A woman stands outside the Social Security Administration office February 2, 2005 in San Francisco, California. Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

COVID-19 Widows Struggle to Get Benefits as Social Security Offices Remain Closed

The closure of Social Security offices during the pandemic has made getting survivors benefits difficult for the spouses and children of those who’ve died during the pandemic. More than 90 percent of those seeking survivors benefits are women.

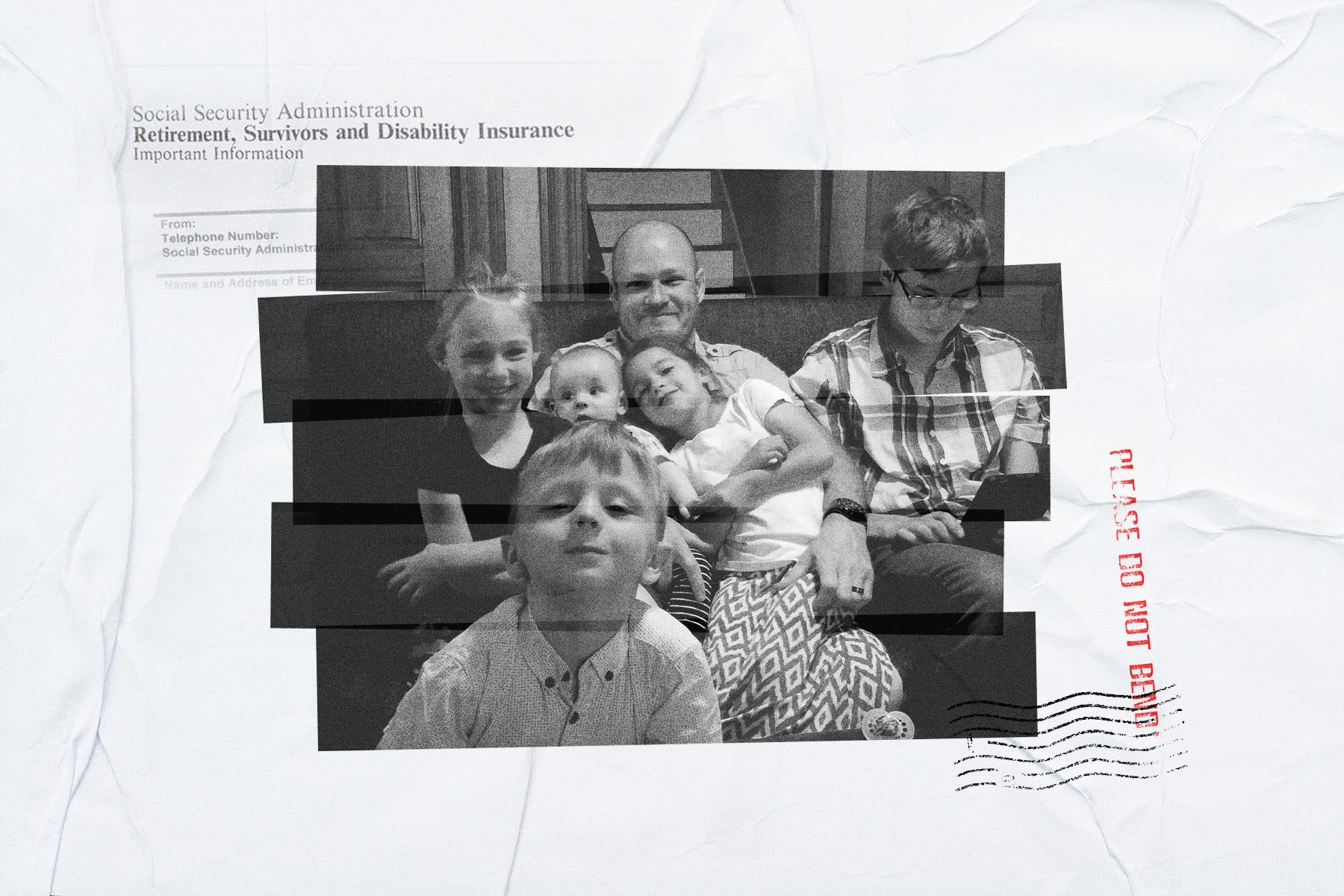

The day after her husband’s funeral, Rondell Gulick called Social Security. Now alone with their nine children, the stay-at-home mom faced what would become a months-long process of claiming the benefits she was counting on to keep her family afloat.

Gulick, like many people trying to access benefits, is at the mercy of phone calls. Across the country, Social Security Administration offices have been closed since the start of the pandemic and with nearly 900,000 additional deaths caused by coronavirus, there are thousands of people seeking Social Security survivors benefits, some who know little about the process. The majority of people seeking survivors benefits, by far, are women.

In December 2021, the most recent month of data, about 92 percent of those seeking young survivors benefits were women with one or more children, and about 96 percent of those seeking “aged widows benefits,” for those over the age of 60, were women.

If Gulick was retiring, she could apply online for those benefits. But for assistance with any other Social Security benefits — including survivors benefits — and with most offices almost totally closed to in-person visits, all she can do is call.

Applications that could be completed in one in-person visit in a normal year are taking weeks and even months to complete.

Gulick has spent hours and hours on the phone in the weeks after her husband’s death to try to get the benefits most of her children qualify for. Her husband’s income as a corrections officer sustained their entire family, made up of five biological kids and four adopted children from the couple’s decade as foster parents. The average benefit is about $1,000 a month per child, but there is a cap for larger families and Gulick doesn’t yet know what that will mean for her.

Ben Gulick’s death was sudden: He was only 45 when he died January 2 from complications related to COVID-19. Donations from family and friends have helped, but they will keep them going for only so long.

“Dealing with so many hurdles on top of dealing with loss, while also trying to help nine children grieve this process” has been stressful, Gulick said. “I do not know what our future holds. I just don’t know.”

In a normal year, the process would have been fairly simple. Gulick could have gone to her local office with her husband’s original death certificates, the children’s original birth certificates, their adoption documents and, perhaps, her original marriage license and completed the process on the spot. But all she has been able to secure at her local office in Carson City, Michigan, is an appointment for March — and that, too, will have to be over the phone.

Many people have to provide documentation to receive benefits. Without an in-person option, applicants for Social Security benefits like disability benefits and survivors benefits — paid to those who have lost a spouse or to dependents — will sometimes be required to mail original copies of sensitive documents, which has led some people to delay applying, experts said. They also must rely on limited customer service help to get through an application, which is particularly difficult if a person’s first language isn’t English.

“Social Security is vitally important to women and LGBTQ+ people and people of color — those who have been discriminated against historically, and especially lower-income people,” said Nancy Altman, president of advocacy group Social Security Works. “It just compounds all the issues with the field offices closed.”

Structural inequities have led women to rely more on survivors benefits, said economist David Weaver, a former associate commissioner in Social Security’s Office of Research, Demonstration and Employment Support. Women have significantly lower lifetime earnings — about 80 percent that of men by the time they are 65, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. And, because they tend to live longer, they’re more likely to be seeking benefits that in most cases will be higher than those they can claim on their own.

But the barriers of the past two years have impacted how many people have been awarded benefits at all. Benefit awards under Social Security’s anti-poverty program, Supplemental Security Income, are down 27 percent from 2019 to 2021. Awards in Social Security’s insurance program, which includes benefits for survivors, retirees and workers with disabilities, are down about 7 percent in that time frame.

The numbers are up slightly from 2019 for widows and widowers and surviving children, by about 10 percent, but there are signs that not everyone was getting the help they needed. Because of COVID-19, the death rate rose by 17 percent from 2019 to 2020, and though death reports are still being tallied, 2021 is expected to have been even deadlier. That means the increase in awards hasn’t kept up with the increase in deaths, and numbers would probably have been much higher if the field offices hadn’t closed, Weaver said.

“The fact that the [overall] data fell, that tells you people are having trouble getting access,” Weaver said. “The deaths are highly concentrated among the populations that Social Security serves. Those deaths are creating widows and survivors.”

Inside the field offices, workers have been coming in on a rotation to go through tens of thousands of pieces of mail and scan documents, but the demand has increased as the pandemic has gone on, along with phone calls. According to a report from the agency’s Office of the Inspector General, only about 51 percent of phone calls to field offices and the national number were answered in fiscal year 2020.

“It was an unsustainable situation that continued to deteriorate as demand increased,” said Peggy Murphy, the district manager of the Great Falls, Montana, Social Security office, during a hearing before the Senate Committee on Finance in April.

Social Security initially planned to reopen offices at the start of the year, before a surge in cases and pushback from unions delayed that plan until the end of March. Darren Lutz, a spokesman for the agency, said the plan now is for most employees to return March 30 and for increased in-person service to resume without the requirement for an appointment in early April.

For some who have already gone through the process, that’s too late.

Brianna Berry, 31, only started to seek out survivors benefits after other widows told her she could apply. Her husband, Lewis, was one of the earliest and youngest deaths from COVID-19 in the state of Indiana. He died in April 2020 at age 37.

Berry spent a part of those early months after Lewis died on the phone trying to reach someone at Social Security. At first she didn’t know if she could go in person, or even who to call. She couldn’t find information on how to apply on the website or what she qualified for. When she found a number to call, she bounced around between different phone numbers and representatives until she was finally able to apply.

And after all of that back and forth, her final benefit: $255. Because of her age and income, Berry didn’t qualify for anything other than the one-time death benefit payment. (Only young widows who earn little to nothing can get a benefit for themself. For widows under 60, Social Security starts to deduct how much you receive for every $2 you earn above about $19,500.)

Berry and her husband were married for 17 months and didn’t have children. If she’d had children, their benefits would not be impacted by her income. The lack of guidance cost her time in an already difficult period in her life, something she could have resolved quickly if she’d been able to go to her local office.

“I was angry, because it was like my husband worked his whole life and when he’s gone I don’t get any support because we didn’t have children,” she said. “It was like my grief was less because I’m young.”

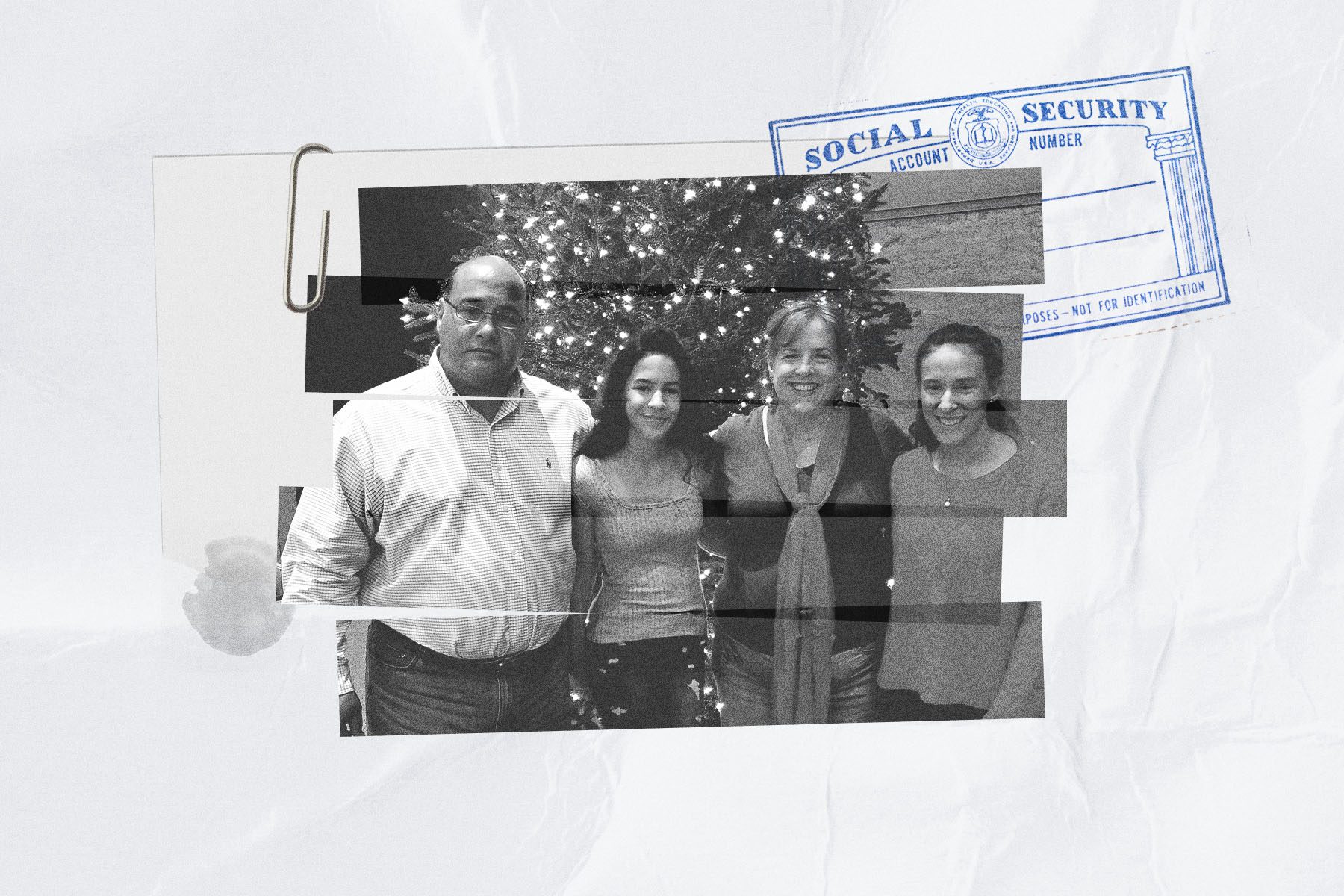

Jolene Reeves hasn’t been able to get through to Social Security. After half a dozen calls spending 45 minutes to more than an hour on hold, the Georgia resident only has a phone appointment scheduled for the end of March.

Reeves’ husband, Bennie, died from coronavirus complications in November, and she’s been working since December to apply for benefits for their two teenage daughters. Because she is 55, she won’t qualify for the enhanced benefits for “aged widows.”

Reeves, who works in billing for a maternal fetal medicine specialist, said the money isn’t critical for her like it may be for other people applying. What bothers her most is that the benefits that she’s owed are so difficult to obtain — and that the onus is on her to be persistent enough to keep calling.

“You go into a lot of places — even to get your nails done — they have the plexiglass between the person and [you]. Everyone’s figured it out but the government,” Reeves said.

The situation has stumped even attorneys who have been sought out to work as intermediaries with Social Security. John Whitelaw, the advocacy director for Delaware Community Legal Aid Society Inc., said he was part of a group that spent a year and a half working with Social Security to allow emergency in-person appointments. But even those are largely limited to people getting Social Security cards who can’t mail documents such as green cards.

Those applying for survivors and disability benefits get little relief, Whitelaw said.

“It’s not an eligibility problem, it really is a knowledge and access problem,” he said. “I don’t think it’s nefarious, and it’s not part of some plan, but I think it’s an unintended consequence of the public health precautions.”

For Nicholas Parr, an attorney at the Charlotte Center for Legal Advocacy, it has felt impossible to reach Social Security. One survivors’ case he’s been handling began in 2019 and has lasted through the entire pandemic. Social Security requested a birth certificate and, after a certified copy was sent, the agency said it never received it. Social Security later sent a message that the documents were received — but weeks later reached back out to ask for the birth certificate again.

That ping-pong alone spanned nine months. If the offices were open, Parr’s client could have provided the paperwork and finalized that piece of the application in one day.

“From my point of view, the fact that they’ve closed the office has made things incredibly difficult for anyone who has any interaction with Social Security and this has really been exacerbated by the fact that they’ve had some very serious issues with answering their phone calls,” Parr said. “The fact that they can’t go in and meet with someone or that they can’t reliably talk to someone by telephone is an incredibly serious barrier.”

The most significant challenges are for those who don’t have Internet access, a phone or easy access to mail, she said.

“Even during normal times, these individuals find it difficult to conduct business with SSA, but at least they could visit a field office. This is not a viable option so long as our lobbies remain closed to walk-in service,” said Murphy, the Social Security district manager, in her testimony.

Until offices begin to reopen in March and April, some field offices across the country have added drop boxes to allow people to drop off sensitive documents without worrying they’ll be lost in the mail. Long-term, however, the pandemic has proven the need for rapid technology updates at Social Security — and the outsized effect office closures can have on the ones who most need its services.

Adjusting for inflation, Social Security receives about 13 percent less in funding today than it did in 2010, despite the number of beneficiaries growing by 22 percent in that timeframe. President Joe Biden’s budget appropriates $14.2 billion to the agency, money that Murphy said could be used to improve processing for benefits, outreach to vulnerable populations and for IT system improvements.

Outreach, especially, is an area ripe for improvement. Weaver said Social Security could do a better job of collaborating with other agencies, like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to inform people who lose family to COVID-19 that they are eligible for benefits. Divorced widows and widowers, who could qualify for benefits depending on how long they were married, aren’t contacted by the agency when a former spouse dies. And fewer than half of surviving children get Social Security benefits, often because they never apply, Weaver said.

“Everybody thinks of it as a universal program — it’s universal for those over 65, but for children who have lost a parent, Social Security is not a universal program,” he said.

And even now with reopenings on the horizon, Social Security will have a new problem: demand.

Kathleen Romig, a senior policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities who is an expert in Social Security, said the agency will have to face the thousands of claimants who were unable to get through when its offices reopen.

“Advocates are saying it’s not enough simply to reopen — we also have this big backlog of people who weren’t served over the last two years,” she said.

Those people who have been waiting to apply have been doing so for a long time, and the backlog on the phone may now be taking place in Social Security lobbies.

“When Social Security does reopen,” she said, “it’s not going to look the same.”

Originally published by The 19th