 2024) and Medicaid (at least $31 billion). Some of this $85 billion is legitimate but isn’t backed up because of sloppy recordkeeping. Some of it is undoubtedly fraud. No one knows for sure how much fraud there is, especially because private contractors do the front-line work in managing both programs. And, of course, no one knows how much these estimates might miss (and the people committing the fraud aren’t going to tell anyone).

Running these programs, which amount to about one-fourth of all federal spending, is a tiny bureaucracy, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. It has about 6,000 employees, or 0.3% of all federal employees. For a sense of scale, compare that with the University of Montana. It has about the same number of employees, and they’re in charge of 10,800 students. Medicare enrolls 66 million Americans; for Medicaid, it’s 72 million.

What capacity does the federal government need to recoup tens of billions of fraud in programs covering these tens of billions of Americans? In Medicaid, slashing away at fraud requires strong agency leadership; CMS collaboration with states and contractors to root out problems in managed care programs, which too often feed the fraud; and better monitoring, especially to rake back money that shouldn’t have been paid out.

As a new report from the IBM Center for the Business of Government shows, this means beefing up IT systems, improving AI, and investing in government employees who know how to use these tools. It requires better capacity.

Finally, let’s look at capital—human capital, that is. GAO put 37 areas on its high-risk list. Of these, 20 struggle with a big gap between the skills needed to make the programs work better and the skills government agencies have. This problem has been on the high-risk list since 2001, and there’s no escaping the other problems on the list without first solving this one.

The list of areas where the government’s talents fall short is a long one. It doesn’t have the AI and IT experts it needs. It needs more employees with strong skills in project management, organizational performance, leadership development, and data analytics. But not only has the government’s human resourcesagency, the Office of Personnel Management, “not yet developed an action plan,” GAO explains. It has failed even to figure out which skills it most needs, where it needs them, or how to get them.

And now, in the last month, the wholesale assault on government workers has made things worse. This strategy was crafted to drive away existing workers and to discourage new employees from joining the government. For anyone trying to slash waste, fraud, and abuse, however, this is remarkably counterproductive. The entire federal payroll in 2024, counting salaries and benefits, was $337 billion. Cutting, say, one-fourth of that would save $84 billion. But it would put at grave risk the federal government’s ability to recoup the tens of billions of dollars that GAO has demonstrated that the government has saved in recent years.

Cuts of that size would even further undermine the federal government’s human capital, which already has big holes. It would weaken government’s capacity to roll out the big new AI and IT systems it needs to go after waste. And it would erode the coordination—with each other, with state and local government officials, and with private contractors—that the government’s employees have steadily developed over the years.

GAO has documented how we can make big improvements in government’s services while increasing service to taxpayers. The new report also has a game plan for reducing fraud, waste, and abuse through strategies that would far more than pay for themselves.

That’s why DOGE is the highest-risk area of all, because it puts in danger the progress that the government has made in reducing fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement—and it opens the door wide to even more.