A health care worker use a nasal swab to test a patient for COVID-19 at a pop up testing site at the Koinonia Worship Center and Village in July 2020 in Pembroke Park, Florida. Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Most of the COVID-19 Workforce Were Women of Color. What Happens Now as Those Jobs End?

Women of color took on the majority of new jobs created during the pandemic to do contact tracing, and to test and vaccinate Americans, experts said. But as sites ramp down, the future of that workforce is now uncertain.

Since 2020, thousands of workers have done the difficult work of meeting people where they are — their car doors, front doors, community centers — to test, vaccinate and contact trace. They often did this work to stop the spread of COVID-19 in their own communities, among their neighbors and families.

They worked in the heat and humidity, under tents in the rain, in clinics and from their own homes, through an onslaught of questions, despair and, sometimes, outright nastiness. Some had a background in public health, some came out of retirement to help, others had never worked in health care at all.

While data on who these workers were is still being collected, one clear pattern has emerged, experts say: It’s likely most of the COVID-19 workforce were women of color.

Historically, the majority of the public health workforce has been women. They are about 92 percent of medical assistants, 90 percent of nurses and medical record technicians, 87 percent of nursing and home health aides, 78 percent of health practitioner support techs, and 74 percent of medical and clinical lab techs, according to 2015 data from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, the most recent available.

Higher pay for those jobs helped buffer some of the losses women in the workforce experienced during the pandemic. But as testing and vaccination sites begin to ramp down, public health experts are looking at a new imperative: how to shore up a field that was already understaffed and now is dealing with burnout by retaining the woman-heavy COVID-19 workforce.

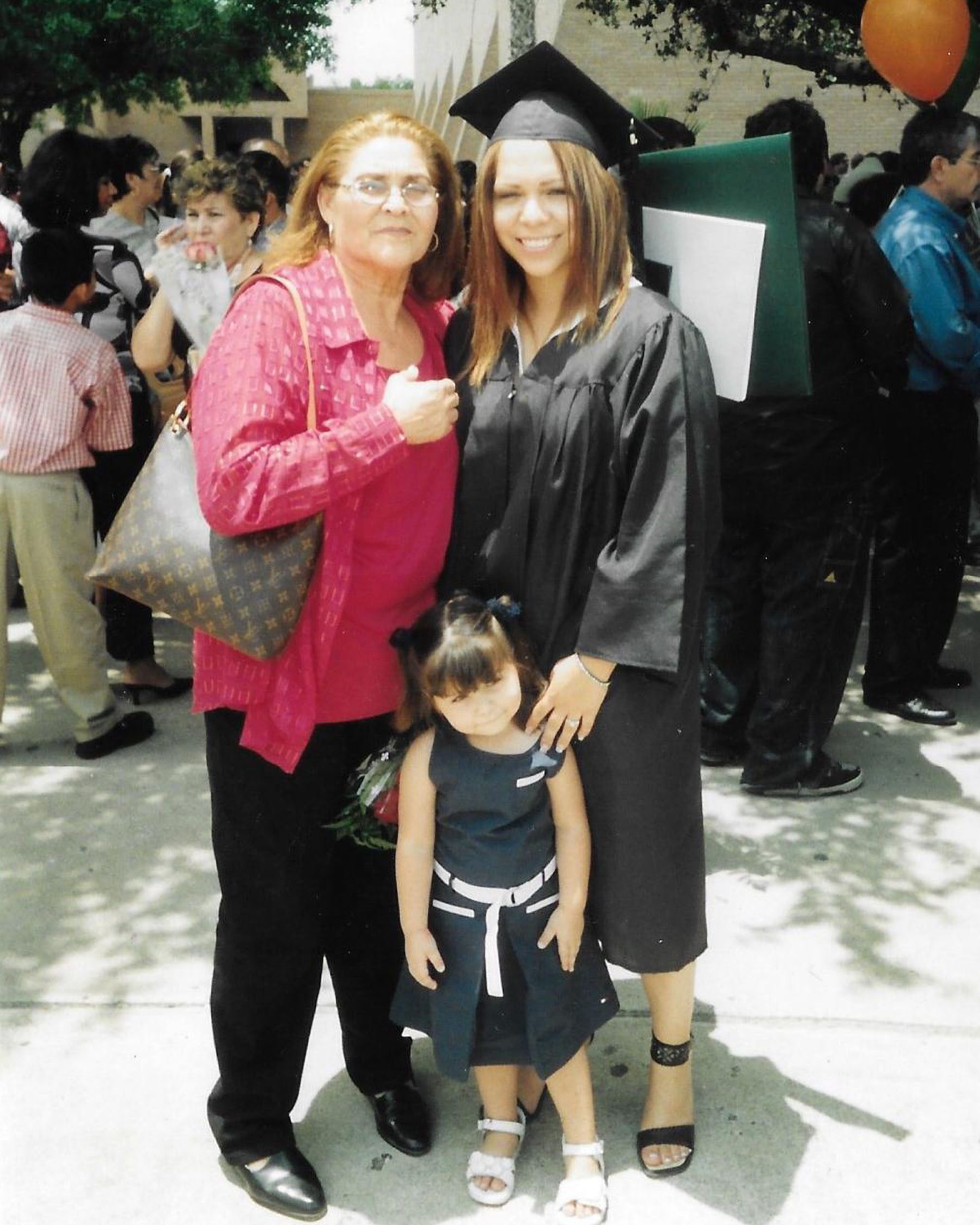

Fresh out of college with a public health degree, Jacqueline Ochoa went to work last year vaccinating vulnerable populations across Houston, many of them uninsured and immigrant communities who had limited access to resources. Ochoa grew up in McAllen, Texas, a border town in the Rio Grande Valley. Raised by her grandmother and mother, a nurse who started out working in shelters for immigrants, her background is similar to many of the people she came to serve during the pandemic: low-wage, relying on food stamps and donations.

She took on a contract job with the San José Clinic, a safety net clinic that provides health services for uninsured people in Houston. She was put in charge of finding communities that had little access to the COVID-19 vaccine.

It was work that often took her to Spanish-speaking neighborhoods around town, places where people couldn’t even afford the time off work to get the vaccine. It took her to immigrant hubs, like an apartment complex for Afghan refugees in west Houston, where one night in the fall of 2021, a family welcomed her into their home. Two parents and five children were living in a cramped 600-square-foot apartment, having settled in Houston after escaping the Taliban and spending time in a refugee camp. Still getting their bearings, they were thankful when Ochoa arrived to administer their vaccines.

That was the kind of work that has marked her time as a part of the COVID-19 workforce, cushioning the many days when doors were shut in her face.

“Some days I’m really tired … but then I have days like this, where I’m like, ‘Wow, you’re actually doing work that matters.’ It’s every kid’s dream when they get out of college, they always say, ‘I want to do a job that actually matters — make a difference in the world.’ I’m actually doing it,” said Ochoa, 20.

Ochoa works with a staff that is almost entirely women of color, and she credits her background as the reason she has been able to reach people who otherwise may not have been vaccinated at all, helping push forward an effort that started to stall by mid-2021.

“To me as a Hispanic woman, I love seeing people of my color and people of my ethnicity doing work that matters,” Ochoa said. “You want to be able to connect with a person who is giving you health care.”

Joanne Pearsol, the director of workforce development at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, said data on the COVID-19 workforce will probably come later this summer, but she expects most of it to reflect the existing trends in public health.

“Public health has been a female-heavy field, I would suspect would remain true during COVID — that’s what I saw,” she said.

Still, the workforce will probably remain difficult to capture — cities, counties, states and organizations have different ways of measuring who was doing that work, and so it’s possible it will never be clear exactly how many people signed on to be part of the pandemic response force.

But their faces were ubiquitous at testing and vaccination sites. In almost every state, it was health care workers who were women of color, most of them nurses, who first got the COVID-19 vaccine. And across the country, women of color created pop-up clinics and led communities as vaccine ambassadors.

Kimberlyn Clarkson, the chief advancement officer at the San José Clinic, where Ochoa works, said the clinic purposefully staffs people of color who are bilingual and culturally competent to work on the vaccination effort because its success hinged on creating relationships with communities. In almost every case that was women.

“We are having to take a lot of really introspective looks at ourselves and wanting to hire people that look like the patients so that we garner the trust,” Clarkson said.

In Philadelphia, people experiencing homelessness were hired as vaccine ambassadors for precisely that reason. The city’s Office of Homeless Services hired seven people experiencing homelessness — five of whom were women — earlier this year to help educate others about the COVID-19 vaccine. They were paid $15 an hour and given a weekly stipend and transportation pass and tasked with talking to people outside of shelters and at clinics, many of them people they knew well.

“We can cite statistics, we can cite facts, we can provide handouts, but there’s also a mistrust of systems and a mistrust of health care, especially for people of color,” said Keisha Moore-Johnson, the shelter services administrator for the Office of Homeless Services and the person who runs the ambassador program. “And so when you have someone that looks like you, that has the same shared experience as you do, it’s just that more impactful in terms of getting the message across and changing that person’s mind.”

Some people who decided to get vaccinated as a result later applied to become vaccine ambassadors, she said. Those who participated in the work, many of them mothers, did so out of a feeling of individual responsibility to their families and their community.

“It was personal for them. They experienced family members getting COVID, some even passed away from COVID, and so they wanted to give back in that sense and share the message on the importance of getting vaccinated,” Moore-Johnson said.

It’s the dual pandemic communities of color endured: Black, Latinx and Indigenous people were about two times more likely than White people to die from COVID-19, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Women of color, who outnumber men in frontline jobs as nurses and health aides, were also more likely to work trying to save others from the virus.

At the Oregon Public Health Institute, Executive Director Emily Henke said her contact tracing program wanted to hire a staff that was representative not of the population of the state, but the population most impacted by COVID-19. The initial goal was to hire a staff that was 33 percent bilingual to do contact tracing. Henke ultimately hired a staff that was 90 percent bilingual, almost all of them women of color. Many had no experience in public health at all. Some were former hospitality industry workers — more than half of the hospitality workforce is women — who were laid off at the start of the pandemic.

“I have no doubt in my mind that our team has saved so many lives, if only because of our early vaccine work around getting medically vulnerable people vaccinated as soon as possible,” Henke said.

The added jobs also helped mitigate some of the economic headwinds of the pandemic. Women suffered the most severe job loss in the early months of COVID-19, with unemployment rates reaching as high as 20 percent for Latinas and nearly 17 percent for Black women, the highest rates of any group according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Well-paying jobs that didn’t require extensive prior experience were in short supply, and for many, the COVID-19 jobs were an opportunity to return to the workforce.

Directors at multiple public health organizations The 19th spoke to said their contracted COVID-19 staff was often earning more than their regular staff in an attempt to attract and retain workers. Henke’s COVID-19 staff started around $22 an hour, $27 for those who were bilingual. Ochoa in Houston earned more than $30 an hour. Directors said it was common to hear of comparable workers across the nation earning $30 or more an hour.

Those opportunities have been bright spots in a punishing couple of years for the health care workforce. Women are leaving health care in higher numbers, especially those on the frontlines of the pandemic and those in lower-paid health care jobs. The COVID-19 public health jobs may now attract new workers to the field as others exit.

Henke said the pandemic did create an opportunity to train hundreds of public health workers who otherwise may not have gone into the field. Many who she employed have gone to pursue an education in the field, she said. Some have moved on to other similar positions.

But for many, the question is now what comes next. Most of the COVID-19 workforce was hired through contracts that were extended as the pandemic continued. But across the country, states are closing mass testing and vaccination sites in response to diminishing COVID-19 case numbers, and the workforce that staffed those positions will have to move on, too.

“We’ve been reducing our staff over the last several months as health departments have changed the way that they respond. Not only have cases have declined, and cases have stopped being reported, and so the calculus around the value of case investigation has changed as well,” Henke said.

In Oregon, Ivett Altamirano is considering where she will go next. She started out doing contact tracing work from home in the summer of 2020 through a six-month contract with the Oregon Public Health Institute. At the time, she was calling as many as 40 to 60 people a day to do contact tracing. Many of those calls were with Latinx people from her own community.

The work was emotionally taxing, she said. Some of the people she called opened up, telling her they had no paid time off to stop working even though they had been exposed to the virus. How would they pay their rent and feed their families?

“It was a lot of the minority communities that were asking for resources or help with rent because those are the same people that, in their job, they did not qualify for any sort of benefits, many of them didn’t have health insurance. They worked either one or two jobs to be able to survive,” said Altamirano, 24.

Her six-month contract was extended several times, and she eventually went to work taking in patients at a physical vaccination clinic. It was fast-paced work that involved managing one difficult situation after another, including hecklers who would question her outside the clinic.

“At first it didn’t really hit me that I went from helping people from getting sick and now helping people from dying or getting a vaccine to prevent a death,” Altamirano said. “After a couple months, I realized I switched over to doing something a lot, in a way, bigger — it felt gratifying.”

Her contract is ending this summer, and she doesn’t know if it’ll be extended again. She has signed up to study public health at a local community college, but she isn’t sure if she wants to work directly with patients again.

For the organizations that staffed workers these past few years, it’s critical to try to retain them in the public health sector. Even prior to the pandemic, the public health workforce was expected to be short more than 250,000 workers by 2020, according to a projection by the Association of Schools and Programs in Public Health.

At the Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations, which received federal grants to beef up COVID-19 workforces, Deputy Director Jen Lee said her team is now working to find placement for the workers who will soon see their contracts end as federal funding for community health organizations provided through the coronavirus stimulus packages begins to dry up.

“You don’t go back — it would be a shame to not allow the resources to continue to flow to allow access for these communities. That’s a big question for us,” Lee said.

The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials is also working on longer-term retention plans that offer more flexibility with remote work that could keep people in the field and combat massive burnout that has plagued the health care workforce at large.

A survey of nearly 45,000 employees in state and local government public health departments by the de Beaumont Foundation and ASTHO published in March found that nearly a third of the workforce is considering leaving in the next year — 40 percent said it was because of the pandemic.

As sites start to slow down, the question of managing burnout and retention has also risen to the surface at the San José Clinic, Clarkson said.

“Maybe it’s time for us to spend more time looking at how to make sure health care workers are well and feel cared for, but I think we are all still trying to figure out what that even looks like right now,” she said. “We lost some staff — people who will not return to medicine.”

Including people like Ochoa.

Her contract will end July 31, and public health may not be in her future now. The time she spent on the COVID-19 workforce was foundational in different ways. It gave her purpose and focus and it showed what she wanted to do — and what she didn’t.

Her mom also worked as a nurse in COVID-19 hotspots from the beginning of the pandemic. The two of them gained a deeper understanding of the sacrifice and difficulty involved in what they did. Their relationship flourished.

Ochoa is proud of the work she did during the pandemic, she’s proud of the work her mother did. Her mom, she said “realized that she did what she had to do. She raised me right, I got my job, I’m doing great.”

Now, Ochoa is ready to find her own path, albeit not in medicine.

She is moving to Dallas, where she plans to work at a shelter managing cases for immigrant children. Like her mom once did.

Originally published by The 19th