We all knew the moment would come. It could have been over Iran or North Korea, a hurricane or an earthquake. But it may be the new coronavirus out of China that tests whether President Donald Trump can govern in a crisis—and there is ample reason to be uneasily skeptical.

The U.S. government has the tools, talent, and team to help fight the coronavirus abroad and minimize its impact at home. But the combination of Trump’s paranoia toward experienced government officials (who lack “loyalty” to him), inattention to detail, opinionated rejection of science and evidence, and isolationist instincts may prove toxic when it comes to managing a global-health security challenge. To succeed, Trump will have to trust the kind of government experts he has disdained to date, set aside his own terrible instincts, lead from the White House, and work closely with foreign leaders and global institutions—all things he has failed to do in his first 1,200 days in office.

We do not know yet how grave a threat the new coronavirus will turn out to be. On the one hand, scientists have quickly sequenced the virus and are working on a vaccine. China has imposed draconian quarantines to slow the virus’s spread, and is rapidly building massive new hospitals to treat its victims. To date, the U.S. has seen only a handful of cases, all of them the product of travel to China, not transmission here. These are causes for concern, but not overwrought fear.

But on the other hand, there are some worrisome developments. Models suggest that the cases in China may number in the hundreds of thousands—many times what the government has reported. Perhaps a million or more people left Wuhan before the quarantines, and could be spreading the virus widely. Other countries are reporting cases of the virus among people who were not in China; there are even reports that individuals may be infectious before the onset of symptoms (a substantial complication to traditional public-health screening). And the economic impact of a massive epidemic in China on the global economy is difficult to predict.

What will Trump do about it? His track record offers us two data points, one horrible and one merely disappointing.

Trump briefly withdrew from politics after his “birther” campaign against President Barack Obama was discredited, but his next big public splash was a virulent, xenophobic, fearmongering outburst over the West African Ebola epidemic of 2014. Trump’s numerous tweets—calling Obama a “dope” and “incompetent” for his handling of the epidemic—were both wrongheaded and consequential: One study found that Trump’s tweets were the single largest factor in panicking the American people in the fall of 2014 . How paranoid and cruel was Trump? He blasted Obama for evacuating an American missionary back to the United States when that doctor contracted Ebola while fighting the disease in Africa. Fortunately, Obama ignored Trump’s protests, and Kent Brantley was successfully treated in the U.S.; he continues doing good works today.

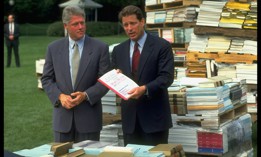

Obama’s strategy for combatting Ebola in West Africa—interventionist, aggressive, science-based—made a huge contribution to a global response that saved hundreds of thousands of lives, and protected the U.S. from an outbreak. Tom Friedman wrote that it was perhaps Obama’s “most significant foreign policy achievement, for which he got little credit precisely because it worked … [showing] that without America as quarterback, important things that save lives … often don’t happen.”

As president, Trump’s own handling of the second-worst Ebola outbreak in history—ongoing in Congo—has been more mixed. Regrettably, after four U.S. soldiers were killed in Niger in 2017, Trump imposed an isolationist edict that no U.S. personnel are allowed to be in harm’s way in fighting the disease. Top American experts who were in and near the disease “hot zone” in Congo have been withdrawn. Moreover, while the U.S. has sent aid, it has provided only a fraction of the assistance offered in past global-health emergencies, a step back from the leadership demonstrated by prior Democratic and Republican administrations. Within these constraints, however, Trump has allowed the experts at the U.S. Agency for International Development and the Centers for Disease Control to provide assistance; most surprisingly, Trump even allowed the medical evacuation of a possible Ebola case to the U.S. for treatment.

The record on the Congo response is uneven: As long as Ebola in Congo is not in the news, the White House allows the bureaucracy to do its job, albeit within a limited range of action and with less than robust U.S. participation. But escalation of the coronavirus epidemic, and the elevated level of public attention, may lead Trump to depart from his usual indifference to the functioning of government and choose to assume personal leadership of his administration’s response.

Some of the world’s leading infectious-disease experts continue to serve in the administration, led by the incomparable Tony Fauci at the National Institutes of Health, and the level-headed Anne Schuchat at the CDC. These two, along with other leaders at key science agencies (and scores of men and women working for them), have decades of experience serving under presidents of both parties, and are among the world’s best at what they do.

But Trump’s war on government has decimated crucial functions in other key agencies. Smart and effective border screening will be a key tool in the response; there is scarcely a single competent or experienced leader left at the Department of Homeland Security. While USAID is in solid hands under Administrator Mark Green, it is stuck inside Mike Pompeo’s State Department, which has been purged of the many skilled administrators who play a role in facilitating foreign-disaster response. Trump’s poor choices for many ambassadorial posts, and harsh treatment of the Foreign Service, may create holes in our on-the-scene leadership as the disease spreads: During the West African Ebola epidemic, career Foreign Service ambassadors were important players in the response.

The biggest gap, of course, is at the White House itself.

At the end of the West African Ebola epidemic in 2015, President Obama accepted my recommendation to set up a permanent directorate at the National Security Council to coordinate government-wide pandemic preparedness and response. For the first year of his presidency, Trump kept that structure, and put the widely respected Admiral Tim Ziemer, a veteran of the George W. Bush administration, in charge of the unit. But in July 2018, John Bolton took over the NSC, disbanded the unit, and relegated Ziemer to a staff job at the State Department. The administration described that as a move to “streamline” the NSC, while critics charged that Bolton was too focused on hard-power threats.

To date, the Trump administration has resisted reversing this decision—either permanently, or on an ad hoc basis for the coronavirus response. Standing up a unit at NSC would require bringing in career staff to work there, and Trump’s paranoia about having such government veterans in the White House weighs against the move. But perhaps just as important, greater White House involvement in managing the response to pandemics would likely mean greater personal involvement by Trump. And in that regard, senior officials in government agencies may have a view of presidential engagement not unlike Fiddler on the Roof ’s prayer for the czar: “May the lord bless and keep him … far away from us.”

In his press conference on Tuesday, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar—whose generally solid performance reflected his experience in government and his comfort in working with experts—waved off the need for a White House coordination of the response, saying that cooperation among agencies could be managed at a lower level.

Yet with no one in charge at the White House, there is no authority to resolve disputes between federal agencies; no one to hold agencies accountable for the pace and intensity with which they implement the response; no one to resolve competing requests for congressional funding; and no one to draw on the resources of the security agencies of the government to help support the response.

Azar’s own comments contained an interesting example of the costs of that absence of White House leadership. Azar said that the CDC had offered to send experts to China, to no avail. Not a surprising reaction to a request from the CDC to Chinese public-health officials. But why wasn’t this proposal made at a higher level, pressed in a call from Trump’s national-security adviser to his Chinese counterpart? Or perhaps even in a call from Trump himself to China’s President Xi Jinping?

Ultimately, the question may never be called on the coronavirus, which could be less of a threat than early indications suggest. But if so, that will be the virus’s choice, not Trump’s. If the crisis escalates, there will be no keeping it from the Oval Office and Trump’s direct intervention, for better or worse.

Five presidents—liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans—have looked to Tony Fauci for advice; it is not impossible to imagine Trump being the first to angrily dismiss the counsel he offers if it does not fit with his own poor instincts. A president who calls generals “babies and cowards” will have to sit face to face with experienced global-health-security professionals, and listen. He will have to put his isolationist biases and anti-science mind-set aside, and let expertise—not his personal inclinations or the political whims of his base—guide U.S. policy. He will have to trust bureaucrats, diplomats, career staff, and agency appointees who are not on Team MAGA.

He will have to govern, as Democratic and Republican presidents have before him, but unlike how he has conducted himself at any point in his presidency to date. Many lives—mostly abroad, but perhaps here as well—could depend on it.