Mikael Damkier/Shutterstock.com

How to Restore Public Trust in Government, Without Paying a Single Cent

Removing communication barriers is key.

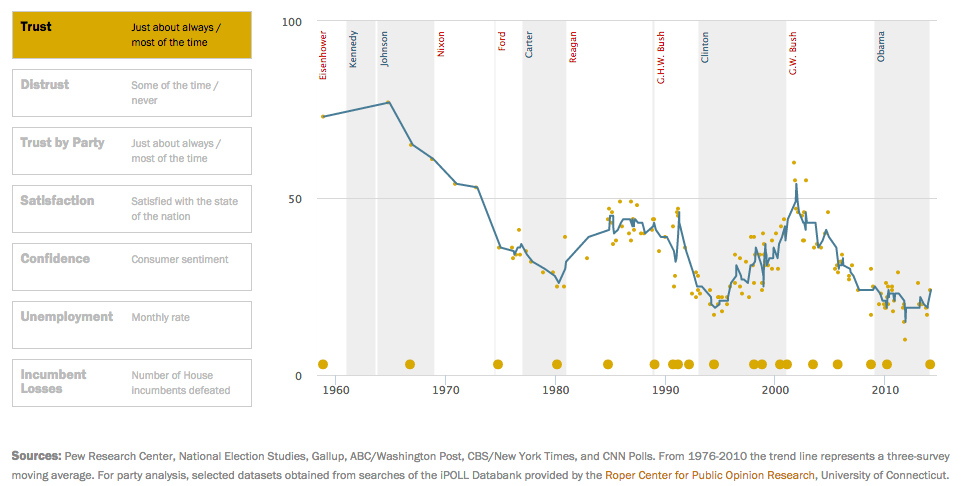

More than three out of four Americans don't trust the federal government. In 2014, only 24 percent of Americans said they trusted the government to do what's right "always or most of the time." Sixty years ago, in 1964, that figure was more than 50 percentage points higher -- 77%. (Source: Pew Research Center, 2014)

Government leaders know that communication is a vital government function.

Recognizing this, nearly 20 years ago, in 1996, Vice President Al Gore formed the Federal Communicators Network.

"The Vice President's vision was to reach federal workers with important reinvention messages, promote a climate in which reinvention can flourish, and create a grass-roots demand to break down agency barriers to reinvention." (Source: National Partnership for Reinventing Government)

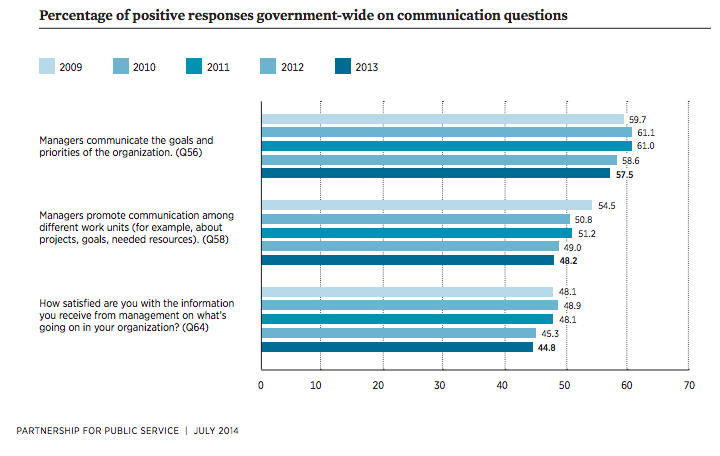

Unfortunately, however, the vice president's vision was not realized. In 2013, only 50.3 percent of the federal workforce was satisfied with the communication they receive from their leaders. They don't feel like they get enough information about:

- Goals and priorities

- News about their agency generally

- Information about what's happening outside their immediate sphere of work

See the table below from the PPS showing the decline in employee satisfaction with leadership communication over just the past few years. For good employee communication to happen, says the PPS, it has to be a priority; it has to take place through a number of channels simultaneously; it has to be open and honest; and employee suggestions have to be taken into account.

The private sector is better than the government at this, says the PPS. And not knowing what's going on obviously leaves people frustrated and unable to contribute fully to the mission.

It goes without saying, but is worth saying anyway:

There is a statistically significant correlation between effective workplace communication and employee job satisfaction, but communicating effectively and motivating employees is a challenge for many leaders. (Deloitte Consulting LLP, “Silencing the Static: Engaging employees in an unsettled environment,” July 2014)

In an environment where internal transparency is scarce, effective external communication is more than challenging. It's impossible.

One might argue that we shouldn't rely on federal communicators: "Let the data speak for itself." But that approach isn't working either. In 2015, 10 out of 12 (83.3 percent) federal agencies most frequently receiving FOIA requests failed to provide adequate access to government information. Again, it's not because federal employees are incompetent. Rather, according to the Center for Effective Government, the function is insufficiently funded, staffed, planned for and automated.

Poor communication and perceived corruption go hand-in-hand.

In 2014, the United States ranked 17 out of 100 on the perceived corruption index published by Transparency International. A score of zero means "highly corrupt," vs. 100 means "very clean." According to TI:

A poor score is likely a sign of widespread bribery, lack of punishment for corruption and public institutions that don’t respond to citizens’ needs.

There is hope in the form of improved compliance with the 2010 Plain Language Act. Earlier this year, the Center for Plain Language released its report card of federal agencies' compliance with the law requiring them to speak in a language that most people can understand.

On the whole, agencies have gotten better: 86 percent are in compliance with the law's requirements -- up from only 54 percent just one year ago.

Improved readability not a small feat for agencies to have achieved. In an interview with Federal News Radio, government communications veteran and plain language volunteer Annetta Cheek said: “The result looks easy, but getting there is not so easy. Writing bureaucratically is much easier.”

As someone who has worked in the federal government for more than a decade, I have observed firsthand the tendency to lean on bureaucratic writing as way out of dealing with uncomfortable, confusing, complex and sensitive topic matter.

And I have seen how the resulting confusion on the part of the public leads to the automatic assumption that the government must be doing something wrong; must be hiding the truth, because "they can't just come out and say what's going on."

It's also obvious to anyone who reads social media that a lack of ready access to information creates fertile soil for conspiracy theorists. We can fix this problem by giving federal employees -- not just communicators but all employees -- significantly more information.

Federal employees are trustworthy, and they are trusted by the public. According to The Pew Research Center, 62 percent of the public have a "favorable" view of federal employees, even as their trust in the government as a whole has plummeted. People frequently tell me positive stories about their one-on-one interactions with feds.

To improve trust in government, and to improve workplace productivity, agencies should arm employees with information and encourage them to communicate freely -- anything that is not confidential.

Social media is effective as a communication tool precisely because of the power of uncensored word-of-mouth. Even when the news is bad, people trust the messenger who gives it to them straight. Who better to share information through regular media and social media than the federal employee who is deeply familiar with their own workplace environment?

Fears that employees cannot be trusted with meaningful information are unfounded. Study after study shows that federal employees are extraordinarily dedicated, regardless of the trying circumstances. As the Office of Personnel Management noted with regard to the 2014 Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey, which included 392,752 employees from 82 agencies:

The vast majority of federal employees believe their work is important, put in extra effort to get their jobs done and actively look for ways to do their jobs better. Seventy percent of respondents said that their work gives them a feeling of personal accomplishment.

Indeed, The Washington Post ran a story in December 2014 about Homeland Security Department employees who said they'd stay on the job even if they had to work without a paycheck.

The government invests no special effort to turn ordinary federal employees into brand ambassadors. And it doesn’t have to.

The integrity of individual federal employees already acts as a kind of "reputation insurance" for the apparatus of government as a whole. The only thing that needs to happen is removal of artificial barriers to communication with the public.

The path to increased return on investment for civil service salaries is clear and straightforward:

- Boost communication with individual federal employees.

- Encourage individual federal employees to communicate with the public about what they know, as long as it's not confidential.

- Watch the workplace satisfaction of feds increase.

- See their productivity increase accordingly.

- Notice significantly improved public perceptions of the federal government as a whole.

Dannielle Blumenthal, Ph.D., is a communications specialist in government, as well as a blogger and speaker on branding and social media. The views expressed are her own and do not represent a federal agency or the government as a whole. Follow her on Twitter at @oursocialfuture.

(Image via Mikael Damkier/Shutterstock.com)