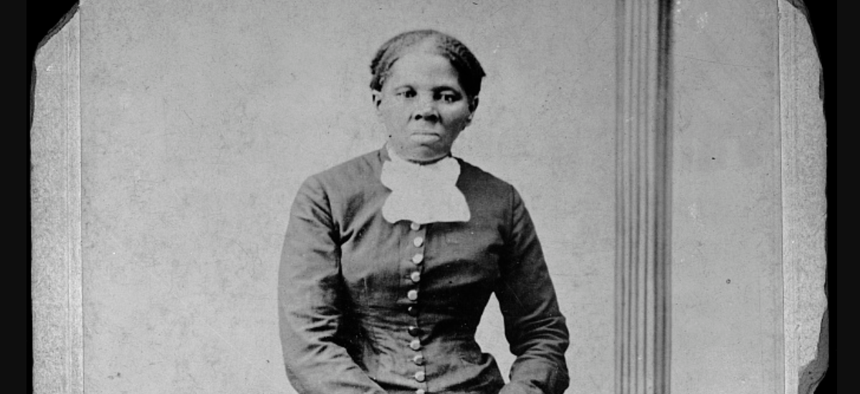

Harriet Tubman Library of Congress

Harriet Tubman’s Three-Decade Battle for a Federal Pension

She never did get a benefit based on her own heroic service to the Union Army.

On the night of June 2, 1863, Harriet Tubman commanded a unit of 150 Black soldiers in a daring raid up the Combahee River in South Carolina aimed at attacking a series of plantations and in the process freeing as many enslaved people as possible.

Tubman was the first woman to organize and lead a U.S. military operation, and it was phenomenally successful: About 750 people were freed, roughly 10 times the number that Tubman escorted to freedom on the Underground Railroad.

As the nation and the federal workforce celebrate the newest national holiday, Juneteenth, it’s worth remembering and recognizing the service and accomplishments of people like Harriet Tubman, and thinking about how they are compensated. That’s where the subject of federal retirement benefits comes in. Because Tubman fought for decades to get a federal pension, and never did get one based on her own heroic service to the United States.

That service began in 1861, when Massachusetts Gov. John Andrew recruited Tubman to help the Union Army. She joined an all-white force under Gen. Benjamin Butler at Fort Monroe, Virginia, where she cooked, washed clothes and served as a nurse. She later made her way to Port Royal, South Carolina, where she worked in a soldiers’ hospital.

With $100 in funding from the Secret Service, Tubman assembled a group of scouts who gathered intelligence that led to the planning of the Combahee River raid. Tubman herself also went on spying missions before the raid, relying on knowledge of the area gained during her trips on the Underground Railroad.

You might think that would be enough service to qualify for a pension as well as the thanks of a grateful nation, but you’d be wrong.

In 1865, after the war ended and Tubman returned home to Auburn, New York, she appealed to the federal government for compensation for her services to the military. She received $200. Then influential friends of Tubman’s began advocating for her to get a veterans’ pension.

That fight would continue for decades. In 1890, under a law passed by Congress, Tubman became eligible for a widow’s pension of $8 a month based on her husband’s service. Still, she and supporters such as William Henry Seward, President Lincoln’s secretary of State, pressed for the government to provide her with her own retirement benefit. In 1898, they filed an affidavit seeking a lump-sum payment of $1,800.

Members of the House of Representatives proposed to provide Tubman a $25 monthly pension based on her own service. Senators objected, however, saying the figure would set a precedent that other nurses would seek to match. In the end, Tubman, then nearly 80 years old, was granted an increase in her widow’s pension to $20 a month—34 years after the war ended, and with no recognition of her own service and accomplishments.

Think about that the next time you’re inclined to complain about the size of your retirement benefit or the time it took to process.