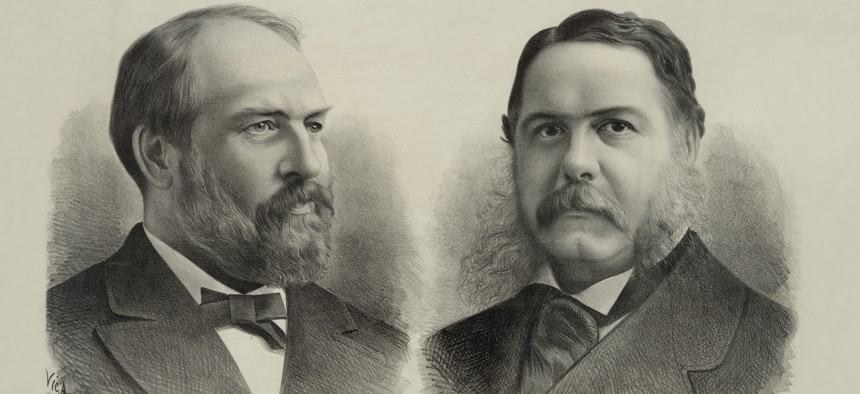

The assassination of James Garfield, left, led his successor, Chester Arthur, to sign the law creating the competitive civil service. Buyenlarge/Getty

That Time Reformers Took on Cronyism, Nepotism and Alcoholism in the Federal Workforce

How the Pendleton Act created the modern civil service.

The latest in an intermittent series looking back at groundbreaking, newsmaking, appalling and amusing events in government history.

In 1883, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Pendleton Act, designed to professionalize the federal workforce. The law was very clear about who had no business working in government:

“No person habitually using intoxicating beverages to excess shall be appointed to, or retained in, any office, appointment, or employment to which the provisions of this act are applicable,” it stated.

Truth be told, alcoholics weren’t the central concern of the reformers behind the Pendleton Act. Their prime target was the political cronies of elected officials, who were rewarded for their support—financial and otherwise—of successful candidates with patronage positions in government. To the political victors went the spoils of plum government positions—and non-plum jobs, too.

The law also targeted nepotism in federal employment. “Whenever there are already two or more members of a family in the public service in the grades covered by this act, no other member of such family shall be eligible to appointment to any of said grades,” it stated.

The idea was to overhaul a system where not only were unqualified people appointed to federal jobs, but employees could be fired at any time simply for supporting the wrong party. The system had been in place for decades, and efforts to create a professional civil service had failed to gain much traction. President Ulysses S. Grant signed a law creating a Civil Service Commission in 1871, but it was largely toothless. The commission’s funding ran out after two years, and Congress didn’t renew it.

The situation changed in 1881, when Charles Guiteau, angry that he hadn’t received an appointment to a federal job, assassinated President James Garfield. Guiteau, an unsuccessful lawyer, had delivered a couple of speeches in favor of Garfield’s candidacy, and believed that this entitled him to the post of ambassador to Austria. He appeared to be aware, however, that his qualifications weren’t strong, because he relied on a simpler argument in a letter to Garfield formally requesting the position. “On the principle of first come first served,” Guiteau wrote, “I have faith that you will give this application favorable consideration.”

With Garfield’s assassination, civil service reform suddenly became a hot-button political issue nationally. Arthur, who succeeded Garfield, backed the idea even though he had been an enthusiastic user of the spoils system in a stint as head of the federal customs house in New York. In fact, in 1878, President Rutherford B. Hayes fired Arthur from his customs position for giving away too many patronage jobs.

The Pendleton Act required open, competitive examinations for certain positions in the civil service, ensured that employees in these positions would not be required to contribute to political campaigns, and declared that “no officer or employee of the United States mentioned in this act shall discharge, or promote, or degrade, or in manner change the official rank or compensation of any other officer or employee, or promise or threaten so to do, for giving or withholding or neglecting to make any contribution of money or other valuable thing for any political purpose.”

The Pendleton Act not only funded the Civil Service Commission, but ordered that its three members not be stuck in some bureaucratic backwater. “It shall be the duty of the Secretary of the Interior to cause suitable and convenient rooms and accommodations to be assigned or provided, and to be furnished, heated, and lighted, at the city of Washington, for carrying on the work of said commission,” the law stated.

So with a stroke of the pen, Arthur brought an end to the spoils system and ushered in a new competitive, professional civil service. Well, not exactly. For starters, the law applied only to a fraction of the federal workforce. It covered employees at federal offices in Washington and customs houses and post offices in major cities.

In his book Roosevelt the Reformer, on Theodore Roosevelt’s years as a crusader for civil service reform, Richard D. White notes that the Pendleton Act initially covered 14,000 federal employees out of a total workforce of 133,000 people. From 1883 to 1901, the number of patronage positions in government actually increased, from 118,000 to 150,000. The commission lacked the authority to shift patronage positions into the merit system and had to busy itself with overseeing the examination process for those positions that were classified as competitive.

On top of that, opponents of reform continued to fight to undermine the Pendleton Act for years. Spoils system backers filled the halls of Congress, and presidents were slow to change traditional practices as well. It would take years before a truly independent, professional civil service emerged.

Eventually, though, competitive examinations became the rule for federal government positions. That lasted until 1981, when a class action lawsuit alleged that the Professional and Administrative Careers Examination discriminated against Black and Hispanic applicants for federal jobs. That led to a consent decree eliminating the exam. In the years that followed, a patchwork system of other competitive procedures and special hiring programs emerged, leading to the fragmented civil service system we have today.

The Pendleton Act has reentered the public debate again recently, as Republicans seek to turn the federal workforce into at-will employees, via either the Public Service Reform Act or the reincarnation of Schedule F, a job classification system proposed but never fully implemented near the end of the Trump administration to make employees in policy-related positions subject to removal by their political overseers. For the first time in more than 100 years, the very idea of a competitive civil service, insulated from political pressures, is under attack.