Census Bureau file photo

This Rural Town Swelled With Immigrants. But Will Census Count Them?

The 2020 census was supposed to show this rural town what it is now. Then came COVID-19.

This story originally appeared on Stateline.

MILAN, Minn. — The October chill hit Gabriel Elias like a truck when he reached the airport parking lot in Minneapolis. He recalls surveying the cold, unfamiliar landscape. The trees looked near death.

As his uncle drove nearly three hours across the Minnesota prairie, Elias began to worry. Why did his family live so far from the city? Century-old farmhouses stood in for the one-story tin-roofed houses common in the land of his birth.

In 2002, Elias was among the first people from the Federated States of Micronesia to move to Milan, Minnesota, the self-proclaimed Norwegian capital of the United States. Milan’s population had been declining when the first sprinkling of Micronesian newcomers arrived. Then more came.

Ten years ago, Micronesians made up a fifth of Milan’s population, then 369 souls. Now, it’s estimated that more than half the town’s 360 residents are native Pacific Islanders or their children. Without them, Milan might have dried up and blown away.

“They’ve saved our community,” Milan Mayor Ron Anderson said of the Micronesians. “They’ve also made us vibrant. We were losing our vibrancy because we were getting old.”

Milan’s growing Micronesian population has bolstered the town’s faltering economy. The Micronesians also could bring federal help — but only if they are counted in the 2020 census.

The federal government relies on the census count to distribute more than $1.5 trillion in federal grants, direct payments, loans and loan guarantees. But Milan’s Micronesians are among the rural residents who are hard to count, and the pandemic has increased the challenge. With social distancing measures in place, and other health-related needs to address, the census outreach planned for the spring and summer never happened.

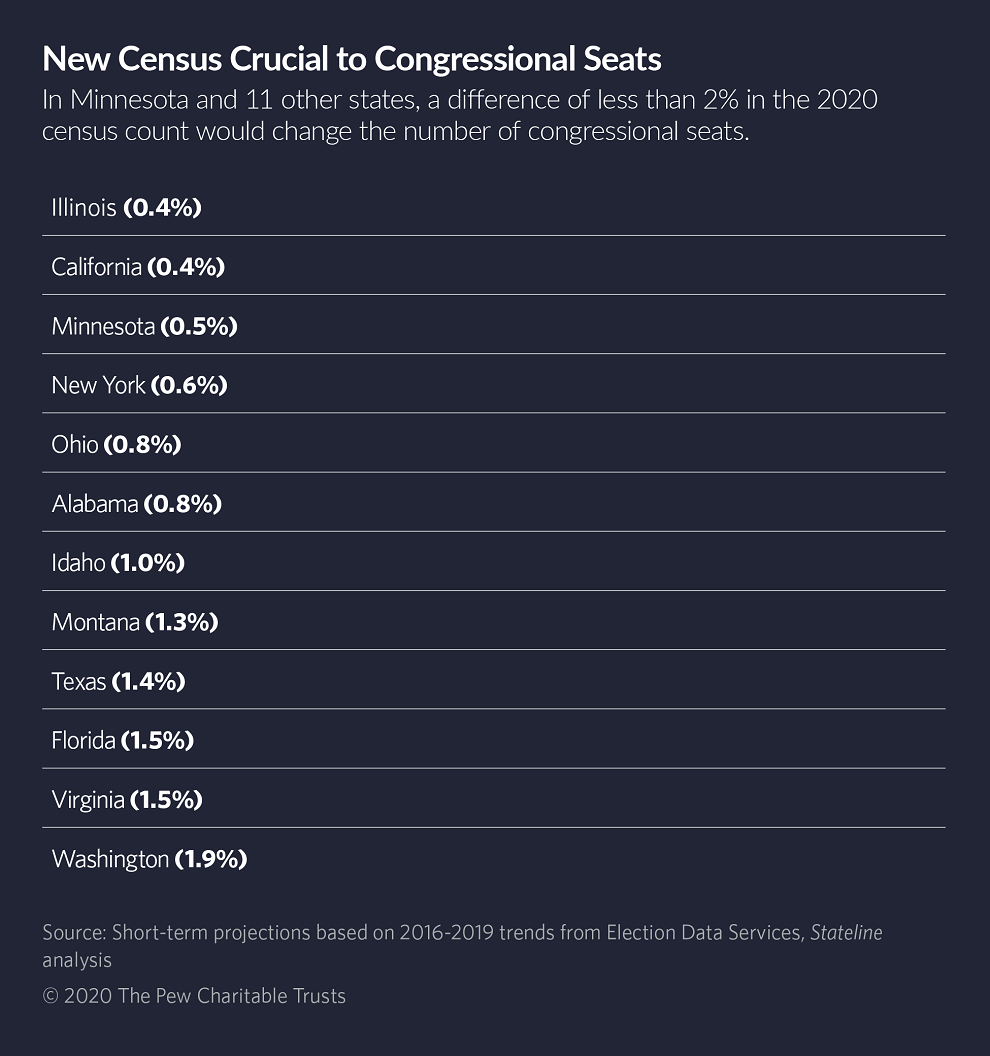

Minnesota also is among the 12 states where a difference of less than 2% in the 2020 census count would change the number of congressional seats.

“All rural communities are struggling to keep their population,” Anjuli Mishra Cameron, research director of the state's Council on Asian Pacific Minnesotans, told Stateline in a phone interview. “So, this kind of boom for the town requires infrastructure changes that they need to anticipate — and the census is a key part of that.”

Velkommen til Milan

One after another, Micronesian boys enter the Milan Public Library after an icy school day in January. They rip off their winter coats and backpacks as they dart past two older white men seated across from Mayor Ron Anderson, and straight for the row of computers behind him.

“Hey buddy! Number three is working,” Anderson says from his perch at the front desk. He’s also the town librarian.

“Hey buddy! How ya doin’?”

“Hey buddy!”

Three decades ago, Milan had virtually no minority residents, Anderson said. Now, “in this town, you’ve got a lot of brown … and that’s the biggest culture shock for us.”

“Velkommen til Milan” reads a sign above a display packed with Scandinavian art, gifts and wares down the block from the public library. A multi-room treasure chest with a hint of a garage-sale feel, the century-old spaces are among the anchor institutions on Milan’s main street. Ann Thompson, owner of the Billy Maple Trees Gift Shop attached to the Arv Hus Museum, happily walks a visitor through the offerings.

A fourth generation Milander, Thompson’s family history is embedded in the buildings. The museum was once a harness shop run by Thompson’s great grandfather.

The caption of a black and white photo that’s beginning to yellow lists Milan’s assets in 1904:

“Three churches, three restaurants, two hardware stores, three general stores...” it begins, “... one bank, two furniture stores, two machine sheds, one photography shop, one hotel."

Most of those institutions aren’t around anymore.

“We would not have a grocery store; we would not have the basic pieces to the puzzle if it were not for our immigrant community,” said Thompson, a petite woman who’s like a mother goose to the Micronesian children. “I think we’re so lucky.”

Steps away, in the old tractor and car dealership turned grocery store, a steady flow of Micronesian women in traditional skirts brave the freezing temperatures.

“We never sold mangoes before,” said Beth Dalen, the cashier at Bergen’s Prairie Market. “Now we probably buy eight cases at a time or 12.”

Other popular items line the shelves: three types of curry powder, 50-pound bags of rice, coconut milk, canned Spam, frozen baby octopus and bonito flakes, or dried, smoked tuna.

“They love, love, love salt,” Dalen said.

The Micronesian customers speak little English. They smile at Dalen during their interactions, although they avoid walking past her — Dalen explains that it’s considered rude in Micronesian culture. “Kinisou,” or thank you in Chuukese, Dalen says as the women return to winter’s icebox.

Milan or Milanesia

Milan's Micronesians come from the island of Romanum, nearly 3,500 miles across the ocean southwest of Honolulu. It’s among the more than 600 islands that make up the Federated States of Micronesia, between Hawaii and the Philippines. Similar to Milan, Romanum takes up less than a square mile.

Locals can climb to the top of a hill, look out in every direction and see the land disappear into the West Pacific. Conventional grain farms surround Milan.

Erik Thompson (no relation to Ann Thompson) served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Micronesia between 1979 and 1981, with stints on the island of Romanum in Chuuk State. He later returned to Micronesia during graduate school, all the while keeping in touch with his “Peace Corps brother” in Romanum who had helped him adjust.

The man, Elias’ uncle, asked Erik Thompson if he could visit. In 2000, he settled his family in Milan and began working for a sanitation company that contracts with the local turkey processing plant. So began the Micronesian’s migration to southwest Minnesota.

Migrants to the U.S. tend to favor more densely settled rural areas near large cities. Milan is about as far from Minneapolis as it is from Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

As the Micronesians came, they helped to offset native-born population losses. In Chippewa County, where Milan is located, the native-born population declined 6.1% between 2010 and 2018. During that time, there was an 86.25% increase in the foreign-born population.

In 2000, Pacific Islanders were 0% of Milan’s population. In 2018, their share was 38%, and it’s likely larger now. Minnesota’s foreign-born resident population is also climbing, from 2.6% in 1990 to 7.12% in 2010. They’re currently about 9.44% of the state’s population.

Families have been adjusting to a new climate and a difficult new language — a well-worn path for newcomers throughout American history. Many of the children speak Chuukese at home the way the old-timers in Milan once spoke Norwegian.

Soon after Elias arrived, he followed his uncle in working for the sanitation company that contracts with the Jennie-O plant in the county seat, Montevideo.

A spokesperson with Jennie-O did not respond to Stateline’s request for data on the race of its workers since the plant opened in 1996. But locals say the majority of its workers are now Hispanic and Micronesian.

Shifting Attitudes

Elias had planned to stay in Milan only a few months, but he says he changed his mind after being overcome by a positive, spiritual change. Taking advantage of the new start, he stopped partying and drinking and did a better job managing his money.

“You got to get up every day and go to work, otherwise you won’t eat,” Elias said. “Back home, you could pick your day, pick your time, do what you want to do. Live life. Life is free.”

Elias went back to Romanum and eventually returned to Milan with a wife and newborn. Initially, Milan welcomed Elias and his young family.

“I started thinking that I’m a Minnesotan and I started doing things like the way Minnesotans do,” said Elias, who is tall and heavyset. He sat in the living room of the immaculate three-story home he shares with his wife, daughter and several new Micronesian newcomers.

But as Milan's Micronesian population grew, attitudes shifted.

Native Milanders began avoiding the local playground where the Micronesians gather. People complained the Micronesians didn’t maintain their homes or yards and used blankets to cover their windows rather than curtains. Some yelled or cursed at the Micronesians to properly dispose of diapers and beer bottles. (There is no recycling on Romanum, so islanders just buried their trash or threw it in the ocean.) Natives also complained that the Micronesians were rude when they didn’t speak, though Elias says many Micronesians are simply afraid to speak English.

Some of the Micronesians have tried unsuccessfully to run their own businesses, such as a gas station and a cafe. Some locals say it’s because they lacked business experience and there weren’t enough customers in Milan to keep the enterprises afloat. Others offer a more cynical view; they say the old-timers didn’t want to support it.

The Micronesians are teaching “some of these old, stubborn Norwegians to have more tolerance,” said Dalen, the grocery store cashier. “To get to know their culture, and their wanting to know ours.”

Regardless of how much the Micronesians adapt, several old-timers agree their rural culture will never fully accept outsiders.

Some of the early clashes could have been handled better, Anderson said. “We didn’t do enough because we didn’t understand what was coming.”

“Honest to God, 90% of us … could not imagine why a person would leave a tropical island to come live in this,” said Anderson, from his perch at the library front desk. “I guess we didn’t know how bad it was there, what their conditions were, that this was favorable. We watched too much Gilligan’s Island or something with palm trees.”

Anderson has been in Milan for 35 years, and mayor off and on for 20. He and the Micronesians have one thing in common.

“I’ll never be a Milander,” Anderson added. “Because you got to be born here to be a Milander.”

That’s just rural culture, said the gruff old man sitting across from Anderson who didn’t want his name used. He slouched in his chair; his slight body almost disappeared into his oversized coat. “Really, we’re a little picky. We don’t like outsiders.”

Hard to Count

Minnesota boasts the nation's highest census response rate at 73.3% — nearly 10 percentage points higher than the national response rate of 64.2%. The bureau told The New York Times Saturday that it had reached enough nonresponders to raise the total share of households counted to 74.8%. The rate in Chippewa County, which includes Milan, is also high, at 71.1%.

But Cameron, the research director of the state's Council on Asian Pacific Minnesotans, estimates a 50% census response rate among Milan's Micronesian community, nearly 10 percentage points below the city's.

Nationwide, an accurate census requires a lot of outreach to the people deemed hardest to count. They include racial and ethnic minorities, people with limited English skills, undocumented immigrants, small children and people suspicious of government.

The pandemic canceled outreach efforts in Milan. Census workers did not knock on doors in the spring and early summer. The public library and churches in Milan did not set up computer stations dedicated to completing online forms. President Donald Trump cut short the deadline to count the nation's population by a month.

In Milan, Micronesians are unfamiliar with the census. They’re unsure whether they need to fill out the forms as non-U.S. citizens. They lack internet access. The census asks people to complete the form based on their home on April 1. But it’s confusing for Micronesian families who often move between homes.

Census workers began knocking on doors Aug. 9. Cameron and community leaders say they hope to hold outreach events before the Sept. 30 deadline, but nothing is currently planned.

Although the Micronesians are not refugees who’ve lived through war or had to flee their homes, their immigration status is in jeopardy. They benefit from a relationship between their homeland and the U.S. that allows them to live and work here legally but makes it almost impossible to become U.S. citizens.

In the mid-1980s, the U.S. established the Compact of Free Association with the Federated States of Micronesia. Micronesia receives U.S. economic assistance, and its citizens enjoy unrestricted U.S. travel. In return, the U.S. has military control over the region, said Vicente Diaz, a University of Minnesota professor of American Indian Studies who’s also from Micronesia.

But the home state of most Micronesians in Milan seeks to secede from Micronesia. If Chuuk gains independence, the legal status of Milan’s Micronesians would be in jeopardy. At the same time, living conditions in Micronesia are deteriorating due to sea level rise and climate change.

In Milan, the Micronesians are a majority that provides a stable tax base but lacks political power. Twelve municipalities across the country allow noncitizens to vote in local elections, but none in Minnesota.

“There just won’t be enough people to hold city positions if the Micronesians don’t,” said Erik Thompson, whose Peace Corps service in Micronesia is credited with prompting the migrants’ journey to Milan.

Most Micronesians work the night shift at the Jennie-O or one of its subcontractors, so they can’t make the monthly Milan City Council meetings in the evenings. Some describe the meetings as rigid and inaccessible to most Micronesian adults since they’re in English. Elias attended on behalf of the Micronesian community until his hours changed.

“They just don’t realize that it’s affecting the community as well,” said Elias. “They don’t really care much about it. So, we need the person to be able to be there and just speak up and make a push to anything we have.”

Stateline made repeated requests for interviews with Milan's four City Council members, by phone and through the city clerk. Only Bruce Dalrymple responded.

Anderson admits the lack of Micronesian representation at council meetings weakens local government. “A lot of times we make decisions, we don’t have any input,” Anderson said. “We make a decision that we think is right and it might not be right, or what the Micros need. I should throw the Hispanics in too.”

“We’re the dominant culture, but we’re not,” he added. “We’re a minority in population, but we’re still the dominant culture because we do all the ruling and pretty much all the business.”

Dalrymple put it more bluntly: “It’s becoming where the minority is telling the majority, ‘Well, we’re just doing it.’ They have no say whatsoever.”

The New Milanders

On a dangerously cold afternoon in February, five girls enter the warmest room in the Milan Community Center, once the school for local children before the dwindling population couldn’t justify it.

The girls, then ages 7-13 with long ponytails and braids, hold their island roots and southwest Minnesota in their dress: leggings under dark traditional skirts with colorful flower stitching, paired with warm hoodies and durable sneakers for trekking through snow.

Elias’ daughter, Galesa, arrived in Milan as a newborn. Still, she sometimes feels the distance between herself and her peers. “Like at my school, there’s people who think we’re here just to take over the place,” said Galesa, the eldest of the girls.

Once a boy came up to Galesa and said, “‘Donald Trump said go back to your country, so you should probably go back.’ And I said, ‘I don’t think I should do that.’” Galesa declined to repeat much of the rest.

“I told him that I have a big family, so you better watch your back,” Galesa said, giggling. “He’s like ‘OK, sorry, OK, I didn’t mean that.’ I apologized to him after that, and he said it’s fine. I think I better watch my mouth next time.”

Those types of clashes happen often, according to the girls. “But they’re starting to stop because they’re getting scared,” Galesa said.

At school the kids mix. The adults, well, they only mix a bit, Anderson said.

“But again, how much do we have in common?” Anderson said. “I’m not saying that to be nasty, but they like to eat. I don’t like to eat.”

But Milanders do come together. Ann Thompson, the museum and gift shop owner, teaches English adult education classes to mostly Micronesians and Hispanics. She manages after school programs for the Micronesian children such as a youth group and 4-H club. The broader community gathered in the park over the summer to honor Thompson's late father, a beloved community leader.

The pandemic canceled Milan's annual Norwegian Day Parade, or Syttende Mai. But most years, the Micronesians are the largest contingent. A seafaring culture like the Norwegians, the Micronesians wave a Norwegian flag and present their indigenous watercraft and woodworking skills.

“I just wish there were a lot of things we could do together as a community and enjoy it,” Anderson continued. “I think maybe more music. What community can’t enjoy music? And the Micros love music and they’re” — his voice lowers several notches so the children playing computer games behind him can’t hear him curse — “damn good at performing music. They’re fantastic.”