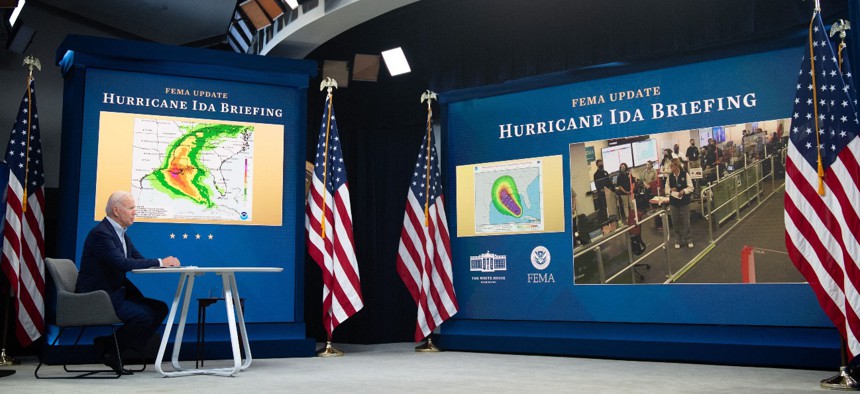

President Biden is virtually briefed by Federal Emergency Management Agency officials on preparations for Hurricane Ida in August 2021. SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images

Deployed FEMA Responders Will Receive New Job Protections Now That Congress Has Passed Much Hailed Reform

Officials say the change will help retain key personnel and avoid staffing crises.

Federal emergency responders who leave their day jobs to address disasters will soon have the same protections as members of the armed forces deployed to active duty, with Congress on Wednesday sending a long sought after reform to President Biden’s desk.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency has beseeched lawmakers to pass legislation like the Civilian Reservist Emergency Workforce (CREW) Act (S. 2293) to help it address critical staffing shortages and a recent wave of departures. Reservists are only paid while deployed to a disaster and the lack of protections they receive for their full-time jobs makes it difficult for the agency to recruit and retain the temporary personnel. FEMA employs more than 12,000 reservists who have been stretched thin due to not only hurricanes and wildfires, but also FEMA's obligations throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It is the heartbeat of what we do for disasters,” FEMA Administrator Deanne Criswell told a House committee earlier this year when asking for the legislation. “It is the majority of our staff that surge in when an incident happens to support local communities.”

The measure would ensure FEMA reservists receive job protections even if they are unable to give notice before deploying to a disaster response. The House passed the bill on Wednesday in a 387-38 vote after the Senate approved it unanimously last year.

“FEMA Reservists serve as an essential part of our federal response to everything from hurricanes, flooding, or wildfires to public health crises,” said Sen. Gary Peters, D-Mich., who introduced the measure. “They should never have to worry about losing their livelihoods when called up to serve.”

FEMA has slowly grown its non-career workforce in recent years, but current and former officials, stakeholders and employees themselves have raised concerns about insufficient resources given current demands. In the 1960s, for example, the United States declared an average of 18 major disasters per year. The emergency response agency responded to 104 such disasters in 2020 and 58 last year. Its capacity to quickly deploy around the country and handle logistics has also led it to take on various other projects in recent administrations, such as helping with an uptick of migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border, the resettling of Afghan evacuees and the COVID-19 pandemic response. Lawmakers and experts have cautioned the increased workload has led to more turnover—and less experience—throughout the agency.

FEMA employees previously sounded the alarm on their lack of down time between deployments, warning of burnout as the agency no longer experiences a true offseason. One FEMA reservist recently told Government Executive new hires were receiving insufficient training—just two-to-three days, virtually—before being sent out to disasters. Some employees were working 12-hour days for a month straight, he said. A former reservist who recently left the agency said she and her colleagues were taken for granted, with few people in the agency looking out for reservists' interests. The lack of protections led many people to leave, she said, and the frontline nature of their jobs caused them to be unfairly scapegoated when things went wrong.

“We have to take the punishment,” the former reservist said.

Lawmakers said their bill would help alleviate some of that pressure.

“This bipartisan legislation will protect FEMA reservists and ensure they do not have to choose between their careers and responding to a disaster,” said Rep. John Katko, R-N.Y.

Criswell told lawmakers in June she is prioritizing the mental health of her workforce and has requested additional funds in the agency’s fiscal 2023 budget to expand those initiatives. She added FEMA officials are in the midst of conducting a comprehensive review of the agency's staffing needs to determine how to better structure the workforce in light of growing demands.