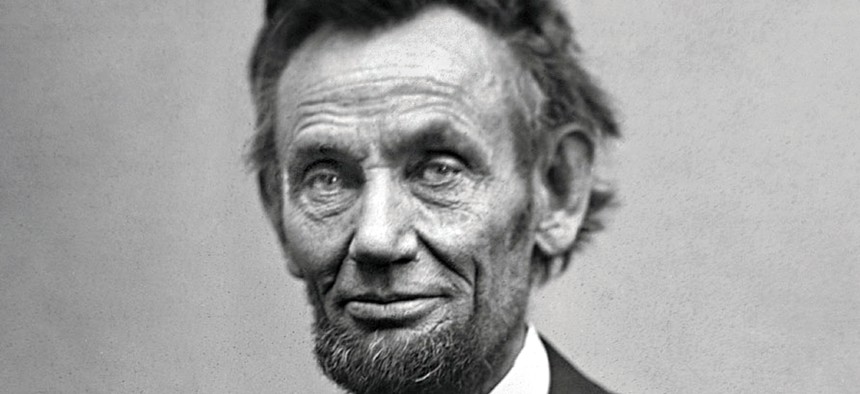

Library of Congress

How the World Mourned Lincoln in 1865

The president's assassination 150 years ago sparked outpourings of grief across the globe.

On the night of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth shot Abraham Lincoln in the back of the head. Lincoln—president of the United States, preserver of the Union, and liberator of four million slaves—died the next morning. He would be the last casualty of a war that cost some 750,000 American lives—more than all other American wars combined, and among the deadliest wars of its century.

Confusion reigned as telegraphs and steamships slowly spread the news across the Atlantic and the Americas over the course of weeks and months. When the full horror of Lincoln’s murder became known, letters of condolence came pouring in from trade unions in Italy, from town councils in Britain, from Masonic lodges in France, and from all other manner of groups and citizens throughout Europe and the New World. The legislatures of France, Italy, Belgium, Prussia, and Britain penned lengthy memorials to the fallen president. Foreign consuls and ministers flooded into American diplomatic posts from Brazil to Russia to share their sympathies.

Thirty years after Ford’s Theater, a wave of anarchist assassinations and bombings would sweep across Europe and eventually trigger the First World War. But in 1865, the assassination of a head of state still retained its power to stun and horrify. “The blow is sudden, horrible, irretrievable,” wrote the London Evening Standard . “Never, since the death of Henry IV [of France] by the hand of Ravaillac—never, perhaps, since the assassination of Caesar—has a murder been committed more momentous in its bearing upon the times.”

The Earl of Derby, leader of Britain’s opposition during the war, told the House of Lords that “the misfortunes of the United States affect us more than the misfortunes of any other country on the face of the globe.” Even though the British government had flirted with recognizing the Confederacy earlier in the war, dozens of towns and civic organizations throughout the British Empire sent memorials in the months that followed. Even industrial areas hit by the loss of Southern cotton were grief-stricken. “We have suffered long and severely in consequence of the cruel war which has cursed your land; for it has crippled our industry, blasted our hopes, and caused many of our sons to seek a home among strangers,” lamented the townspeople of Mossley near Manchester. “But our sufferings sink into insignificance when we think of this horrid crime, which stands without a parallel in the history of the world.”

Among ordinary people, Lincoln’s death weighed heaviest. “The Spanish people have been thunderstruck,” reported the American ambassador in Madrid. “I have heard ordinary men, ignorant that an American was listening, offer to lose a right hand if only this news might not be true.” His counterpart in Chile witnessed similar outpourings of sorrow: “Strong men wandered about the streets weeping like children, and foreigners, unable even to speak our language, manifested a grief almost as deep as our own.”

Why was Lincoln’s death mourned so deeply in foreign lands? He never traveled overseas, either before or during his presidency. Except for the ministers and consuls who journeyed to Washington, few Europeans ever had the opportunity to meet him. Television and radio did not yet exist to carry his face and voice throughout the world. Foreign mourners could only know him through newspapers and word of mouth.

For many, this was enough. In both Lincoln and the American experiment writ large, many Europeans saw an idealized view of their own aspirations. Sympathy came easily in Italy, where a war for national unification had also just been completed. “Abraham Lincoln was not yours only—he was also ours,” wrote the citizens of Acireale, a small town in Sicily, “because he was a brother whose great mind and fearless conscience guided a people to union, and courageously uprooted slavery.” For the German states, whose own national unification would come within the decade, the American conflict was also their own. “You are aware that Germany has looked with pride and joy on the thousands of her sons, who in this struggle have placed themselves so resolutely on the side of law and right,” proclaimed members of the Prussian House of Deputies in their memorial for the fallen president. The U.S. consul in Berlin noted that one of the deputies had a son currently serving in the Union Army, while another had lost his only son at Petersburg.

Workers and activists in Europe’s nascent socialist movement felt they had lost a genuine ally. The International Workingmen’s Association in London had saluted Lincoln, “the single-minded son of the working classes,” upon his re-election in 1864 and its “triumphant war cry [of] ‘Death to Slavery.’” Now they lamented the murder of “one of the rare men who succeeded in becoming great without ceasing to be good.” Among the condolence letter’s signatories was the group’s secretary for Germany, Karl Marx.

This sentiment was not fully shared among the upper classes in countries with an entrenched nobility. During the conflict, some aristocrats throughout Europe felt more kinship with the plantation owners of Mississippi than the workingmen of Pennsylvania or Massachusetts. Conservative governments nevertheless mourned Lincoln as a symbol of law’s triumph over rebellion. Nowhere was this contrast more visible than in Portugal, where the House of Peers praised the American president as a just and merciful conqueror, while the Jornal da Lisboa published a labor leader’s speech that exalted Lincoln as the “emancipator of the slaves.”

Lincoln’s approach to slavery evolved over the course of his presidency, and he only pushed for full abolition in the closing year of his life. This nuance was lost on overseas mourners, who frequently hailed him as a martyr in the struggle against slavery. “As the emancipator of all the slaves in the United States, Abraham Lincoln is entitled to the gratitude of all mankind,” wrote the leaders of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in London. Colombian President Manuel Murillo praised Lincoln for “erasing the stigma of an odious institution.” Emancipation societies throughout Europe hailed his struggle and sacrifice.

The Lincoln-as-martyr narrative was irresistible, even in the most anodyne of analyses. “Had Lincoln been a vain man he might almost have ambitioned such a death,” mused the London Morning Star . “The weapon of the murderer has made sure for him an immortal place in history.” Perhaps the most extravagant tribute came from La Opinion , in Bogota, Colombia.

In the vulgar sense of human language, Abraham Lincoln was certainly not a great man. He had not the dazzling prestige of victorious achievements in war; he was not a conqueror of peoples and countries…But he possessed something greater than all of these, which all the splendors of earthly glory cannot equal. He was the instrument of God.

The Divine Spirit, which in another day of regeneration took the form of an [sic] humble artisan of Galilee, had again clothed itself in the flesh and bones of a man of lowly birth and degree. That man was Abraham Lincoln, the liberator and savior of the great republic of modern times. That irresistible force, called an idea, seized upon an obscure and almost common man, burnt him with its holy fire, purified him in its crucible, and raised him to the apex of human greatness—even to being redeemer of a whole race of men.

A preacher in the Kingdom of Hawaii managed to weave these narratives together into a cohesive whole. “It is also comforting to think that Abraham Lincoln, the poor man’s friend, the emancipator of the oppressed, the chosen champion of liberty and law, died at a time and in a manner most favorable for his own already illustrious fame,” he told a mourning crowd at a memorial service in Honolulu. “And so, as a martyr for liberty, is his memory most securely embalmed in the grateful hearts of an affectionate people.”

And what was to become of those people and their Union without the man who saved it? Chaos seemed possible, even probable, to international observers after Lincoln’s death. “His country is left to toss in the sea of a dismal anarchy; a revolution of which no man can presume to foretell the issue,” feared the London Evening Standard . Others foresaw the struggles that Reconstruction would bring. “His work is done, the cause is gained, the war at an end, but woe to the South! It has killed its best protector during this awful moment,” wrote Fredrika Bremer, the Swedish feminist writer. Would the North wreak vengeance upon the South? Would Andrew Johnson be able to carry on his predecessor’s legacy? Would the United States remain whole?

Rebuilding the Union would not captivate the world as much as the great struggle that saved it. The war faded in the international mind, but the memory of its greatest leader never did. “When his assassin took flight he is said to have exclaimed, ‘Sic semper tyrannis!’” wrote the editor of l’Epoque in Paris. “God grant that the American government may never have any other but tyrants such as he.”