Image via iluistrator/Shutterstock.com

4 Ways to Get Better People in the SES

The government needs to do better at getting the best people into the SES.

Earlier this month, the Senate and the White House devoted significant time and political capital to trying to break the logjam of stalled confirmations of presidential nominees. Indeed, filling our nation’s top political positions is crucial.

But a task that’s perhaps almost as crucial—yet gets much less attention—is ensuring that the government gets the best people into senior career positions, particularly those at the level of the Senior Executive Service (SES).

The federal government’s effectiveness at tackling major issues—such as reducing unemployment, supporting disaster recovery, and keeping the nation secure—depends, in large part, on the abilities of the 7,200 men and women in the SES. The complexity of these issues requires federal leaders who are not only technical experts but also strategic thinkers and skilled problem solvers.

Recent research by the Partnership for Public Service and McKinsey & Company examines how well the federal government is preparing a “pipeline” of leaders to take over SES roles. In our report, titled “Building the Leadership Bench: Developing a Talent Pipeline for the Senior Executive Service,” we discuss a number of factors that get in the way of building a robust SES pipeline.

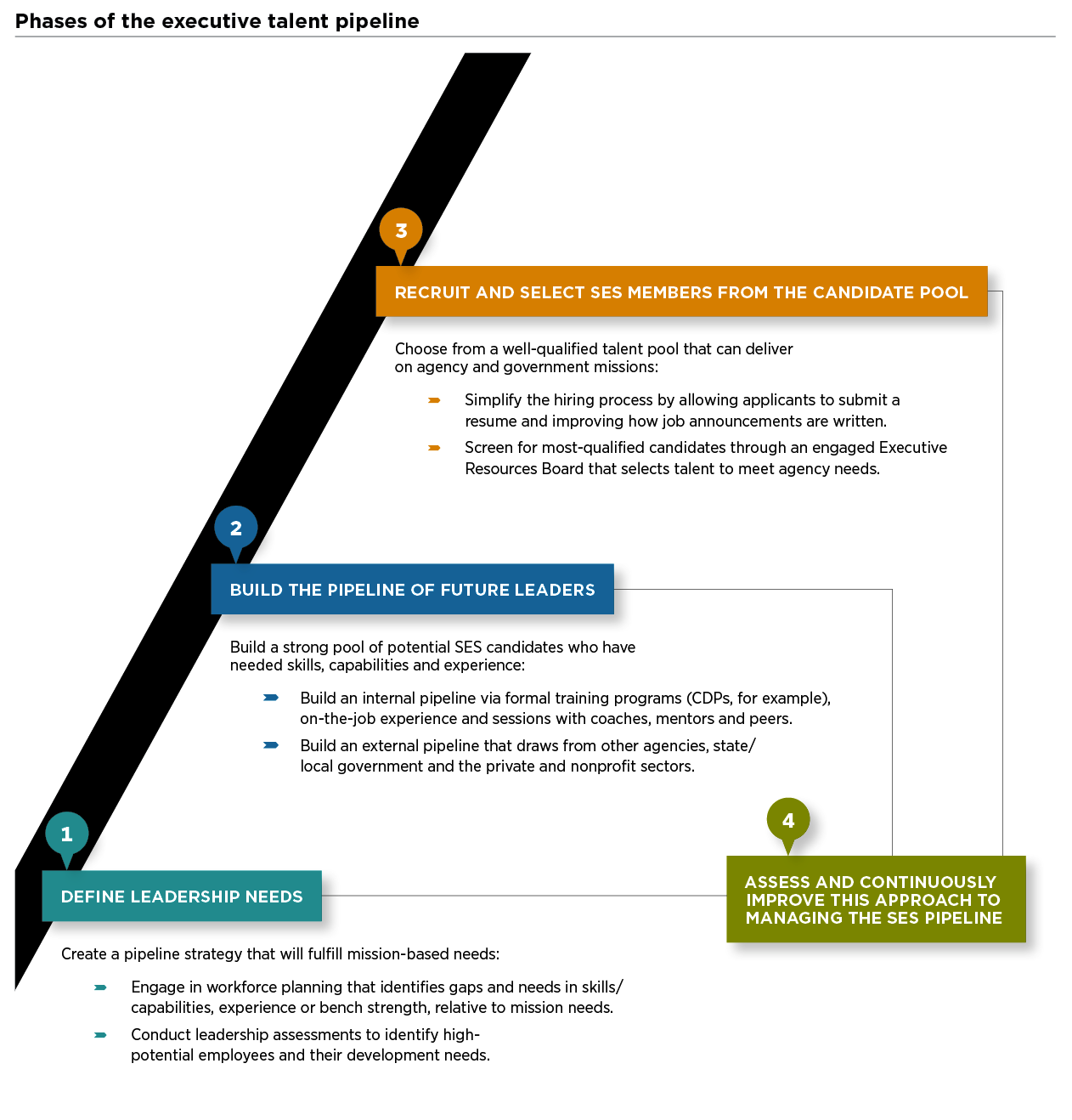

One factor, for example, is the lack of a standardized approach to talent development. But we also found that some agencies are using thoughtful and innovative practices in one or more of the four phases involved in developing a leadership pipeline.

First, an agency must define its leadership needs and assess how well current employees meet those needs.

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is widely cited by other agencies as excelling in this area. Its annual Leadership Succession Review (LSR) process yields valuable insights into the agency’s bench strength. As of November 2012, LSR data showed that the IRS had 10 candidates ready for every department-manager position and 5 candidates for every senior-manager position; the LSR also brought to light a weaker leadership bench in certain geographic locations.

Second, agencies should tap into both internal and external talent pools. Agencies should prepare internal candidates for SES positions using a combination of formal training sessions, on-the-job experience, and coaching from mentors and peers.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), for example, begins cultivating potential executives well before they reach the senior level; its 12-month Leadership Potential Program, targeted at GS-13 to GS-15 employees with little or no supervisory experience, offers classroom-style training as well as rotation assignments.

As for attracting external candidates, some agencies including the National Science Foundation have benefited from the Intergovernmental Personnel Act, which allows for short-term personnel transfers between federal agencies and state or local governments, academic institutions, and other outside organizations.

The third phase consists of selecting SES members from the candidate pool. Some agencies have simplified and streamlined the application and selection processes for SES jobs.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), for example, has rewritten job announcements to make them more inclusive and less agency-specific. As a result, according to one VA interviewee, since 2010 the fraction of SES executives coming from outside the agency has risen from almost zero to about 30 percent.

Finally, agencies should evaluate the effectiveness of their leadership-development approaches. Are their programs producing leaders in the right numbers, in the right time frames and with the right skills?

NASA, as part of its “Return on Engagement Model,” asks participants for feedback on its leadership-development programs, whether they would recommend the programs to colleagues and if they’ve applied the skills they learned.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) looks to several sources for feedback, including employee interviews, internal and external audits, and client surveys—all of which help GAO make continuous improvements.

The federal government and its agencies could build upon these pockets of success by creating central responsibility and accountability for developing a strong SES pipeline, establishing a comprehensive leadership-development approach that incorporates best practices, making sure that senior agency leaders prioritize talent management and opening SES pipelines more fully to external candidates.

Acting on these options can help our government ensure that the next generation of leaders is ready to meet the complex challenges ahead.

Public sector human capital experts Cameron Kennedy and Nora Gardner are leaders in McKinsey & Company’s Washington, D.C. office. Kennedy is Senior Public Sector Practice Manager and Gardner is a Principal in McKinsey’s Talent and Leadership Practice. For a copy of the Building the Leadership Bench report, go to ourpublicservice.org.

Image via Mopic/Shutterstock.com