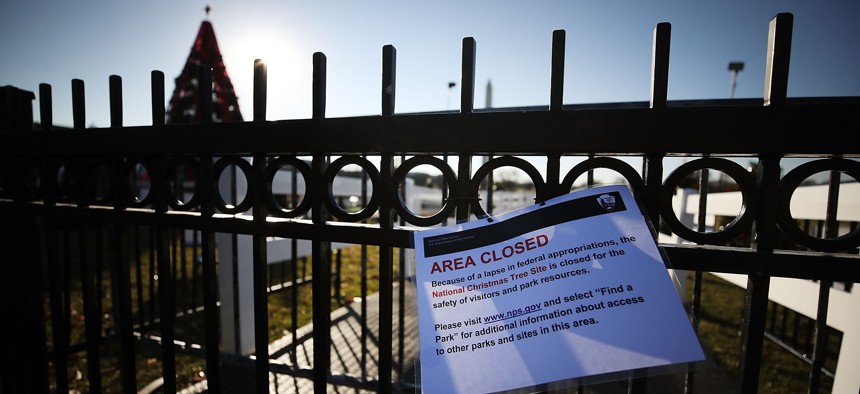

A sign alerted visitors to the the National Christmas Tree that the site was closed to the public due to a government shutdown. Former President Donald Trump presided over a 35-day shutdown between late 2018 and early 2019. Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Shutdowns and the ‘avalanche of work’ for government tech shops

Even if a shutdown doesn’t happen, planning for one has a real cost, former government CIOs say.

It’s not yet clear whether lawmakers will avert a government shutdown by the Sept. 30 funding deadline, but former government IT officials say even the specter of one has an effect on federal tech shops.

Depending on what’s happening on Capitol Hill, processes kick off weeks in advance of potential shutdowns, as agencies plan for a potential lapse in appropriations, sources told Nextgov/FCW.

Richard Spires, former chief information officer at the Department of Homeland Security and IRS, said that even without a real shutdown, planning for one is “a fairly complex undertaking” that “really just throws off your normal, day-to-day work.”

“From a CIO perspective, it’s a lot of work,” confirmed Maria Roat, the former deputy federal CIO from 2020 to 2022 who was CIO at the Small Business Administration during the 2019 shutdown.

There’s planning for which employees need to stay, which contractors can continue working and what communications need to go out, both for employees and the public, said Roat.

In terms of the systems that can continue to operate, agencies have to think about whether they fall under discretionary funding, whether their functions are “excepted” by law or if they are needed to support those functions that are excepted or authorized, a 2021 OMB FAQ states.

Agencies have to put notices on websites that are shut down or operating at reduced functionality to let users know that they might not be up to date and that transactions won’t be processed until the government is funded, according to the FAQ.

Still, “systems are monitored and managed even though there’s a shutdown,” said Roat, noting that cybersecurity can be a big concern. “The threat actors out there… think nobody’s watching.”

OMB emphasizes that cybersecurity operators should indeed be watching. Agencies need to maintain patch management, security operations center and incident response, per the FAQ.

“In making the determination to suspend information technology operations, including websites, agencies must take into consideration cybersecurity risk,” the FAQ states. “Generally, agency cybersecurity functions are excepted as these functions are necessary to avoid imminent threat to federal property. Agencies must also ensure the preservation of agency information.”

Cybersecurity came up as an issue in 2019, Jordan Burris, the chief of staff in the federal CIO office during the 35-day shutdown that stretched across late 2018 and early 2019, told Nextgov/FCW, especially in terms of discrepancies across agencies in how many cyber professionals were kept on board.

“When it came time to respond to a number of incidents, we needed a critical mass of cybersecurity professionals available, and it did create… some delays in getting things moving at a quicker pace,” he said.

Suzette Kent, who was federal CIO during the 2019 shutdown, also said that generally, “some of the agencies looked at who was critical staff a little differently than others,” which also came up in “shared services” that cross agencies.

Overall, “from an IT perspective, almost everyone in IT is considered mission-critical,” she said. “Many of the CIOs were actually in a place where their entire staff was critical or was supporting some component of critical functions,” but “what we were missing was the business and functional partners sometimes that make things work.”

As for the impact, Spires said that the planning process alone has an effect.

“Projects, programs that you’re trying to move forward, a lot of times they get put on hold or very little work really gets done during the time you’re planning for the shutdown,” he said. “So it’s one of those costs that is hard to quantify… but there’s no doubt that there’s a lot of opportunity cost lost when you go through these, even if you don’t shut down, even if you just have to plan for it.”

Real and hidden costs

All that work becomes costly in terms of actual dollars, too, from creating failsafe options, to putting notifications on websites, to missing out on potential cost savings from delayed tech deployments, said Burris.

“There’s a lot of …money that is spent, in being able to orchestrate a shutdown, so actually it ends up costing the government,” said Burris.

“The determination of which services continue during an appropriations lapse is not affected by whether the costs of shutdown exceed the costs of maintaining services,” OMB tells agencies in the FAQ.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated in 2019 that the five week shutdown that year reduced the country’s gross domestic product by $3 billion.

After shutdowns end, there’s often an “avalanche of work” waiting to be done, said Kent. The 2019 shutdown was so long that many feds were locked out of their technology because they weren’t working when required password resets occurred, which led to that “avalanche” for help desks as many feds signed on again for the first time in weeks, she said.

The “ripple effect” can also be felt in delays to tech deployments — often months-long even if a shutdown only lasted a couple weeks — delays to contracts and backlogs for the public, said Roat.

Tech shops also might need to do fixes for problems not addressed during the shutdown, said Burris. There can also be a “retention challenge” after shutdowns. Though furloughed feds are now guaranteed back pay after a shutdown, those paychecks only go through after the shutdown ends.

“A lot of folks don’t like the idea of not having access to their paycheck for a period of time,” he said.

And there are the “human costs” for the people on the other end of government websites and phone lines waiting for services, said Kent.

“During a shutdown, if something goes down and there’s nobody there to fix it, well I guess it stays down, right?” said Roat.

“It's the American people that are impacted the most,” she said. “That's how I see it.”