Image via Banana Republic images/Shutterstock.com

Sometimes it is refreshing to look at how other countries approach the challenge of measuring and managing performance in their governments—especially when our government is so, let’s say, non-functional right now. Last week, I had the opportunity to attend a World Bank seminar where the Secretary of Performance Management for the Government of India described how his country is doing it.

Background. In June 2009, the President of India, Pratibha Patil, announced to a joint session of Parliament her commitment to create a Performance Management and Evaluation System for its national government, comprised of more than 4 million civil servants working in 84 departments and ministries.

Her announcement was tied to the creation of a cabinet-level office, headed by Dr. Prajapati Trivedi, who was designated the first Secretary of Performance Management. This position seems roughly equivalent to that of President Obama’s designation of a Chief Performance Officer when he took office in 2009.

Dr. Trivedi, a former economist at the World Bank, designed a performance management system with interesting parallels and differences from the U.S. performance management system that has evolved under the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA).

Organizational Framework. Dr. Trivedi helped create the Performance Management Division in the Indian Cabinet Secretariat, which launched the Performance Monitoring and Evaluation System (PMES) in September 2009. The PMES was developed, in part to reduce institutional fragmentation and multiple reporting across the government. The Performance Management Division seems to be roughly equivalent in the U.S. system to the staff arm of the Performance Improvement Council, and the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Office of Performance and Personnel Management.

To implement the PMES, the Performance Management Division developed a “ Results Framework Management System ” which is intended to provide a “unified and single view of performance” for contributors to the system (probably roughly equivalent to OMB’s MAX Federal Community ). The major component of it is the “Results-Framework Document,” which is roughly equivalent to U.S. agencies’ annual plans required under GPRA.

Agency-level Results Framework Documents (RFDs) are prepared and signed by the respective ministers and sent to the Performance Management Division for review. But to minimize gaming (e.g., setting low targets in order to easily achieve them), they are also reviewed by a third-party quality-scoring team – the Ad Hoc Task Force – which is comprised of about 200 outside experts and former government officials. The outside experts often make recommendations which are then incorporated by the ministries before being finalized.

After the RFDs are finalized, they are then sent to a High Power Committee on Government Performance , comprised of cabinet-level officials, and chaired by the Secretary of the Cabinet. The closest parallel in the U.S. system might be the President’s Management Council, which is comprised of departmental deputy secretaries serving as their department’s chief operating officers.

All of the agency-level RFDs are posted on a centralized website, performance.gov.in , which seems to be inspired by the U.S. government’s Performance.Gov website (the link is currently unavailable due to the federal government shutdown).

Strategic and Annual Plans. The Indian government has historically created five-year plans for the government as a whole. It is currently operating under its 12 th Five-Year Plan (2012 – 2017). The national Planning Commission also prepares Annual Plans for the economy, as well (here’s a link to the 2013-2014 plan ).

But under PMES, each agency and ministry prepares its own strategic plan, as well, which are supposed to reflect priorities in the governmentwide Five-Year Plan. Here’s a link to all agency strategic plans.

The agencies are grouped into six “syndicates,” which seem to roughly parallel the U.S. budget functions framework. The agency-level strategic plans, though, do not seem to be linked directly to budgeting or personnel resources. Budget resources are reflected, however, in the governmentwide Planning Commission’s annual plan.

The Results-Framework Document. The key element of the Indian PMES is the Results-Framework Document (RFD). Each agency is responsible for creating one; they seem to be roughly parallel in the U.S. system to Agency Annual Plans. Each department or ministry’s RFD addresses three elements:

- What are the department’s main objectives for the year?

- What actions will be taken to achieve these objectives?

- How do you determine progress?

The “main objectives” are derived from agency strategic plans. The “actions to be taken” are based on criteria/success indicators developed by agency leaders. Interestingly, these indicators are then assigned numerical weights by agency leaders to signal their significance. Agency leaders are also responsible for defining target values for what constitutes “success.” Here is a link to all 73 ministries who have submitted an RFD this year.

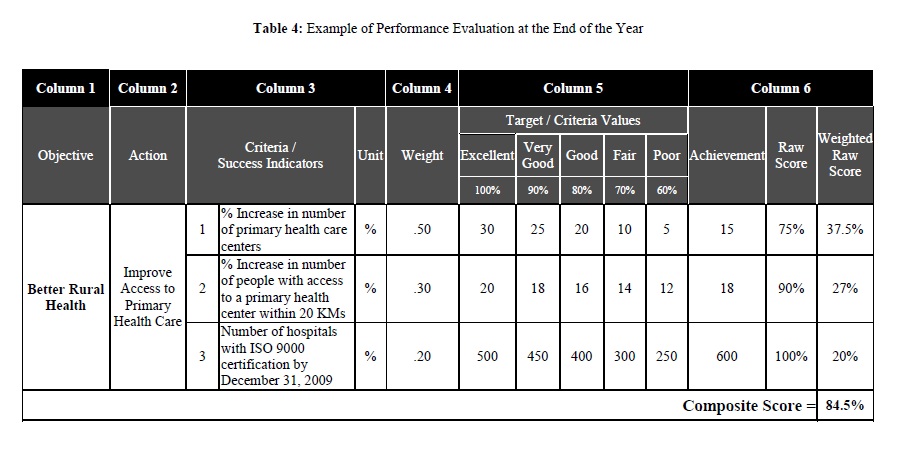

As the year progresses, progress against the targets are measured, and at the end of the year, the level of achievement is calculated first as a raw score, which is then weighted and is used to create a composite raw score.

According to the Performance Management Division’s website: “A Results-Framework Document (RFD) is essentially a record of understanding between a Minister representing the people’s mandate, and the Secretary of a Department responsible for implementing this mandate. This document contains not only the agreed objectives, policies, programs and projects but also success indicators and targets to measure progress in implementing them.”

The RFDs have six sections:

- Section 1 - A Ministry’s Vision, Mission, Objectives and Functions.

- Section 2 - Inter se priorities among key objectives, success indicators and targets.

- Section 3 - Trend values of the success indicators.

- Section 4 - Description and definition of success indicators and proposed measurement methodology.

- Section 5 - Specific performance requirements from other departments that are critical for delivering agreed results

- Section 6 - Outcome/Impact of the Department/Ministry

As an example, here’s a link to the most recent RFD for one agency, the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation . They are short, and are largely in tabular form.

Agency-Level End-of-Year Scores. As noted earlier, the performance information collected for each RFD is scored as “successful” or not, and each performance element is weighted relative to its significance. They are then combined into a Composite Index for a single performance evaluation score for the department or agency. Here is a sample of what one of the scorecards looks like:

The scores are taken seriously because they are linked to pay levels, which are set in relation to pay levels in the private sector. Progress is measured every six months, with a final report to the Prime Minister

The Government-wide Scorecard. At the end of the year, the agency-level composite indexes are consolidated to create a governmentwide ranking of how well agencies did against the targets in their RFDs. The composite scoring index allows a cross-agency ranking. There is no U.S. equivalent. This scorecard, as you might imagine, makes headline evening news in India when it is released.

Interestingly, of the 28 states and 7 territories in India, about 16-17 are undertaking a similar effort.

NOTE: If you are interested in what other countries are doing in the performance management arena, here is a link to a series of blog posts I wrote last year based on an earlier set of World Bank seminars on the topic.

Image via Banana Republic images/Shutterstock.com